As the late afternoon sunshine casts down through the trees, dappling the Cotswold stone, Sir John Graham comes out to greet me.

It makes his stories of bloodied scarves waved as trophies and tanks in the streets seem unreal.

But Sir John is a witness to the history of Britain's troubled relations with Iran.

He took up the post of British ambassador in Tehran just as the revolution in January 1979 reached its climax - less terrifying, he says, than thrilling.

"It was fascinating to watch a revolution developing, almost as if it has a life of its own. There was nobody really in charge," he says.

Sir John's is an important voice to hear as Britain and Iran try - not for the first time - to restore relations abruptly severed in the aftermath of the revolution.

He tells me he became a Middle East specialist by accident but it shaped his career, with postings in Bahrain, Kuwait, Jordan, Libya, and in the mid-70s as ambassador to Iraq.

Mutual distrust

You could almost describe Mehrdad Khonsari as Sir John Graham's alter ego.

Coming from a distinguished Iranian family - an ancestor was prime minister 200 years ago - he served in Iran's UN mission before being sent to London. He was press attache there at the time of the revolution.

He says that since then distrust between the two countries has become a habit, but adds: "Where there has been distrust, there has also been great affinity."

That distrust helps to explain how during the past 30-odd years relations have improved and then deteriorated again, for example over the fatwa issued against novelist Salman Rushdie and more recently when the British embassy was sacked by a mob in 2011.

The two countries have still not agreed to exchange ambassadors, and there is as yet no consular service in Tehran, so Iranians hoping to apply for visas to visit the UK still have to go through a third country.

Mr Khonsari tells me that the reopening of the two countries' embassies on Sunday may have been accelerated.

"It was pushed forward, perhaps, given the fact that many European countries are trying to enhance their ties with Tehran, especially for economic reasons".

This week, Philip Hammond became the first UK foreign secretary to visit Iran since 2003.

And he brought with him a group of business people.

The British government will be well aware that countries such as Germany already have something of a competitive edge in trade with Iran.

Still, language and longstanding cultural ties will help British companies in what Mr Khonsari calls the largest untouched market in the world.

It was Mr Hammond's predecessor William Hague who began the process of restoring diplomatic relations, long before the recent agreement over Iran's nuclear programme.

Yet the nuclear question hovers in the background.

Opposition from Israel, Saudi Arabia and many in the US Congress means there is no guarantee that improved relations will be cemented.

The sceptics point out that although President Hassan Rouhani may be keen for closer ties, the country's Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, is guardian of the Islamic revolution and in the past has been hostile to the West.

Changing interests

Mehrdad Khonsari, a political exile, is no apologist for the regime - but he says other countries need to recognise that Iran's strategic interests have changed.

"That nuclear deal could not have been reached minus the support of the supreme leader, so what you have to bear in mind is that there has been a major shift in his position," he says.

"The fact is the regime cannot continue to maintain control and stability within the country unless it moves in a different direction, and restoring ties with Britain ties in with that overall picture of trying to move in a completely different direction to save the country."

Sir John agrees. As a retired diplomat, it is no surprise he prefers jaw-jaw to war-war.

Still, one anecdote he tells me might give some people cause to reflect on the different approach that a theocratic regime, as opposed to a secular one, may adopt.

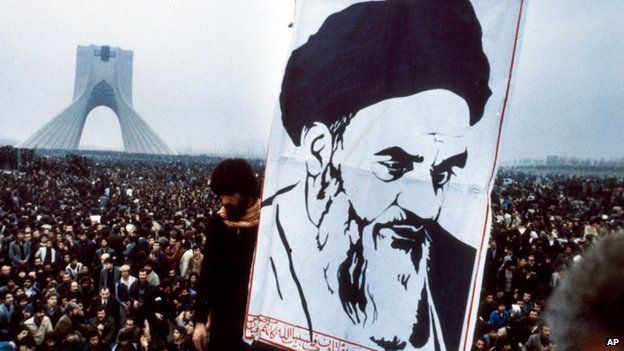

The revolution began as a secular revolt, but eventually it was the supporters of Ayatollah Khomeini who gained control.

1979 revolution:

Before the revolution, Iran was ruled autocratically by Shah Reza Pahlavi.

During the 1970s, the gap between Iran's rich and poor grew, fuelling dissent and resentment.

Opposition voices rallied round Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a Shia cleric living in exile in Paris, who promised social and economic reform and a return to traditional religious values.

Violent anti-Shah protests swept Iran in the late 70s, and the economy was crippled by a wave of general strikes.

The shah left Tehran in January 1979, never to return.

On 1 February 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini made a dramatic return from exile.

As political and social instability increased, Prime Minister Shahpur Bakhtiar resigned.

Two months later, Ayatollah Khomeini won a landslide victory in a national referendum.

He declared an Islamic republic, and was appointed Iran's political and religious leader for life.

Britain had no established links with the new rulers.

However, in April 1980, Sir John eventually gained an audience with Mohammad Beheshti, the chairman of the Council of the Revolution.

This was several months after US embassy staff had been seized, and they were still being held as hostages.

"He was generally thought to be the eminence grise," Sir John tells me, "and I tried to bring home to him the outrage on the part of the US government over what they were doing to their embassy and their staff.

"He shrugged, and he said, 'Well, if we have a third world war, we will go to heaven.'"

(BBC)

www.ann.az

Follow us !