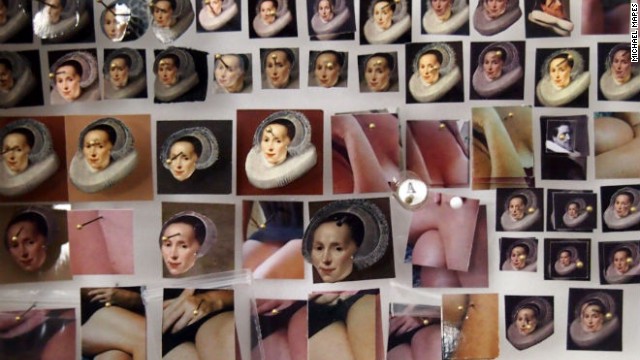

In reality, of course, to create the startlingly elaborate sculptural portraits Mapes is known for, he has to be much more organized than that. "It does take a fairly high degree of organization," assures me. "But that's not the hardest part."Take a glance through Mapes' work, and you'll understand what he means. Technically, Mapes is a portraitist, though he rarely uses paint. Instead, the artist recreates the human visage by arranging fragments of a person's life—photographs, locks of hair, handwriting samples, jewelry—into highly detailed works of art.Mapes has been making these pieces for years, generally working with subjects intimately close to him. But in his newest project, he's decided to deconstruct (then reconstruct) some of the Dutch Masters' most famous 17th century portraits, rendering classics like Bartholomeus van der Helst's painting of Geertruida den Dubbelde into startling franken-portraits.Each of Mapes' pieces are constructed from what he describes as "biographical DNA," the little pieces of physical information he pieces together to create a finished portrait. Typically, this is a fairly simple process with Mapes gathering his photos, bits of hair, and handwriting samples from his living subject's home and then organizing them into a portrait using test tubes, little baggies or pushpins. With the Dutch Masters series, he had to be a bit more resourceful.Mapes begins each portrait by downloading copyright-free images from various museums' websites. From there, he crops each image, zeroing in on certain features like an eyeball, fingertip or face before printing out dozens of each. "I'm occasionally reminded that I'm not a typical customer when the manager walks the envelope of prints out to me personally with a curious eye," he says.He considers each subject as a collection of individual parts. "I tend to produce hundreds and hundreds of samples before I start working with the actual composition," he explains. "In this way, I can work more intuitively in the composition, again, with the spirit of a painter—in a lab coat, so to speak." The process of gathering these bits of biographical DNA is an attempt to form some sort of cohesive picture about what the final portrait should look like. "I generally tape a number of photos on the wall and ponder where to go from there," he says.Of course, Mapes' final portrait is going to look a lot like the original, only with a much more of an artistically rendered shrine vibe. There are clever and nuanced departures from the 17th-century versions. For example, one thing you notice about the Dutch Masters' portraits is how utterly PG they are. Women are shrouded in black, their necks even fully covered. "These subjects were surely well known to the artists who painted them," says Mapes. "Imagine the restraint required of van der Helst in not including a bit of Geertruida's legs."At a distance, Mapes' work echoes the puritanical rigidity of the Dutch Masters, but when you get up close and really examine what his sculptural paintings are made of you'll notice photographs of bare legs and bits of cleavage filling out the skin tone of the Dutch Masters' subjects. Mapes has even incorporated locks of hair.All this is an attempt to shift our perspectives, and hopefully inspire us to re-examine how we perceive what's around us. "My hope," he says. "Is that it encourages different ways of processing and interpreting what and how we look at things—art, science or anything."(CNN)ANN.Az

Mind-blowing portraits made of test tubes and pushpins

Culture

14:00 | 01.02.2014

Mind-blowing portraits made of test tubes and pushpins

It's fun to imagine what Michael Mapes' studio must look like: You would assume that the New York-based artist's workspace has to resemble the lab of a harebrained entomologist, with test tubes, specimen bags and pushpins strewn about.

Follow us !