From Brueghel’s hunters to Jeff Koons’ snowman – Aindrea Emelife picks 10 beautiful examples from 500 years of art history.

Pieter Brueghel the Elder, The Hunters in the SnowThe king of all snow scenes is by Flemish painter Pieter Brueghel the Elder. There are fundamental difficulties that come with depicting snow – it needs to hint at depth, texture and coldness to evoke that overall ‘brrr’ feeling. This wonderful Renaissance panel isn’t festive or idyllic however – there is not a snowman or filigree snowflake to be seen. Brueghel was commissioned by a merchant from Antwerp to create the painting, just one from a series of six, to reflect the labours of the months. In the far corner we see some hunters returning with lacklustre pickings from their day of hunting (just one rabbit does not a Christmas dinner make). It’s an exhausting scene – people scavenge and toil, but skaters also skid with joy, a contrast that is both compelling and powerful. There is a sense of the stresses and expectations of winter, as they trudge leaving man-hole sized footprints in their wake. It is interesting that art history’s most recognisable snow scene is one of melancholy – but there is truth as well. With winter comes the biting freezing cold. And no one likes the cold.

Hokusai, Tea House at Koishikawa – The Morning After a SnowfallNatural imagery is at the very core of Japanese art and this landscape by Hokusai is testament to this. Paintings that depict a single environment’s transition into a season were a distinctive Japanese convention. Hokusai evokes winter by blanketing this tea house in a cartoon-like sheath of snow. Japanese painters sought to emphasise nature in their art works as a way to demonstrate their Buddhist beliefs. The images highlight an awareness of the inevitably of change but also their joy in the natural cycle of the seasons.

Though seemingly innocent, the characters – diminutive in comparison to the expanse of the landscape – have lascivious intentions. During the Edo period (1603-1868) in which Hokusai worked, a ‘tea house’ was often a place where couples retreated for privacy, or where men could procure geishas. The steaming beverage was purely incidental.

Edouard Manet, Effect of Snow at Petit-MontrougeWhen it snows in a city it doesn’t stay picture-perfect, crisp and white for long; the French painter Édouard Manet shows urban snow as it really is here. Between the large peaks of white and diagonals of murky brown we can make out the Paris district of Petit-Montrouge, overshadowed by the dirty snow and bleak beige sky. The buildings seem to balance precariously on a huge expanse of brown. Manet was never one to sugar-coat things – but this image eschews snow’s association with purity and tranquility, focusing instead on the problematic effects of extreme weather. From 1870 to 1871 Manet served in the National Guard during the Franco-Prussian conflict. The foreboding dusk and sludgy melted snow could suggest a battle looming ahead – but there is no heroism or triumph here. Battle or no battle, the weather is one of life’s great equalisers.

Turner – Snowstorm, Steam boat off a Harbour’s MouthIt is famously reported that to create this image, JMW Turner was tied to the mast of a ship for four hours, during an actual storm. While the story is almost definitely untrue, it’s a wonderful contribution to the myth of this great painter.

You can just make out the forms and shapes in Turner’s haphazard brushstrokes; a paddle-steamer negotiating the turbulent waters, snow and sea merging as the elements collide. Turner is the uncontested champion of depicting the natural world exercising its control. In this image, we are drawn to the steam boat, puny and humble in the heart of this great elemental vortex. We could think of it as a symbol of mankind’s efforts, in vain, to triumph over nature.

Franz Marc, Haystacks in the SnowFranz Marc was one of the key members of the German Expressionist movement. He usually painted animals, so this painting is quite the anomaly. His oeuvre is characterised by the use of bright, primary colours and his near-Cubist simplifying of forms that is reminiscent of Kandinsky and Matisse. There is a stark simplicity and a profound sense of emotion, even in this seemingly straightforward composition of orange, red and green haystacks. Marc gave emotional meaning or purpose to the colours he used, and while red generally denoted violence, these snowy mounds seem innocent – they look like a bowl of pears dusted with icing sugar. The image is unassuming, but nonetheless, these snowy peaks show the seasons changing and suggest our reluctance to change. ‘Make hay while the sun shines’ the old proverb goes, but in truth, time all too often escapes us and we find our haystacks covered in snow. And no one likes a soggy haystack.

John Nash, Melting Snow at WormingfordJohn Nash is the less famous brother of the artist Paul Nash. While his older brother sought out new, exciting challenges, Nash Junior was comfortable with his East Anglian landscapes, which he mastered.

Here, the artist gives us a field striped with snow. It’s as quintessentially English a landscape as you’ll find and there is more green than white. But the touches of snow have an element of hope – spring is coming, nature renews itself once more. It reminds us that all things pass but also that some things never change.

Lee Miler, Paris in the snowElizabeth Lee Miller is often discussed in relation to the Surrealist photographer Man Ray, with whom she was romantically involved. Their relationship is important – not least as Lee rediscovered the solarisation technique and enabled some of Man Ray’s greatest images. But Miller is important in her own right as a photographer, not just a muse, and as the creator of some outstanding snapshots of France, such as this image.

It’s in black and white and so the snow, rather than gleam and sparkle, is dulled – but then that’s what snow is like when it falls in the city. We trudge through it, cars trundle through it – snow is rarely white in the modern age. The stark contrast between the lonely silhouette of a man and the white expanse is ominously reminiscent of the art of the Romantic era, when no good ever came from a shadowy suited figure in the distance. The statues on the building look towards the centre as if to mirror this anxiety. Or perhaps they, like the shadowy man, are focused on the Eiffel Tower. Indeed, the great symbol of Paris, obstructed by the snowy mist, gives us hope and reminds us too to look ahead; a message all the more potent in recent times.

Jeff Koons, SnowmanIf you think about it, there is no better example than the snowman of how easy it is to create order from artificial signs. They are, after all, just massive snowballs accessorised to denote human characteristics. Jeff Koons’ kitsch rendering looks like a blow-up doll. His snowman carries a large blue orb in the artist’s trademark shiny metal. Koons has made snow textureless, without imperfectiona, but that goes against all we know to be true. It’s a textbook winter image – but the inscrutable snowman is somehow rather chilling.

Annette Lemieux, Potential SnowmanAnnette Lemieux is part of a global wave of artists that emerged in the 1980s. With a typically adversarial approach, she presents a deconstructed snowman. Lemieux doesn’t muck about. Her work addresses weighty issues – the nature of time, the truth of ideas – but not without humour. The clinically white Potential Snowman consists of three spheres, a carrot nose, and a selection of coal – all drained of colour. They seem not to have progressed beyond their plaster beginnings. You might say it looks unfinished – indeed it could be a snowman, but it’s not yet. You’ll have to paint the nose orange, the coal black, and arrange all the pieces to create the familiar form. The work was created as a response to the events of 9/11, which tempers the wintery cheer somewhat.

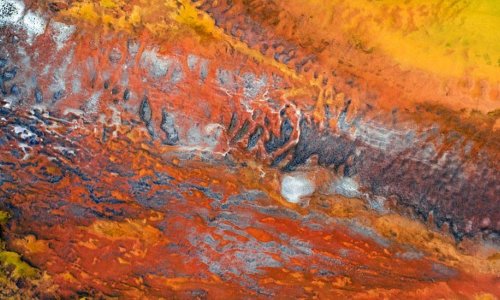

Yayoi Kusama, Snowball in Sunset (Snow Ball in Sansunset)This one looks more like a fireball than a snowball but when has Yayoi Kusama, Japan’s dotty conceptual artist, ever played by the rules? Snowball in Sunset is one of her early works from a series of drawings produced in Japan from 1953 to 1957. At this time she was just starting to explore her legendary dot aesthetic, as demonstrated by the obsessive repetition of unwieldy fields of dots in intense colours. This high-octane image of what seems to be a snowball with a glowing red and blue aura defies nature. The snow looks like it’s on fire. But in some ways it doesn’t look like a snowball at all. Rather, we see the Earth, with all its greenery crystalised and caked with the cold white powder – or maybe we see the sun. If only we all saw the world like Yayoi Kusama.

(BBC)

www.ann.az

Follow us !