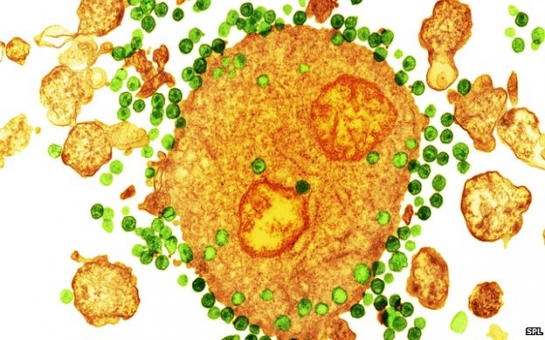

It raises the prospect of patients no longer needing to take daily medication to control their infection.The patients' white blood cells were taken out of the body, given HIV resistance and then injected back in.The small study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, suggested the technique was safe.Some patients have a rare mutation that protects them from HIV.It changes the structure of their T-cells, a part of the immune system, so that the virus cannot get inside and multiply.The first person to recover from HIV, Timothy Ray Brown, had his immune system wiped out during leukaemia treatment and then replaced with a bone marrow transplant from a patient with the mutation.Now researchers at the University of Pennsylvania are adapting patients' own immune systems to give them that same defence.Millions of T-cells were taken from the blood and grown in the laboratory until the doctors had billions of cells to play with.The team then edited the DNA inside the T-cells to give them the shielding mutation - known as CCR5-delta-32.About 10 billion cells were then infused back in, although only around 20% were successfully modified.When patients were taken off their medication for four weeks, the number of unprotected T-cells still in the body fell dramatically, whereas the modified T-cells seemed to be protected and could still be found in the blood several months later.Replacement therapy?The trial was designed to test only the safety and feasibility of the method, not whether it could replace drug treatment in the long term.Prof Bruce Levine, the director of the Clinical Cell and Vaccine Production Facility at the University of Pennsylvania, told the BBC: "This is a first - gene editing has not to date been used in a human trial [for HIV]."We've been able to use this technology in HIV and show it is safe and feasible, so it is an evolution in the treatment of HIV from daily antiretroviral therapy."He says the aim is to develop a therapy that gets people away from expensive daily medication."What if we can now take the leap to an upfront treatment that can last for years?"Such a treatment will be expensive so any benefit will depend on how long people could be freed from drugs and how long that protection would last.Prof Levine argues this could be several years, which might save money in the long term.Commenting on the findings, Prof Sharon Lewin from Monash University in Australia, told BBC News: "The idea of modifying a T-cell to make it resistant and showing it is feasible and they survive - that's exciting in itself."What most people are aiming for in HIV is a way you take treatment for a short period of time and that keeps the virus under control."She said drug treatment would not be replaced by this, especially in the early stages of the infection.But it might lead to people eventually replacing drugs with an immune upgrade, but "it's still a long way off".(BBC)ANN.Az

Immune upgrade gives 'HIV shielding'

Society

16:30 | 07.03.2014

Immune upgrade gives 'HIV shielding'

Doctors have used gene therapy to upgrade the immune system of 12 patients with HIV to help shield them from the virus's onslaught.

Follow us !