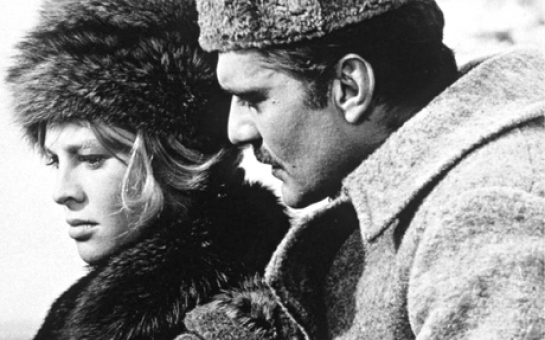

Newly declassified CIA documents suggest that in 1957 an unnamed British intelligence officer managed to photograph Pasternak's original text. Pasternak had entrusted his novel to a handful of foreign contacts the previous summer after it became increasingly clear the Soviet authorities would refuse to publish it. They included his Italian publisher, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli. Pasternak also gave the manuscript to two visiting dons from Oxford, Isaiah Berlin and George Katkov, who saw Pasternak separately at his rustic home in Peredelkino, near Moscow.It is unclear if someone from Pasternak's inner circle gave the manuscript to British intelligence to copy or if MI6 purloined it without the owner's consent. Berlin, a native Russian speaker with extensive British diplomatic contacts, is one possible source, though he opposed the novel's early publication. Katkov was in favour. After returning from Moscow Berlin also gave copies to Pasternak's sisters living in Oxford. Other possibilities include translators, as well as Feltrinelli, who brought out the first foreign edition of Doctor Zhivago in Italy that November.A CIA memo, dated 2 January 1958, reveals that MI6 delivered a copy of the original 433-page typed manuscript to American intelligence. It says: "Forwarded herewith are two rolls of film which are the negatives of the photocopy of Dr Zhivago by Pasternak. These have been given to us by xxx who request they be returned 'in due course'."The memo adds that the British – the agent's name is redacted – "are in favour of exploiting Pasternak's book and have offered to provide whatever assistance they can. They are wary, however, of mailing copies into the Soviet Union since they believe that most of them would be intercepted by the censor. They have suggested the possibility of getting copies into the hands of travelers going to the Iron Curtain area."The CIA's role in disseminating the novel inside the Soviet Union is revealed in The Zhivago Affair: The Kremlin, the CIA, and the Battle over a Forbidden Book, written by Washington Post journalist Peter Finn and academic Petra Couvée, and published next week (June 17).After receiving the manuscript from MI6, the agency secretly arranged for a Russian-language edition of Doctor Zhivago to be printed in Holland. Dutch intelligence helped publication. The edition was distributed in September 1958 at the World's Fair in Brussels, with hardback copies furtively dished out to Soviet visitors from inside the Vatican's pavilion. In 1959 the CIA printed its own paperback version of the novel at its Washington HQ. The edition was passed off as the work of a Russian émigré group in Europe.The Zhivago project had its own secret CIA codename, AEDINOSAUR. It was one of many CIA-sponsored covert publishing programmes that flourished during the cold war. The agency distributed banned books, periodicals and pamphlets and other materials to intellectuals in the Soviet Union and eastern Europe. The soft power goal was to subtly undermine the Soviet system by – as the CIA put it – "reinforcing predispositions towards cultural and intellectual freedom, and dissatisfaction with its absence".As Finn writes, Pasternak's own relationship with the Communist party and its leaders was "deeply ambivalent". He wrote poems in praise of Stalin and Lenin, but later became disillusioned with the Soviet state following the terror of the late 1930s. Pasternak survived these purges, largely because of Stalin's personal interest in his work. But many of Pasternak's neighbours in his writers' colony were arrested and shot.Finished after Stalin's death, the book was rejected by the new Soviet authorities on the grounds of its "non-acceptance of the socialist revolution". In the US, however, the CIA's clandestine Soviet Russia Division, monitored by CIA director Allen Dulles and sanctioned by President Dwight D Eisenhower's Operation Co-ordinating Board, grasped its significance. It was the perfect cold war cultural weapon. Set in the decades after the Russian revolution, its hero, the doctor-poet Yuri Zhivago, loses his enthusiasm for Bolshevism and quits the revolutionary struggle. He takes refuge with his lover, Lara, in a country house, and eventually returns to Moscow, where he dies in 1929.In a secret memo John Maury, the CIA division chief, wrote: "Pasternak's humanistic message – that every person is entitled to a private life and deserves respect as a human being, irrespective of the extent of political loyalty or contribution to the state – poses a fundamental challenge to the Soviet ethic of sacrifice of the individual to the Communist system."Maury went on: "There is no call to revolt against the regime in the novel, but the heresy that Dr Zhivago preaches – political passivity – is fundamental."Another memo describes the book as "more important than any other literature that has yet come out of the Soviet bloc". The CIA files observe that Doctor Zhivago has "great propaganda value, not only because of its intrinsic message and thought-provoking nature, but also the circumstances of its publication." The fact that Russia's "greatest living writer" was unable to publish in his own country would prompt Soviet citizens to "wonder what is wrong with their own government", the files report.After its publication in Italy the CIA and MI6 agreed the novel should appear in a "maximum number" of foreign editions. But documents suggest frustration inside MI6 at the time taken to publish an English translation. The British foreign intelligence service blamed the delay on Max Hayward, a gifted Oxford linguist recruited by Katkov to translate Dr Zhivago. "It appears work on the Collins edition is going slowly, in part because of the procrastination of Max Hayward … We also understand that difficulties have arisen in translating poems which appear in the book into fluent English and that Stephen Spender may work on this problem," the CIA wrote. (Spender did work on the poems and polished Hayward's translation.)The CIA declassified 99 secret documents from its Pasternak archive in April. They demonstrate the agency's hidden role in bringing the novel to a global audience. There had been rumours the CIA had organised a covert Russian language edition in order to win Pasternak a Nobel prize. The archive, however, shows that no copies were sent to the Nobel committee in Stockholm; instead, the CIA's aim was to spread the text among ordinary Soviet citizens. Independently, the Nobel committee gave Pasternak the 1958 Nobel prize for Literature; the writer was famously forced to decline it following a huge campaign against him, initiated by the state and embraced by many of Pasternak's fellow-writers. He died in 1960.Finn, the Washington Post's former Moscow bureau chief, notes that "in an age of terror, drones and targeted killing, the CIA's faith – and the Soviet Union's faith – in the power of literature to transform society seem almost quaint". As well as efforts by the CIA, the 1965 film of Doctor Zhivago, starring Omar Sharif as Zhivago and Julie Christie as Lara, introduced the story to "vast numbers of people", the journalist writes.Finn first asked the CIA in 2009 to release the relevant Zhivago files. The agency refused, but later relented. Names of now dead CIA officers were redacted. But Finn and Couvée were able to identify most of the main actors from public documents, interviews with their surviving relatives, and other sources. "The agency has generally been reluctant to release much material on the Cultural Cold War or its book program. But in this case, I'm guessing, they saw nothing that was damaging to the CIA," Finn told the Guardian.The authors approached MI6 to see if the agency was prepared six decades later to reveal how it had got hold of its illicit Doctor Zhivago copy. MI6 responded by saying that it had decided not to reopen its archive following the publication of its official history in 2010. Finn admitted that without further clues the mystery was unlikely to be solved. "We know of course that the publisher had a copy as did Berlin, Katkov, the Pasternak family, the translators, and a number of others. But who exactly [was the original source who gave the manuscript to British intelligence]? It's anyone's guess."(theguardian.com)Bakudaily.az

How MI6 helped CIA to bring Doctor Zhivago in from cold for Russians

World

16:00 | 11.06.2014

How MI6 helped CIA to bring Doctor Zhivago in from cold for Russians

British intelligence played a vital role in smuggling copies of Boris Pasternak's banned novel Doctor Zhivago to Soviet readers, with MI6 secretly passing the Russian manuscript to the CIA, a new book reveals.

Follow us !