Trapped between Turkey in the south and Russia to the north, the small countries of the Caucasus - Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan - find themselves in markedly different positions over the escalation of tensions between Turkey and Russia after the downing of a Russian jetfighter by Turkey on November 24.

Armenia, which does not have economic ties with either Turkey or its ally Azerbaijan, is the only country which has unswervingly supported Russia over the incident. Moreover, its agriculture minister also sees Russia's sanctions against Turkey as an opportunity for Armenia to increase its exports of produce to Russia.

Meanwhile, Georgia and Azerbaijan maintain significant commercial ties with both of their larger neigbours, and are stuck between a rock and a hard place.

All three countries stand to benefit from the spat between Russia and Turkey in some areas, such as potentially higher numbers of inbound Russian tourists or opportunities to export more agricultural goods to Russia and, possibly, some textiles.

However, all three countries also share a high level of vulnerability to external shocks, because of their small size and the importance of foreign trade and investment to their economies. If Russia's economic sanctions on Turkey signigicantly affect growth of the Russian and/or Turkish economies, then all three Caucasian economies will suffer indirectly as a result.

Even Armenia might find Russian sanctions to be a curse; no matter how much Yerevan increases its exports of fruit and vegetables to Moscow, no amount of produce will offset the economic impact of decreasing gas trade between Russia and Turkey on regional economies.

Armenia

Yerevan essentially operates as an extension of Russian economic and political interests in the Caucasus. The ties between the two countries are so strong, that Demetrios Efstathiou, ICBC Standard Bank's head of trading strategy, noted in his trip notes on Armenia published on November 25 that "Armenia is not an oil exporter. Yet its economy depends so heavily on oil-exporting Russia, that treating it as one makes sense."

A fourth of Armenia's foreign trade between January and September - $871.5mn out of $3.5bn, was exchanged with Russia. Meanwhile, remittances, which are equivalent to about 20% of Armenia's GDP, according to Efstathiou, come almost entirely from Russia. Russia's largest companies - Rosneft, Gazprom, Mars, Rusal and banks VTB and VEB have monopolised entire sectors of the Armenian economy - energy, consumer electronics, aluminium and finance.

But Russia's support for Armenia in its conflict with Azerbaijan over the breakaway region of Nagorno-Karabakh is probably the single most important factor that ties Yerevan to the Kremlin. Without Russian military support as part of the Moscow-led CIS Collective Security Treat Organisation, Armenia would face certain defeat in another standoff with Baku. Yerevan became even more dependent on Moscow in January, when it joined the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), a Russia-led free trade bloc that aims to counterbalance the EU's importance in Central and Eastern Europe with a Moscow-led union further east.

Armenia's membership of the EEU has not been a bed of roses so far, mainly because of the economic recession in Russia this year. Thus, its foreign trade dropped by 20% y/y in January-September and the central bank expects remittances to decline by 25% this year compared to 2014. Should tensions with Turkey escalate to the point where the Russian economy is heavily affected, Armenia will suffer echoes of that development.

The Armenian agriculture sector is, however, set to benefit from the sanctions on Turkey. The country's agricultural exports have already increased by 68% this year, and Russia imported a staggering 84% of them. And Yerevan will not stop there, for, according to Agriculture Minister Sergo Karapetyan, it is seeking to further increase exports in the following months.

"As we know, Russia has decided to limit the imports of Turkish agricultural products. This is creating new opportunities for Armenian producers in terms of increasing the volume of exports to the Russian market. Because of upcoming New Year holidays the demand for the products is also increasing, and this is why we need to develop short- and long-term programs to increase production and exports," Karapetyan said in a press release.

Azerbaijan

Meanwhile, Azerbaijan's position is more delicate, because the country maintains close commercial relations with both Russia and Turkey. "Out of all the countries in the region, the prospect of a Russo-Turkish scrap raises the most concerns for the Aliyev leadership in Azerbaijan," Nomura International's Tim Ash noted in an analysis released on November 27.

The administration of Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev has been very close to Ankara, but has treaded carefully with Russia, especially after the latter's invasion of Crimea two years ago. Despite their shared Soviet past and cultural similarities, Azerbaijan and Russia have a historical distrust which stems from Russia's support of Armenia in the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh.

"Azerbaijan has been moving closer to Turkey - trade, energy, culture, for the period since 1991, but since the crisis in Ukraine, and Russia's new found assertiveness in the near abroad in terms of foreign/security policy, Azerbaijan has been trying to play both sides, trying to reach back out to Russia to assure that it is more neutral in the wider Russia/Western stand-off in the region," Ash notes.

That might perhaps explain why Baku's response to the row between Ankara and Moscow has been to express sorrow and say it is willing to help placate tensions. On November 27, Aliyev met Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu and vowed to make efforts to reduce tensions between the two countries, although he did not specify how he would moderate the conflict.

"Any further weakening in the Russian/Turkish economies would be a disaster for the Azeri economy", Ash writes, "as it is already suffering badly from the collapse in oil/energy prices, and this has seen pressure on the manat, and the rapid depletion of energy resources. It [Azerbaijan] faces depletion of oil reserves and the need for large-scale investment in gas production/pipelines where the potential is huge. But any threat of a Russia/Turkey spat could see such foreign direct investment (FDI) dry up pretty quickly."

Ash might be somewhat overstating the importance of Russian and Turkish investments in Azerbaijan's energy sector. Russia and Turkey are indeed leading investors in the non-oil economy in Azerbaijan, and accounted for 6.8% and 14.1% of the $4.26bn in incoming FDI between January-August. However, the main investors in Azerbaijan's energy sector remain the UK, Norway and Iran, while the main export destinations for Azerbaijan's oil and gas are European markets - Italy, Germany and France, as well as Israel and Indonesia. So Russian and Turkish investment in Azerbaijan's energy sector, which is made mostly through Lukoil and TPAO, is not such a big factor.

Rather, Russian and Turkish companies are some of the largest investors in the non-oil economy in Azerbaijan, and operate businesses in hospitality, trade, construction, finance and tourism, so a further decline in their economies will impact on Azerbaijan's much-touted economic diversification agenda.

Meanwhile, the agricultural sector is poised to benefit from a reduction in Russian imports of Turkish goods. Just like Armenia, Azerbaijan has been eyeing higher trade with Russia, particularly in agricultural products, long before tensions with Turkey began, and could boost its exports of fresh and processed produce.The fact that the Russian Agriculture Minister Alexander Tkachev mentioned Azerbaijan as a potential source of tomatoes to replace Turkish ones is an indication that Azerbaijani food exports to Russia might indeed benefit as a result of the latest development.

An important way in which Azerbaijan could be affected by a potential slowdown in the Turkish economy is through its sizeable business interests in Turkey. Azerbaijan, through its national oil company Socar, was among the top five foreign investors in Turkey in the first quarter of 2015.

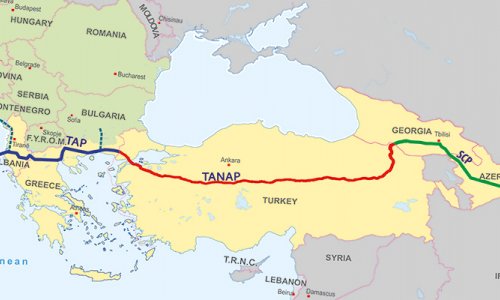

Socar owns a 51% is one of the largest refineries in Turkey - the Petkim refinery; its own refinery called the Star refinery; and a 58% share in the Trans Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP), a project aiming to deliver Azerbaijani gas to Turkey and further to Europe. TANAP, as well as a railway connection between Baku, Tbilisi and Kars in Turkey, have already been affected by the instability in Turkey's southeastern region, which forced works to be temporarily stalled or delayed. Added economic woes in Turkey could only aggravate the problem and, possibly, affect other Azerbaijani interests there.

The same could be argued for Russia, albeit to a smaller extent. Azerbaijani companies and the state itself through sovereign wealth fund Sofaz have interests in Russia that range from canning factories to carpet businesses and to shares in Russia's VTB Bank, so any further slowdown in the Russian economy is bound to adversely affect Azerbaijani interests there.

Georgia

Georgia's position is somewhere between Armenia's and Azerbaijan's. On the one hand, there has been deep distrust between Tbilisi and Moscow ever since Russia invaded Georgia in August 2008 to wage a five-day war over the breakaway region of South Ossetia. In that regard, Georgia's relations with Turkey are much closer than its relations with Russia, despite the fact that Georgia and Turkey do not share the same cultural background - religion, Turkic origin, language – that Azerbaijan and Turkey do, and that Georgia and Russia do share a common past and religion.

Despite the deep distrust between Tbilisi and Moscow, the reality is that Russia is an important trading partner for Georgia, slightly more important than Turkey. For instance, in 2014, Russia bought 9.6% of Georgia's exports, while Turkey ranked as the fourth export destination for Georgian products with 8.4% of the total exports. That said, unlike Turkey and Armenia, Georgia does not depend on Russia for energy imports - over 90% of its gas comes from Azerbaijan, so in that regard, Georgia could survive without Russian commerce, unlike Armenia, but its economy would take a hit.

Nowadays, thousands of jobs in Georgia in sectors like tourism and agribusiness, particularly wine making, depend on exports to Russia. Russia has previously enacted economic sanctions on Georgia between 2008 and 2012, so the country has been in Turkey's place and knows the economic harm that sanctions can do. Ever since the sanctions were lifted in 2012, Georgia has played a skilful act and managed to increase its exports to its northern giant, while signing free trade and an association accords with the EU. And while this year's economic recession in Russia has affected trade with and remittances to Georgia, the country is unlikely to want to risk losing the Russian market again.

"Exports to Russia are very important to the stability of the national currency, the lari, which depreciated by 35% in the last year," economist Giorgi Khukhashvili, former adviser to the Georgian prime minister, said in an August interview. Since 2012, the Kremlin has occasionally used its consumer protection agency Rospotrebnadzor to threaten bans on Georgian products when Georgia got a little too cosy with Nato or the EU for Russia's liking. And for all the advances the Caucasian country has made in enhancing its trade with the EU and, more recently, with China, the reality is that the country still needs Russia.

Therefore, much as they dislike Russia and the Putin administration deep down, neither Azerbaijan nor Georgia can afford to take a pro-Turkey stance without jeopardising the significant trade and investment they exchange with Russia. Tiny Armenia is poised to remain in Russia's shadow for the foreseeable future, so its position is both predictable and easy, although potentially disastrous if the Russian economy sinks further into recession as a result of the tensions with Turkey.

(intellinews.com)

www.ann.az

Follow us !