The strangest thing of all was that, in the end, it wasn't even that anxious.

If Andy Murray's first Wimbledon title had a giddy, dream-like quality, sealed with a tortuous final act, his second was sport as a peerless demonstration, a nerveless execution.

You could almost enjoy it. You could almost relax.

As his 6-4 7-6 (7-3) 7-6 (7-2) victory over a bemused Milos Raonic sank in, the 29-year-old buried his face in his towel and wept like a man overwhelmed by it all.

It was an image at odds with everything that had gone before. This was a fortnight of total control, a campaign almost without flaws, a final assault where every objective was taken exactly as planned.

Two sets lost in two weeks. Only two break points conceded in almost three hours. An opponent who had hit 137 aces in his previous six matches kept down to just eight in the entire contest.

If it appeared almost cold-blooded in its brilliance, the warm golden glow from this win will spread far beyond a celebratory Centre Court.

In an unparalleled era for British sport - a record-breaking haul from an unforgettable Olympics, a first Tour de France win and then two more, Ryder Cups won home and away, Lions series taken - Murray has now produced two of its most sacred days.

We can count ourselves blessed to have witnessed them. A men's singles title at Wimbledon was always the holy grail, impossible to even imagine for most of the 77 years. Men had lived and died without anyone getting close.

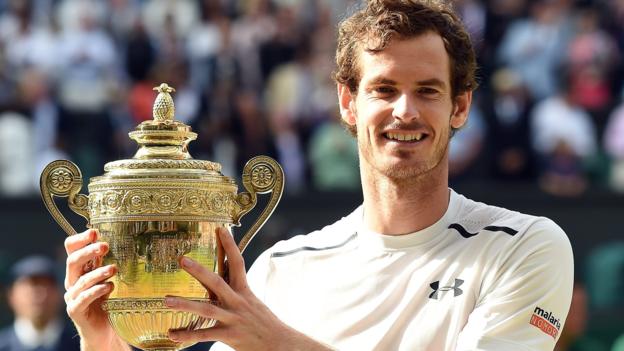

Now it has happened twice, and in such circumstances that only the perennially pessimistic could not imagine similar scenes on future summer days. Murray, hugging the old gold trophy so tightly to his chest that bolt-cutters could not have prised his arms away, looked a man with no intention of ever letting go.

Centre Court has not always felt this way for him. It was where he cried in defeat to Roger Federer in 2012, where he suffered death by tie-break to Andy Roddick in 2009, where he was overwhelmed by Rafael Nadal in successive semi-finals over the next two years. Even after the wonder of 2013 came quarter-final defeat Grigor Dimitrov and the perfection of Federer in the semi-final a year ago.

On Sunday it was once again his sun-kissed domain. And while 2013 may never be matched for emotional impact, for its first man back on the moon wonder, for its stop-the-clocks shock, this second win is arguably a greater achievement still.

Since the defeat of Novak Djokovic three years ago there has been surgery on his back and a brutal dissection of his game in the three Grand Slam finals where the two have met again. Murray appeared doomed to be the most gifted of stooges, a brilliant player denied his rightful rewards by the misfortune of playing all his 10 Slam finals against two of the greatest talents in history.

Djokovic's recent supremacy has cowed other men, left other contenders wondering what else they could possibly do.

Murray, at a stage of his career where he is financially comfortable and reputationally secure, has instead pushed harder. A stronger second serve, a faster forehand. A greater consistency, a renewed resolve.

Each of those and more came together on Sunday afternoon. It is unfair to call Raonic a tennis robot, for he too has added sweet elements to his game, displayed more than just a car-crusher serve in fighting through to his first Grand Slam final.

There is romance too in his back-story, if not the same saga that Murray has created: the immigrant kid with non-sporting parents, the outsider who had to train at 6am and 11pm when coming through because it was the only time his family could afford the practice courts.

On Sunday Murray ripped out his circuit-boards. A serve that has been unstoppable all tournament was returned with impossible ease. A volleying game that took him past Federer on Friday was first damaged then dismantled. A man who has moved better in this fortnight than ever before was left looking heavy-legged and unhappy.

Murray had broken him in the seventh game of the first set when the Canadian put a simple volley into the net. But it was in a game Raonic eventually won that perversely produced the moment that best summed up the match: 4-3 in the second set, a hammering 147 mph serve, the second fastest in championship history, returned by Murray as if hit in slow-motion, followed up by a backhand pass that reduced his opponent to audience member, to powerless bystander.

It was one of so many backhand winners, one of so many brilliant returns, that even had Djokovic been across the net once again you sensed the result may have been the same.

Raonic and Murray had played five tie-breaks before this final. Raonic had won four of them. In the two here, Murray was 5-0 up before the younger man could blink, his defence outstanding, his shot selection perfect.

Gone was the introverted, sometimes disconsolate figure who can appear at war with himself when things turn bad. There was shouting, and there were pumping fists, but all of it channelling inner warrior rather than teenager, a man in maturity assured of everything at his feet.

Throughout it all, Ivan Lendl, his totem of a coach, sat watching with all the obvious passion of a Easter Island monolith. Then, because it was that sort of day, he too cracked, tears in the eyes as his charge raised his arms to the south London skies.

Because that is what Murray has brought to his faithful watchers: torment at times, and sometimes disappointment and frustration, but also great pleasure in his artistry and achievements. And on days like this, days most of us could once never imagine, a happiness that will remain long after the celebrations and eulogies have died away.

(BBC)

www.ann.az

Follow us !