By Melik Kaylan

The great novel of the Caucasus "Ali And Nino” premiered as a movie recently in New York. Epic in scope and sweep, you might say it’s the Doctor Zhivago de nos jours. The famous story begins idyllically before World War 1 and ends tragically with the Russian Revolution, following a poignant romance set in Azerbaijan’s capital Baku and mountainous environs, a romance doomed by massive historical forces. The book’s love affair between a westernized Azerbaijani Muslim and a Christian Georgian princess has become a classic by now, a celebrated iteration of the ageless Romeo and Juliet quandary: youthful ardor puts to shame the caution and prejudice of older folk from opposing traditions but alas they’re proved right by the inevitable tragedy that unfolds.

What concerns us here is the crushing political backstory from which the young couple couldn’t free themselves – Moscow’s domination over Caucasus republics – a century old but in danger of resurfacing in our time. And affecting all of us.

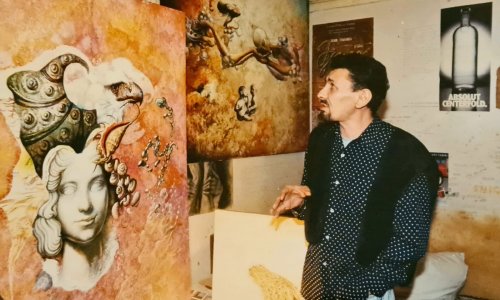

That said, everyone should see the movie for the sheer transporting beauty of landscapes and seasons, the drama of intense hope and loss amid the kind of exhilarating scenery that echoes grand tragedy. As the axiom has it, penmanship conveys stirring events through what it tells you, film depends on a showing you its meaning, via a sensory path of visual and musical cues. This one will lift your senses to a breathtaking pitch, not least by the exquisite internal décor common to the region, the turquoise-tiles and lush fabrics and dreamy light reflected off opulent textures. Director Asif Kapadia, oscar-laureated for his docudrama about Amy Winehouse, clearly has an inner grasp of what it feels like to inhabit such spaces, as no doubt does his award-winning Turkish cinematographer Gokhan Tiryaki. (The great British playwright Christopher Hampton wrote the script.) Here, then, is reason enough to see the film.

For our purposes, though, the main reason inheres in the film’s historical chronicle. Azerbaijan’s capital Baku had become an affluent oil capital in the early 1900s. The elite there, as in Istanbul and Tbilisi and indeed other trading cities further south such as Beirut and Alexandria, grew up in westernizing schools. Suspend, for a moment, any Edward Said-esque animosity you might feel toward ‘orientalism’ and the education of the east by the west. The only decent schools in existence then, those teaching modern topics using modern methods, science, math, engineering, medicine and the like were European or American. That is why Ali and Nino could bond across the religious and cultural divide. But with modern education came modern ideologies, countries yearning to be independent, that brought down the ancien regime of empires. Following the Russian revolution of 1917, Georgia established its first free republic soon to be quashed by Soviet troops in 1921. Southern neighbor Azerbaijan underwent the same rise and fall of high hopes in as few years. Ali brings disaster on himself when he stays to defend his country against invading Red Army soldiers despite Nino’s pleas that he escape to Paris with her.

At the Soviets’ collapse in 1991 both Georgia and Azerbaijan resumed their interrupted destiny – after 70 years. The first experiment had lasted three years. The post-Soviet one has endured thus far for twenty-five. But Moscow’s shadow over the region lengthens apace by stealthy increments. Often by increments not so stealthy such as Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 and the absorption of Georgian separatist zones into Moscow’s orbit. Azerbaijan hangs on staunchly for now but is surrounded by pro-Moscow regimes. With a new pro-Putin leader in the US, the pressure will only intensify. This is what we talk about when we talk about allying with the Kremlin, namely sacrificing the independence of entire countries from the Baltics to Asia. Because, with no help from the West, they’re easy prey. If the US cannot withstand the assault on its very democratic process via hacks and leaks, and the EU crumbles visibly from nationalist tremors, how on earth will Georgia or Azerbaijan resist Moscow’s predation?

Why should we care? Well, if it’s merely about realpolitik, there’s the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline. It provides non-Mideastern non-Russian oil to the world, notably to Europe. And indeed to Turkey, the West’s other big headache. Oil is a strategic weapon and Moscow’s re-extension of power over the Caucasus will extend its oil monopoly. There’s something else. It’s exactly in tucked away places like the Caucasus that the future of the world begins to unfold. The answer to the question, why should we care, is this: we didn’t care when Putin invaded Georgia and look where we are a mere eight years later.

www.forbes.com/sites/melikkaylan/2016/11/28/a-classic-love-story-now-a-movie-and-the-worlds-political-destiny/#75a4de5a2c35

www.ann.az

Follow us !