Nasimi Aghayev, Consul General of the Republic of Azerbaijan, is a remarkably patient envoy.

He admits that he’s grown accustomed to the blank stares with which many Americans and others often greet him when he tells them that he represents Azerbaijan, a mostly Muslim, former Soviet republic in the Caucasus Mountains of Central Asia that is now an independent nation.

Often, the affable and articulate consul general told the Intermountain Jewish News in an interview last week, people not only don’t know where Azerbaijan is, they don’t know what it is.

Even those who are better informed — who know something, for example, of the bloody Nagorno-Karabakh War in the late 80s and early 90s during which Azerbaijan lost a significant piece of its territory to neighboring Armenia and ethnic Armenian militants — often know very little else about Azerbaijan.

That’s OK with Aghayev. Informing Americans about his homeland, its history, culture, geography, economy and future aspirations is a major part of his job.

That’s OK with Aghayev. Informing Americans about his homeland, its history, culture, geography, economy and future aspirations is a major part of his job.

Founded in 1991, Azerbaijan is a relatively new nation, he explains. It is a long way from North America, in a region in which, until recently, the US has never had a major presence, and it has never had a substantial immigrant population in the US.

Not to mention, he adds with a wry smile, the name Azerbaijan is rather difficult for Americans to pronounce.

Based in Los Angeles — in the same building housing Israel’s consulate, he notes significantly — Aghayev is responsible for 13 Western states, including Colorado.

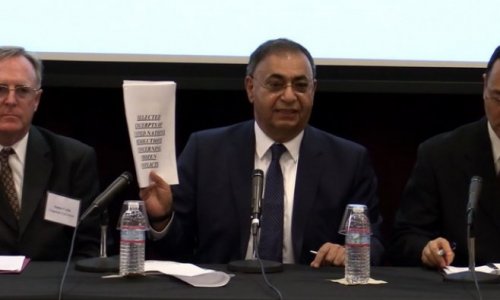

He came to Denver to meet with Colorado state legislators and to be honored by the Colorado Senate for his work in promoting ties and friendship between Colorado and Azerbaijan.

He also hoped to meet potential business partners here, and to make contacts for trade, education and other sorts of exchanges.

He asked for a meeting with the IJN, Aghayev added, because he wants to establish and expand ties with Colorado’s Jewish community.

Having a positive relationship with American Jews, he says, is very important to Azerbaijan, as are its strong political, economic, cultural and military ties with the State of Israel.

Azerbaijanis, Aghayev says, consider their close ties to Jews an integral part of their heritage, something of which they are clearly proud.

‘We’re trying to set a good example and show the whole world that it’s possible for Muslims, Jews and Christians to live together in peace and harmony. We have a strong societal foundation for that.”

Some 30,000 to 35,000 Jews live in Azerbaijan today, Aghayev says, a few of them descending from European Ashkenazi communities, but most of them descendants of the so-called Mountain Jews (also known as Caucasus or Kavkazi Jews) who have lived in the greater Caucasian region for a very long time.

"It’s a very vibrant community,” he says, "an ancient community that has been there over 2,000 years.”

Ethnically, culturally and religiously distinct from the Georgian and Bukharan Jewish communities, which are based in different parts of Caucasia, the Mountain Jews originated in ancient Persia. To this day they speak a distinctive hybrid of ancient Farsi and Hebrew.

Many of the Mountain Jews have traditionally lived in the Quba region, in a town whose Azeri name equated with "Jewish town,” since this was a place where Azerbaijani rulers guaranteed Jews rights of residency.

In the 20th century, after the Soviet Union absorbed Azerbaijan, the town’s name was changed to "Red town,” Aghayev says.

For some 16 centuries, Azerbaijani Jews have resided in an overwhelmingly Muslim region. Today, Aghayev says, Azerbaijan is 92% Muslim, with small Christian, Hindu and other minorities. Jews constitute only some .10% of the current population.

Yet anti-Semitism — and religious discrimination in general — is virtually unknown in Azerbaijan, he emphasizes.

"Through all these centuries, Jews have lived in Azerbaijan amidst Muslim Azerbaijanis without any persecution, any pogroms, any discrimination.”

International studies on anti-Semitism back up that claim, with most citing very low rates of anti-Semitism in Azerbaijan.

There are Islamic political activists, however, who routinely express anti-Semitic and anti-Christian sentiments, and Azerbaijani authorities have more than once arrested terrorist cells, backed by both Iranian and Arab sources, that were likely planning attacks against Jewish or Israeli targets.

Aghayev stresses that modern Azerbaijan is led by a government committed to democratic and secular values.

"The government is separate from religion but it respects all religious freedoms,” he says. "For us, all religions are equal and they all receive the same amount of attention from the government. So we are building mosques, synagogues, churches.”

In 2011, for example, the central government built a new synagogue for the Jewish community in the capital of Baku. More recently, Aghayev played an instrumental role in obtaining a sefer Torah for the congregation, asking Rabbi David Wolpe of Temple Sinai in Los Angeles to help raise funds from his congregants.

This week, Aghayev presided over a ceremony in Los Angeles in which the Torah was presented to members of the Baku congregation.

Speaking a few days before its occurrence, he said, "It will be a milestone event in the history of the Azerbaijani Jewish-American relationship.”

LONG AGO, the region constituting modern Azerbaijan — a mostly mountainous land with spectacular alpine views to rival those of Colorado — was traversed by the legendary Silk Road, a critical trade route of the ancient world.

Aghayev contends that the region’s exposure to so many traveling traders from distant lands cultivated its sense of acceptance.

Although that exposure had its downsides, he concedes — "we’ve had many uninvited guests as well” — Azerbaijan "has been a meeting place of civilizations, cultures and religions.

"The Silk Road helped the development of the country. It also helped develop this culture of respecting and accepting each other.”

The attitude is not well-defined by the word tolerance, Aghayev adds, since tolerance implies a negative — that somebody needs to be "tolerated” despite their differences.

"In Azerbaijan, it transcends tolerance. It’s mutual acceptance, mutual respect and celebration of each other’s culture. It’s a good example for many others, especially in these turbulent times.”

Modern Azerbaijan is doing its best to maintain that historical tradition, aspiring, in Aghayev’s words, "to build good relations with all the countries in the world.”

It has "normal relations” with most of its neighbors, including Russia and Iran, and boasts "an excellent relationship” with the US and Europe.

It has opened up energy development to such Western energy giants as Amoco, BP and Total, and has a pipeline transferring oil through Georgia and Turkey to the Mediterranean Sea.

Much of that oil ends up in Israel, with which Azerbaijan also has strong ties.

Some 50% of Israel’s petroleum comes from Azerbaijan, Aghayev says. Israel, in turn, supplies Azerbaijan with much of its advanced armaments.

The two nations do some $4 billion in annual trade, making Azerbaijan Israel’s largest trading partner from Central Asia in the post-Soviet era.

According to a 2014 study by the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies of Bar-Ilan University:

"In the foreseeable future, it is likely that Azerbaijani-Israeli relations will only increase in areas such as scientific cooperation, information technology, medicine, water purification, agriculture and cultural exchanges.”

"We’re natural allies,” Aghayev says of Azerbaijan and Israel.

"There are similarities between Azerbaijan and Israel. We are both islands of stability in difficult regions.”

HIS COUNTRY’S relations with Israel are close and mutually beneficial, he says, but an atmosphere of realpolitik does hover over their ties.

While Israel was one of the first nations to formally recognize the new state of Azerbaijan, opening an embassy in Baku in 1993, Azerbaijan has yet to open an embassy in Jerusalem, citing its "complicated geopolitical situation.”

That translates into the difficulties such recognition might cause with Azerbaijan’s Muslim trading partners, most of which, including Iran and Turkey, are hostile to Israel.

That’s also why Azerbaijan treads very carefully when commenting on such Middle Eastern issues as the Israel-Palestinian conflict. When asked about it, Aghayev replied in a cautious tone.

"Our position is that a two-state solution is the best one,” he says.

"We want the Palestinians and Israelis to find a common language. We hope that whenever they relaunch peace negotiations that they will finally yield some results.”

Despite such carefully calculated neutrality, and the overall diplomatic high-wire that Azerbaijan has chosen to walk, Aghayev says his country is very serious about its desire to maintain close ties to Israel.

"There is a common perception that Israel is at war with the Muslim world but one example — Azerbaijan — shows that to be wrong. Our bilateral relationship shows that it’s possible.

"We’re always very honest in our relations with Israel and with the Muslim and Arab countries. The largest organization in the Muslim world is the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, which has 57 members. Last year they appointed an Azerbaijani diplomat to represent the organization in Brussels, in the European Union.

"It shows the trust they place in Azerbaijan as a bridge-builder.”

That position, Aghayev says, says a lot about how Azerbaijan sees itself, and its international role, in the 21st century.

"We try to be honest, not giving the perception that we doing something behind the door,” he says. "So we are friends with Israel but we also have great relationships with many Muslim countries.

"And it’s working.”

IF THERE is a potential sore spot in relations between Jews and Azerbaijanis, it likely lies in disagreements over Armenia.

Azerbaijanis’ primary perception of Armenians is as invaders, the instigators of the early 1990s conflict that resulted in tens of thousands of deaths, more than a million displaced Azerbaijanis and the loss of land that Azerbaijan still considers its sovereign territory, primarily the Nagorno-Karabakh region.

Many Jews see Armenians as victims, specifically of persecution at Turkish hands in WW I, during a forced relocation effort in which as many as one to 1.5 million Armenians were murdered.

The more recent incident, involving Azerbaijan, is described by Aghayev as a "huge human tragedy” resulting from Armenia’s "war of aggression and occupation.”

Aghayev is less dramatic in describing the earlier incident, involving the Turkish Ottoman Empire, which he says resulted in "human suffering” but did not constitute genocide.

Genocide, Aghayev says, implies a deliberate and systematic effort "to eradicate a group of people because of their ethnicity or race.”

The Nazi Holocaust against the Jews was genocide, he says, but Turkish action against the Armenians in 1915, which took place during a wartime relocation, was not.

Partisans on both sides of the debate have long argued, and are still arguing, over this semantic distinction, although most historians place themselves firmly on the side that contends that the Ottoman actions amounted to genocide.

Ever the diplomat, Aghayev hopes to find a neutral zone between the two sides, even while acknowledging Azerbaijan’s enmity with Armenia and its close cultural, ethnic and religious ties with Turkey.

Azerbaijan supports the idea of creating "a joint historic commission,” including Armenia, Turkey and other international participants, to investigate what really happened.

"One side is saying it was a genocide, the other says it was not a genocide and they will never agree,” Aghayev says.

"There are two options. Either you stay enemies forever or you try to find a common language.”

(Intermountain Jewish News)

ANN.Az

Follow us !