Follow us !

Richard Hamilton's 20th century variety show - PHOTO

Culture

21:45 | 11.02.2014

Richard Hamilton's 20th century variety show - PHOTO

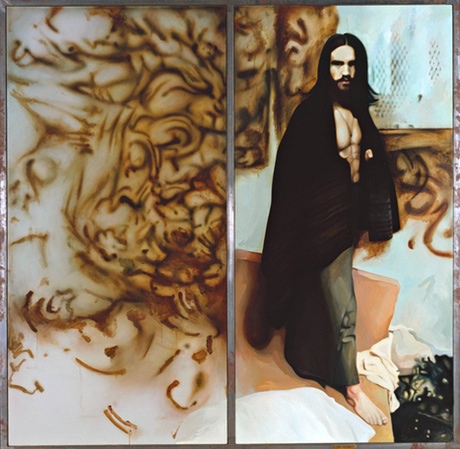

Just days before his death in 2011, Richard Hamilton completed what were to become his very last paintings. Inspired by Balzac's 1831 story The Unknown Masterpiece, they depict Poussin, Courbet and the elderly Titian standing before a computer-enhanced reclining nude. Hamilton's own presence is marked by an H-shaped easel, identical to the one he used. As a lifelong reader of James Joyce, Hamilton would have been well aware of the Irishman's playful aphorism – that absence is the greatest form of presence.The Richard Hamilton retrospective, spread across the ICA and Tate Modern in London, is filled with the twists and turns of an enquiring, analytical mind, right from his early and highly accomplished student etchings of ploughing machinery, made in 1949. Yet although the show takes us through his own development, it also marks the passage from postwar austerity and the crabbed insularity of British culture to the growth of consumerism; from rock'n'roll to the rise of TV; from the Beatles' White Album (which Hamilton designed) to the digital age. In among all this came wars cold and hot, student riots, the Troubles, Thatcherism, Blairism and the "war on terror".Hamilton pays account to it all in an exhibition, not to say a life, in which his art is shown to have had an astonishing variety and consistency of purpose. This retrospective not only tells a story, it shows us a Hamilton we probably never expected to see in full. Recreations of several exhibitions he devised or curated punctuate the show. Most of us will only know these from archive photographs, and their painstaking reconstruction is a revelation: however much they belong to their period, to actually inhabit them and walk through them brings back their inventiveness and pleasures.Old biddies on bikes and a bikini-clad girl on a scooter; deepsea divers and fantastical flying machines; astronauts in space, skiers in mid-air, photos of rockets ascending, and daft contraptions for breathing underwater – all hang over our heads and stand at our feet in Man, Machine and Motion, dating from 1955. The images are attached to 30 steel frames that fill the ICA's lower gallery. We stand among them, seeing through openings in the framework. You feel as if you're among the parachutists and speed trials, the unicyclists, cosmonauts and divers. It is an intensely visual experience.Something similar is happening in the upper gallery, as you stand in a maze of translucent plastic sheets. They hang above you, coming at you edge-first and head-on. This is Hamilton's 1957 An Exhibit, a collaborative labyrinth of a work that is an invitation to play. Its co-creators were fellow members of the Independent Group, which met regularly at the ICA in the 1950s, discussing everything from US car-styling to logical positivism, from Elvis Presley to violence in cinema. You can't escape time. But art can and does, though never in ways its makers can ever predict.Hamilton came to see exhibition-making as an artform in itself. The first room at Tate Modern plunges us into the dramatic lighting and cavernous shadows of an even earlier project: his 1951 Festival of Britain exhibition, Growth and Form. This was an homage to the Scottish biologist D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson and his 1917 book On Growth and Form – a counterpoint, development and also a critique of Charles Darwin's theories of evolution. Far from being a straightforward illustration of Thompson's ideas, Hamilton gives the biologist's observations a surrealist twist. A huge x-ray hand looms on the wall. Skulls and birds' eggs are displayed on Ladderax domestic shelving. Images of cell structures hang beside gnarled plaster versions of their basic forms, while bubbles ooze from a test tube. Very late in life, Hamilton rediscovered all his sheaves of material, photographs and notes for Growth and Form, and was persuaded that the original installation could be remade as part of this retrospective, on which he was collaborating.Hamilton was a polymath, forever exploring connections, a synthesist as much as an analytical thinker. Inspired by his regular train trips from his home in London to teach in Newcastle, the illusion of a moving landscape makes it into a series of vaguely Cézanne-like paintings mapping the constantly shifting perspective of the view through the carriage window. Meanwhile, his Independent Group conversations with architectural historian Reyner Banham led to a series that morphed American car-styling and female bodies (somehow a bit of De Kooning got in there, too). Then there was the bombshell of discovering the work of Marcel Duchamp. The two became close friends: Hamilton not only made a full-size duplicate of Duchamp's Large Glass, he also developed his own iconoclastic streak.He understood, however, that the last thing the French artist needed was any kind of academic slavery to his ideas. Hence, in part, Hamilton's lifelong devotion to painting, something anathema to hardline Duchampians. One thing he certainly absorbed from Duchamp, though, was a kind of thinking against himself: Hamilton seems to have approached painting in a spirit of disbelief. Whether he was depicting Bing Crosby or a turd at sunset on a beach, trying to paint like Francis Bacon or creating an homage to the Braun kitchen toaster, depicting his friends Derek Jarman and Dieter Roth, evoking the alienation and loneliness of the hotel lobby, or the arrest of Mick Jagger and art dealer Robert Fraser following a drugs bust, Hamilton brought to his subjects a multitude of approaches, technical innovations and stylistic twists. There is something cool to the point of cold, even frozen, about Hamilton's painting, however hot its subject matter – especially when he was depicting the dirty protests by IRA prisoners, an English soldier on an Ulster street, or an Orangeman walking through devastation.Although Hamilton has been pegged as a father figure, the originator of pop art in Britain, his interest was less wedded to pop culture than it was to other, if not all, aspects of modern life. The world of flashy cars and white goods, technology and television, and what their implications were (and continue to be) for society and for the human spirit were his larger subject.If anyone doubts his importance, this retrospective does more than confirm his significance. So many things engaged him. He never lost his didactic streak, which was always leavened by a certain wit. He could also be fierce. But best of all, Hamilton's show reminds us that artists think, and have things to say about the world that are worth attending to. The riches he achieved are endless.(theguardian.com)ANN.Az