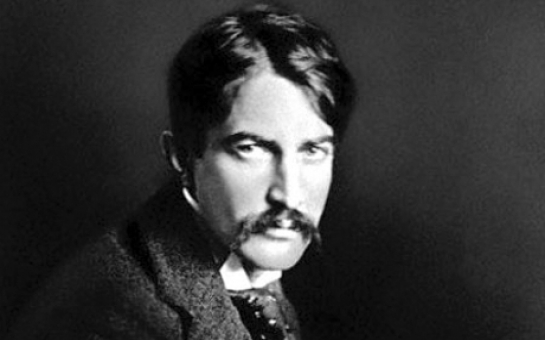

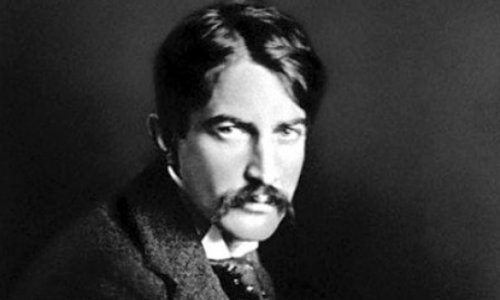

Stephen Crane (1871-1900) was born in 1871 in Newark, New Jersey. He was educated at Lafayette College and Syracuse University. In 1891, he got a job as a freelance reporter, writing articles about the slums of New York. Without steady work as a reporter, Crane, himself, was a poor man and lived in The Bowery, New York's worst slum.

This firsthand experience of poverty gave Crane the material he needed for his first novel, Maggie, a Girl of the Streets. It was a tragic story about a young prostitute who commits suicide. Crane used what little money he had to publish the book in 1893, using the pen-name Johnston Smith. Although it was not a commercially successful novel, the book received excellent critical reviews.

In 1895, Crane published his second novel, The Red Badge of Courage. It was a powerful and realistic psychological portrait of a young soldier fighting in the American Civil War. This novel brought Crane international recognition as a great novelist. He was one of the first American writers to work in the style known as Naturalism.

Naturalism portrayed characters who were not in total control of their lives, but rather, were strongly affected by natural forces. These forces could be the internal emotions or personality conflicts of the characters themselves, or they could be external elements like the stormy sea in The Open Boat, or social situations, such as war in The Red Badge of Courage.

Although Crane had never been a soldier himself, he worked as a war correspondent for several American and foreign newspapers. He reported on the war between Greece and Turkey in 1897, as well as on the Spanish-American War, fought between the United States and Spain, in Cuba and the Philippines in 1898.

Just before the Spanish-American war broke out, Crane was shipwrecked while on an expedition to Cuba. This experience is the basis of The Open Boat. The character referred to in the story as the correspondent is most likely Crane himself. Sadly, Crane developed tuberculosis as a result of his weakened condition after the shipwreck. He died in 1900 at the age of 28.

SHORT STORY: SHAME

"Don't come in here botherin' me," said the cook, intolerantly. "What

with your mother bein' away on a visit, an' your fathercomin' home soon to

lunch, I have enough on my mind -- and thatwithout bein' bothered with you.

The kitchen is no placefor little boys, anyhow. Run away, and don't be

interferin' withmy work." She frowned and made a grand pretence of being

deep inherculean labors; but Jimmie did not run away.

"Now -- they're goin' to have a picnic," he said, half audibly.

"What?"

"Now -- they're goin' to have a picnic."

"Who's goin' to have a picnic?" demanded the cook, loudly. Her accent

could have led one to suppose that if the projectors didnot turn out to be

the proper parties, she immediately would forbidthis picnic.

Jimmie looked at her with more hopefulness. After twentyminutes of futile

skirmishing, he had at least succeeded inintroducing the subject. To her

question he answered, eagerly:

"Oh, everybody! Lots and lots of boys and girls. Everybody."

"Who's everybody?"

According to custom, Jimmie began to singsong through his nosein a quite

indescribable fashion an enumeration of the prospectivepicnickers: "Willie

Dalzel an' Dan Earl an' Ella Earl an' WolcottMargate an' Reeves Margate an'

Minnie Phelps an' -- oh -- lots moregirls an' -- everybody. An' their

mothers an' big sisters too." Then he announced a new bit of information:

"They're goin' to havea picnic."

"Well, let them," said the cook, blandly.

Jimmie fidgeted for a time in silence. At last he murmured,"I -- now -- I

thought maybe you'd let me go."

The cook turned from her work with an air of irritation andamazement that

Jimmie should still be in the kitchen. "Who'sstoppin' you?" she asked,

sharply. "I ain't stoppin' you, am I?"

"No," admitted Jimmie, in a low voice.

"Well, why don't you go, then? Nobody's stoppin' you."

"But," said Jimmie, "I -- you -- now -- each feller has got to

takesomethin' to eat with 'm."

"Oh ho!" cried the cook, triumphantly. "So that's it, is it? So that's

what you've been shyin' round here fer, eh? Well, youmay as well take

yourself off without more words. What with yourmother bein' away on a visit,

an' your father comin' home soon tohis lunch, I have enough on my mind --

an' that without beingbothered with you."

Jimmie made no reply, but moved in grief toward the door. Thecook

continued: "Some people in this house seem to think there's'bout a thousand

cooks in this kitchen. Where I used to workb'fore, there was some reason in

'em. I ain't a horse. A picnic!"

Jimmie said nothing, but he loitered.

"Seems as if I had enough to do, without havin' youcome round talkin'

about picnics. Nobody ever seems to think ofthe work I have to do. Nobody

ever seems to think of it. Thenthey come and talk to me about picnics! What

do I care aboutpicnics?"

Jimmie loitered.

"Where I used to work b'fore, there was some reason in 'em. I never heard

tell of no picnics right on top of your mother bein'away on a visit an' your

father comin' home soon to his lunch. It's all foolishness."

Little Jimmie leaned his head flat against the wall and beganto weep. She

stared at him scornfully. "Cryin', eh? Cryin'? What are you cryin' fer?"

"N-n-nothin'," sobbed Jimmie.

There was a silence, save for Jimmie's convulsive breathing. At length

the cook said: "Stop that blubberin', now. Stop it! This kitchen ain't no

place fer it. Stop it! . . . Very well! Ifyou don't stop, I won't give you

nothin' to go to the picnic with -- there!"

For the moment he could not end his tears. "You never said,"he sputtered

-- "you never said you'd give me anything."

"An' why would I?" she cried, angrily. "Why would I -- with youin here

a-cryin' an' a-blubberin' an' a-bleatin' round? Enough todrive a woman

crazy! I don't see how you could expect me to! Theidea!"

Suddenly Jimmie announced: "I've stopped cryin'. I ain'tgoin' to cry no

more 'tall."

"Well, then," grumbled the cook -- "well, then, stop it. I'vegot enough

on my mind." It chanced that she was making forluncheon some salmon

croquettes. A tin still half full of pinkyprepared fish was beside her on

the table. Still grumbling, sheseized a loaf of bread and, wielding a knife,

she cut from thisloaf four slices, each of which was as big as a

six-shilling novel. She profligately spread them with butter, and jabbing

the point ofher knife into the salmon-tin, she brought up bits of salmon,

whichshe flung and flattened upon the bread. Then she crashed thepieces of

bread together in pairs, much as one would clash cymbals. There was no doubt

in her own mind but that she had created twosandwiches.

"There," she cried. "That'll do you all right. Lemme see. What'll I put

'em in? There -- I've got it." She thrust thesandwiches into a small pail

and jammed on the lid. Jimmie wasready for the picnic. "Oh, thank you,

Mary!" he cried, joyfully,and in a moment he was off, running swiftly.

The picnickers had started nearly half an hour earlier, owingto his

inability to quickly attack and subdue the cook, but he knewthat the

rendezvous was in the grove of tall, pillarlike hemlocksand pines that grew

on a rocky knoll at the lake shore. His heartwas very light as he sped,

swinging his pail. But a few minutespreviously his soul had been gloomed in

despair; now he was happy. He was going to the picnic, where privilege of

participation was tobe bought by the contents of the little tin pail.

When he arrived in the outskirts of the grove he heard a merryclamor, and

when he reached the top of the knoll he looked down theslope upon a scene

which almost made his little breast burst withjoy. They actually had two

camp fires! Two camp fires! At one ofthem Mrs. Earl was making something --

chocolate, no doubt -- and atthe other a young lady in white duck and a

sailor hat was droppingeggs into boiling water. Other grown-up people had

spread a whitecloth and were laying upon it things from baskets. In the

deepcool shadow of the trees the children scurried, laughing. Jimmiehastened

forward to join his friends.

Homer Phelps caught first sight of him. "Ho!" he shouted;"here comes

Jimmie Trescott! Come on, Jimmie; you be on our side!" The children had

divided themselves into two bands for some purposeof play. The others of

Homer Phelps's party loudly endorsed hisplan. "Yes, Jimmie, you be on our

side." Then arose theusual dispute. "Well, we got the weakest side."

"'Tain't any weaker'n ours."

Homer Phelps suddenly started, and looking hard, said, "Whatyou got in

the pail, Jim?"

Jimmie answered somewhat uneasily, "Got m' lunch in it."

Instantly that brat of a Minnie Phelps simply tore down thesky with her

shrieks of derision. "Got his lunch in it! Ina pail!" She ran screaming to

her mother. "Oh, mamma! Oh,mamma! Jimmie Trescott's got his picnic in a

pail!"

Now there was nothing in the nature of this fact toparticularly move the

others -- notably the boys, who were notcompetent to care if he had brought

his luncheon in a coal-bin; butsuch is the instinct of childish society that

they all immediatelymoved away from him. In a moment he had been made a

social leper. All old intimacies were flung into the lake, so to speak.

Theydared not compromise themselves. At safe distances the boysshouted,

scornfully: "Huh! Got his picnic in a pail!" Never againduring that picnic

did the little girls speak of him as JimmieTrescott. His name now was Him.

His mind was dark with pain as he stood, the hang-dog, kickingthe gravel,

and muttering as defiantly as he was able, "Well, I canhave it in a pail if

I want to." This statement of freedom was ofno importance, and he knew it,

but it was the only idea in hishead.

He had been baited at school for being detected in writing aletter to

little Cora, the angel child, and he had known how todefend himself, but

this situation was in no way similar. This wasa social affair, with grown

people on all sides. It would be sweetto catch the Margate twins, for

instance, and hammer them into astate of bleating respect for his pail; but

that was a matter forthe jungles of childhood, where grown folk seldom

penetrated. Hecould only glower.

The amiable voice of Mrs. Earl suddenly called: "Come,children!

Everything's ready!" They scampered away, glancing backfor one last gloat at

Jimmie standing there with his pail.

He did not know what to do. He knew that the grown folkexpected him at

the spread, but if he approached he would begreeted by a shameful chorus

from the children -- more especiallyfrom some of those damnable little

girls. Still, luxuries beyondall dreaming were heaped on that cloth. One

could not forget them. Perhaps if he crept up modestly, and was very gentle

and very niceto the little girls, they would allow him peace. Of course it

hadbeen dreadful to come with a pail to such a grand picnic, but theymight

forgive him.

Oh no, they would not! He knew them better. And thensuddenly he

remembered with what delightful expectations he hadraced to this grove, and

self-pity overwhelmed him, and he thoughthe wanted to die and make every one

feel sorry.

The young lady in white duck and a sailor hat looked at him,and then

spoke to her sister, Mrs. Earl. "Who's that hovering inthe distance, Emily?"

Mrs. Earl peered. "Why, it's Jimmie Trescott! Jimmie, cometo the picnic!

Why don't you come to the picnic, Jimmie?" Hebegan to sidle toward the

cloth.

But at Mrs. Earl's call there was another outburst from manyof the

children. "He's got his picnic in a pail! In apail! Got it in a pail!"

Minnie Phelps was a shrill fiend. "Oh, mamma, he's got it inthat pail!

See! Isn't it funny? Isn't it dreadful funny?"

"What ghastly prigs children are, Emily!" said the young lady. "They are

spoiling that boy's whole day, breaking his heart, thelittle cats! I think

I'll go over and talk to him."

"Maybe you had better not," answered Mrs. Earl, dubiously. "Somehow these

things arrange themselves. If you interfere, youare likely to prolong

everything."

"Well, I'll try, at least," said the young lady.

At the second outburst against him Jimmie had crouched down bya tree,

half hiding behind it, half pretending that he was nothiding behind it. He

turned his sad gaze toward the lake. The bitof water seen through the

shadows seemed perpendicular, a slate-colored wall. He heard a noise near

him, and turning, he perceivedthe young lady looking down at him. In her

hands she held plates. "May I sit near you?" she asked, coolly.

Jimmie could hardly believe his ears. After disposing herselfand the

plates upon the pine needles, she made brief explanation. "They're rather

crowded, you see, over there. I don't like to becrowded at a picnic, so I

thought I'd come here. I hope you don'tmind."

Jimmie made haste to find his tongue. "Oh, I don't mind! Ilike to have

you here." The ingenuous emphasis made itappear that the fact of his liking

to have her there was in thenature of a law-dispelling phenomenon, but she

did not smile.

"How large is that lake?" she asked.

Jimmie, falling into the snare, at once began to talk in themanner of a

proprietor of the lake. "Oh, it's almost twenty mileslong, an' in one place

it's almost four miles wide! an' it'sdeep, too -- awful deep -- an' it's got

real steamboats on it,an' -- oh -- lots of other boats, an' -- an' -- an' --

"

"Do you go out on it sometimes?"

"Oh, lots of times! My father's got a boat," he said, eyingher to note

the effect of his words.

She was correctly pleased and struck with wonder. "Oh, hashe?" she cried,

as if she never before had heard of a man owning aboat.

Jimmie continued: "Yes, an' it's a grea' big boat, too, withsails, real

sails; an' sometimes he takes me out in her, too; an'once he took me

fishin', an' we had sandwiches, plenty of 'em, an'my father he drank beer

right out of the bottle -- right out ofthe bottle!"

The young lady was properly overwhelmed by this amazingintelligence.

Jimmie saw the impression he had created, and heenthusiastically resumed his

narrative: "An' after, he let me throwthe bottles in the water, and I

throwed 'em 'way, 'way, 'way out. An' they sank, an' -- never comed up," he

concluded, dramatically.

His face was glorified; he had forgotten all about the pail;he was

absorbed in this communion with a beautiful lady who was sointerested in

what he had to say.

She indicated one of the plates, and said, indifferently:"Perhaps you

would like some of those sandwiches. I made them. Doyou like olives? And

there's a deviled egg. I made that also."

"Did you really?" said Jimmie, politely. His face gloomed fora moment

because the pail was recalled to his mind, but he timidlypossessed himself

of a sandwich.

"Hope you are not going to scorn my deviled egg," said hisgoddess. "I am

very proud of it." He did not; he scorned littlethat was on the plate.

Their gentle intimacy was ineffable to the boy. He thought hehad a

friend, a beautiful lady, who liked him more than she didanybody at the

picnic, to say the least. This was proved by thefact that she had flung

aside the luxuries of the spread cloth tosit with him, the exile. Thus early

did he fall a victim towoman's wiles.

"Where do you live?" he asked, suddenly.

"Oh, a long way from here! In New York."

His next question was put very bluntly. "Are you married?"

"Oh, no!" she answered, gravely.

Jimmie was silent for a time, during which he glanced shylyand furtively

up at her face. It was evident that he wassomewhat embarrassed. Finally he

said, "When I grow up to be aman -- "

"Oh, that is some time yet!" said the beautiful lady.

"But when I do, I -- I should like to marry you."

"Well, I will remember it," she answered; "but don't talk ofit now,

because it's such a long time, and -- I wouldn't wish you toconsider

yourself bound." She smiled at him.

He began to brag. "When I grow up to be a man, I'm goin' tohave lots an'

lots of money, an' I'm goin' to have a grea' bighouse an' a horse an' a

shotgun, an' lots an' lots of books 'boutelephants an' tigers, an' lots an'

lots of ice-cream an' pie an' -- caramels." As before, she was impressed; he

could see it. "An'I'm goin' to have lots an' lots of children -- 'bout three

hundred,I guess -- an' there won't none of 'em be girls. They'll all beboys

-- like me."

"Oh, my!" she said.

His garment of shame was gone from him. The pail was dead andwell buried.

It seemed to him that months elapsed as he dwelt inhappiness near the

beautiful lady and trumpeted his vanity.

At last there was a shout. "Come on! we're going home." Thepicnickers

trooped out of the grove. The children wished to resumetheir jeering, for

Jimmie still gripped his pail, but they wererestrained by the circumstances.

He was walking at the side of thebeautiful lady.

During this journey he abandoned many of his habits. Forinstance, he

never travelled without skipping gracefully from crackto crack between the

stones, or without pretending that he was atrain of cars, or without some

mumming device of childhood. Butnow he behaved with dignity. He made no more

noise than a littlemouse. He escorted the beautiful lady to the gate of the

Earlhome, where he awkwardly, solemnly, and wistfully shook hands ingood-by.

He watched her go up the walk; the door clanged.

On his way home he dreamed. One of these dreams wasfascinating. Supposing

the beautiful lady was his teacher inschool! Oh, my! wouldn't he be a good

boy, sitting like astatuette all day long, and knowing every lesson to

perfection,and -- everything. And then supposing that a boy should sass her.

Jimmie painted himself waylaying that boy on the homeward road, andthe fate

of the boy was a thing to make strong men cover their eyeswith their hands.

And she would like him more and more -- more andmore. And he -- he would be

a little god.

But as he was entering his father's grounds an appallingrecollection came

to him. He was returning with the bread-and-butter and the salmon untouched

in the pail! He could imagine thecook, nine feet tall, waving her fist. "An'

so that's what I tooktrouble for, is it? So's you could bring it back? So's

you couldbring it back?" He skulked toward the house like a marauding

bush-ranger. When he neared the kitchen door he made a desperate rushpast

it, aiming to gain the stables and there secrete his guilt. He was nearing

them, when a thunderous voice hailed him from therear:

"Jimmie Trescott, where you goin' with that pail?"

It was the cook. He made no reply, but plunged into theshelter of the

stables. He whirled the lid from the pail anddashed its contents beneath a

heap of blankets. Then he stoodpanting, his eyes on the door. The cook did

not pursue, but shewas bawling,

"Jimmie Trescott, what you doin' with that pail?"

He came forth, swinging it. "Nothin'," he said, in virtuousprotest.

"I know better," she said, sharply, as she relieved him of hiscurse.

In the morning Jimmie was playing near the stable, when heheard a shout

from Peter Washington, who attended Dr. Trescott'shorses:

"Jim! Oh, Jim!"

"What?"

"Come yah."

Jimmie went reluctantly to the door of the stable, and PeterWashington

asked,

"Wut's dish yere fish an' brade doin' unner dese yerblankups?"

"I don't know. I didn't have nothin' to do with it," answeredJimmie,

indignantly.

"Don' tell me!" cried Peter Washington as he flung itall away -- "don'

tell me! When I fin' fish an' brade unnerdese yer blankups, I don' go an'

think dese yer ho'ses er yer pop'sput 'em. I know. An' if I caitch enny more

dish yer fishan' brade in dish yer stable, I'll tell yer pop."

ANN.Az

Follow us !