After purging thousands of officials he said were followers of Fethullah Gulen, a cleric blamed for undermining his government, Erdogan is targeting an international network of charter schools run by Gulen’s movement. Since the start of the year, schools in Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and Gambia have closed, and education officials in Somalia, Pakistan and northern Iraq say they have come under pressure from the Turkish government to follow suit.The rift between Erdogan and Gulen represents the end of a political alliance that targeted the country’s secular traditions and paved the way for Erdogan’s populist brand of Islamism to dominate Turkish politics. In July, he warned a gathering of ambassadors against the movement’s “dangerous actions” in their countries. “I and my friends will continue to fight against these elements that threaten our national security for as long as I live,” said Erdogan, who repeated the vow after his election as president last month.The attacks reflect Erdogan’s growing sense of invincibility and threaten to “remove one of the few power bases not directly under his control” as the country drifts toward single-party rule, said Anthony Skinner, head of analysis at Maplecroft, a U.K.-based risk forecasting company in, e-mailed comments. “Erdogan’s crackdown on Gulen schools around the world is a global war against the movement.”Erdogan’s office declined to comment when contacted by telephone.Shared VisionThe hostility between Erdogan and Gulen contrasts with their former shared interests. In 2002, Erdogan’s Justice and Development party swept to power on an Islamist agenda that set it at odds with the military, the guardian of Turkey’s secular traditions.After Erdogan’s re-election in 2007, hundreds of serving or former army officers were prosecuted for alleged plots against his government, cases handled by a judiciary whose membership included Gulen’s supporters.As an imam in the 1960s, Gulen had gained a large following, which translated into a network of business interests and private schools. His movement appeared to benefit from having “loyal graduates take up top jobs in government organizations,” Osman Can, a professor of law at Marmara University in Istanbul, said in an article in Insight Turkey magazine.‘Soft Power’During Erdogan’s premiership, the Gulenist schools expanded internationally. They became a form of Turkish “soft power,” according to Bayram Balci, a visiting scholar in the Middle East program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington. “The schools sought to train elites in developing countries with values inspired by Gulen’s moderate brand of Islam.”In central Asian republics, where Gulenist schools had gained a foothold in the 1990s, educational facilities bloomed. By 2009, Kazakhstan had 30 schools and a university; Azerbaijan had 14 schools and a university. The movement also helped the Azeri government to help cultivate political support in the U.S., Buzzfeed reported in June. In Africa, school-building also accelerated, with nearly 40 primary and secondary schools being built, according to Balci.Fast FalloutThe fall-out between the two men started as Gulen’s followers objected to Erdogan’s increasing power and his shift away from the West, according to Ozgur Unluhisarcikli, Turkey country director for the German Marshall Fund of the United States, in a phone interview from Ankara. “There were questions about how to share power,” said Unluhisarcikli.Police officials with suspected ties to the Gulen movement began a corruption investigation into the government that led to a flurry of arrests, and resignations last December, before Erdogan staged a fightback. He dismissed over 7,000 officials in the police and judiciary he said were affiliated to Gulen, and threatened to close the group’s schools.Pressure has been applied by other governments, too. In Azerbaijan, a state visit by Erdogan in April was followed soon after by the dismissal of a senior official that pro-government media accused of ties with Gulen. Gulen schools were closed down in June, and later incorporated into the state education system.In a small room of a crumbling Soviet-area apartment in a Baku suburb, several Azeri supporters of Gulen were bewildered by what they see as Turkey’s crackdown. “We are not enemies of the state. We are serving Islam,” said Ahmed, who refused to give his name, citing security concerns.At least 28 schools have been closed in central Asia since January, according to local media reports.Somalia SorrowIn Somalia, the Gulen movement runs four private schools in Mogadishu, offering an international standard education that’s hard to come by in the war-torn city.Somalia’s government is coming under pressure from Turkey to close the schools, according to Mohamed Abdulkadir, the director-general of Somalia’s education ministry.“We are very much disappointed,” the deputy head of one of the schools, Mohamed Alper, said in an interview in Mogadishu, the capital. “The move is purely political.”Whether Erdogan’s attacks will be sufficient to mortally wound the Gulenist movement remains to be seen. “I don’t believe the Gulenists can be eradicated,” Maplecroft’s Skinner said. “I expect another attack against Erdogan when he is most vulnerable.”(bloomberg.com)Bakudaily.Az

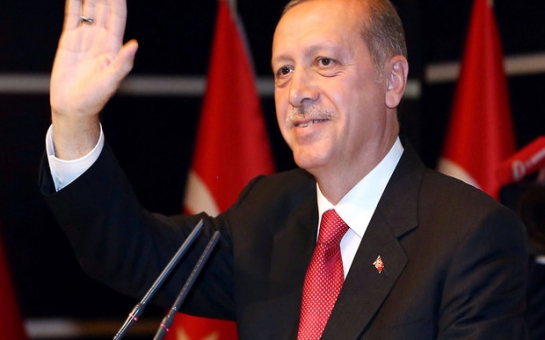

Erdogan Seeks to Vanquish Opponent Gulen in Global Fight

World

13:45 | 12.09.2014

Erdogan Seeks to Vanquish Opponent Gulen in Global Fight

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s struggle to get rid of his self-declared political enemies is going global.

Follow us !