by Sara Oghuz Nazirova

Since time immemorial every mahalla or district in the historic inner city of Baku had its own hamam – from single-domed bath-houses to more grandiose 12-domed affairs, there was a hamam to suit every whim. But on no account did local people go to wash in another mahalla. Every family, young and old, went to the hamam in the mahalla where they lived. That’s what people did – they lived and grew old, bathing in their local hamam. There was regular weekly bathing, known as haftahamam, and special visits such as vajibat and janabat. Before important events in their lives, men performed the ritual ablutions in the hamam which their grandfathers and great-grandfathers before them had frequented.

Special bathing

Weekly visits to the hamam – haftahamam – were obligatory for all members of the family. The vajibat ablution was performed by a family in which someone had died away from home. After the funeral, all the members of the family of the deceased had to bathe. After bathing, each person would throw a bucket of water first over their right shoulder, then over their left, and a third bucket over their head, and say a prayer of mourning: Messi-meyit qusulu eleyirem, vajibat-qurbati illallah (I am performing the ritual ablutions after touching a dead body, as required by God). Girls and women completed the janabat ritual wash after their monthly periods or after intimacy with their husband and the men after intimacy with their wives. They would give the reason for their ablutions and pray. In one of Jalil Mammadguluzadeh’s stories, a mullah performed the temporary marriage known as sigheh every day, then went to the hamam to perform the janabat ablutions required by propriety.

If the oldest woman in a family went to the hamam of another mahalla, this would cause an immediate commotion – everyone realized that she had come to find a girl to be her son’s bride. The appearance of a woman in the hamam to choose a bride was practically as good as marriage. Each woman thought it their duty to pour water on the guest’s head at least once. Since that time, it has become a tradition to cement a friendship with water in the hamam.

Bride

The bathing of the bride was a whole ritual. The bride’s attendants would paint her hands and feet with henna, while her girlfriends sang:

Yes, I’ll paint your hands with henna,

Yes, I'll place a sacrifice at your feet.

Slim, made beautiful with moles

A feast for the eyes!

Take the henna, oh bride,

Apply the henna, oh bride!

May your beloved be healthy, oh bride!

May your face be white, oh bride!

One girl would sing the verses and the others would join in the chorus:

Oh bride, made beautiful with moles,

Oh bride, your mouth is sweet as honey.

The bride’s girlfriends also bathed together with the bride. Then the meshshateh would take over – the woman whose job it was to dress and do the bride’s hair and make-up before taking her to the groom’s house. Another name for the meshshateh was the bash bezeyen or beautifier-in-chief. The meshshateh would finish off her work back at the bride’s home, using unguents and ointments diluted with goat’s fat.

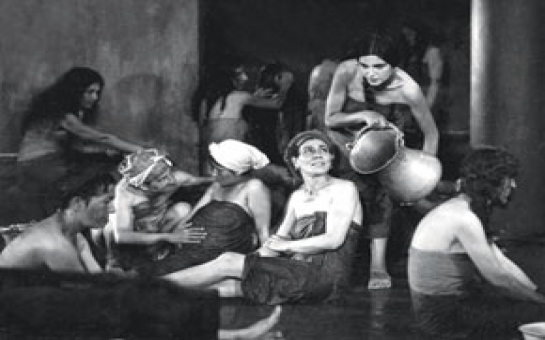

Groom

The groom’s ablutions were an equally grand affair. May this be the fate of all bachelors, as the saying goes. Men, who like to look after their bodies, would wrap themselves in a red cloth – a fite – from the chest to the knees and go into the steam room. From the steam room they would plunge into the pool of cold water, from the pool they would go back to the steam room, and there surrender to the hands of the kisechi, the masseur who would rub and knead every fibre in their bodies. After this, they had to make it to the tea ceremony, complete with dates, baklava and roasted chickpeas that had been simmered first in milk, and then they could fall sweetly asleep. Often, the exhausted hamam attendant could not help nodding off next to the customers. It was hard work to be a kisechi in the hamam. Always in a wet room saturated with steam, kisechi were prone to rheumatism and respiratory problems. However, their skilled hands could expel any disease from the body. Their hands were healing in every sense of the word and could make an old man young. The groom paid for both his own and his bride’s ablutions. Presents were also given to the attendants.

Of particular importance was the red colour of the fite. It is not a shroud so should not be white. The hamam means looking after the body, health and youth, so the cloth should be a joyous, invigorating colour. To make the event even more joyful, musicians were also invited to the hamam. It was impossible for the bride or groom to bathe in the hamam without singers being present. No matter how close the bride or groom’s house to the hamam, they would return home in an open carriage, cruise the streets to take the air, please their friends and infuriate their enemies.

Accoutrements

Even the accoutrements for the hamam were assembled in a special order. There was everything – snuff, a saucer for the henna which would be applied to beards and moustaches, a fite, a change of clothes, a kisa – a glove for scrubbing the skin, pumice and a comb for beards. The only thing that was never taken was scissors or a razor, because cutting nails in the hamam was considered indecent. It was a barber’s job to cut hair, as he had the right tools. Nothing foul-smelling was taken to the hamam either. In contrast, no one stinted on perfumes and fragrances – especially musk perfume oils, which make the skin soft, even the hard, coarse skin of old men.

In the Azerbaijan State Museum of Art, you can see all the items that our ancestors took with them to the hamam. The exhibition shows caskets with lockable lids known as satil. Women would put their jewellery in the casket, lock it and hand it to the hamam attendant. These copper containers were real works of art – they would be decorated with lines from the Eastern poets, botanical designs, even with scenes from the classic love story Leyli and Majnun.

When getting ready for the hamam, a woman would put on her best dress and take all her jewellery, because the hamam was a meeting place for women who spent their lives at home. Here they could chat, swap advice and gossip. One woman might want to annoy her friends with her jewellery, another might want to hear the news – in short, the main women's issues were dealt with in the hamam, underground rivers of feminine wiles mixed with hamam water.

Boys went to the men’s hamam with their fathers, and girls to the women’s hamam with their mothers. If a mother took her three- or four-year-old son with her to the hamam, a sharp-tongued gossip might loudly ask the age of the child. And if the boy tried to add years to his age and say he was more than four, she would act surprised and ask why the boy didn’t go to the men’s hamam with his father. Women would tease the child so much that he would refuse to go to the hamam with his mother any more.

Modern writers drool as they write about how the boys in those days would peep through the openings in the hamam’s dome. However, this is not true. No one, not even the most mischievous rogue, would have thought of spying on women bathing. First of all, it would have meant acknowledging their own bad manners. Second, it might have led to a blood feud, not to mention punishment from the relatives of these women or the local gochu (bandit chief).

Cleanliness next to godliness

The hamam was not just a place for health, cleanliness and well-being, but for socializing too. Even some of our fairy tales begin in the hamam.

In his Journey to Erzurum Russian poet Alexander Pushkin wrote enthusiastically about the Eastern hamam. The hamam is evidence of the level of culture. In Azerbaijan, there were hamams which were heated by a single candle. Unfortunately, in trying to discover their secret, our contemporaries destroyed these hamams. In the heat of the hamam, the human voice resonated, and bathers would burst into song like a nightingale.

Cleanliness starts with a clean body. Just as a person might seek to maintain the purity of their soul, they should preserve the purity of the body, the abode of the soul. Moreover, hamams resemble mosques in terms of architecture – they have domes and niches and lack only the minarets.

May your body not know disease, may you always be healthy! Restore all the hamams in the city, including the hamams in the walled Old City. Don’t turn them into cafes or bars, don’t discredit the hamam!

About the author: Sara Oghuz Nazirova, an Honoured Arts Worker of Azerbaijan, is an art critic and writer of novels, short stories, plays and film scripts. Her Selected Works were published in English in 2009.

Baku still has working hamams, including the 18th century Agha Mikayil Hamam in the Old City. The hamam is open to women on Mondays and Fridays, and men the rest of the week. At the time of writing, entry and bathing cost 10 AZN while massage or kise (a scrub with pumice) costs an additional 10 AZN. Tea is available for 2 AZN and tea with jam for 4 AZN. The hamam is at 3/16 Kichik Qala Street, just inside the city walls. To reach the hamam, enter the Old City through the pedestrian gate up from the Four Seasons Hotel, turn left and walk up the road 150 metres or so. The hamam will be on your right.

(Visions.az)

ANN.Az