Art and mathematics. For many, this would appear to be synonymous with chalk and cheese. One is the domain of emotional expression, passion and aesthetics. The other, a world of steely logic, precision and truth. And yet scratch the surface of these stereotypes and one discovers that the two worlds have much more in common than one might expect.

Any creative artist will tell you that the emotional resonance of a piece emerges out of the construction of the work and is rarely an ingredient fed in at the beginning of a composition. The composer Philip Glass admits that he never deliberately programs any emotional content in his work. He believes it’s generated spontaneously as a result of all the processes that he employs. "I find that the music almost always has some emotional quality in it; it seems independent of my intentions.” The structure and internal logic of a piece is what drives its composition.

Perhaps more surprising is the role that emotions and passion play in the mathematics that we humans create. Mathematics is far from being just a list of all the true statements we can discover about number. Mathematicians are storytellers. Our characters are numbers and geometries. Our narratives are the proofs we create about these characters. Not every story that it’s possible to tell is worth telling.

I have spent many years as a mathematician working alongside artists and what has struck me is how similar our practices are. I have so often found artists drawn to structures that are the same ones I am interested in from a mathematical perspective. We may have different languages to navigate these structures but we both seem excited by the same patterns and frameworks. Often, we are both responding to structures that are already embedded in the natural world. As humans we have developed multiple languages to help us navigate our environment.

Music is probably the artistic discipline that traditionally has resonated most closely with the world of mathematics. As the German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz once declared: "Music is the pleasure the human mind experiences from counting without being aware that it is counting.” But this connection goes much deeper than that. The very notes that we respond to as harmonic have a mathematical underpinning, as Pythagoras famously discovered. And mathematical structures also inform the architecture of composition.

Take the 20th-Century composer Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time. In this piece, Messiaen creates an extraordinary sense of tension by employing one of the most important sequences of numbers on the mathematical books: the primes. In the opening movement, Messiaen uses the indivisible numbers 17 and 29 to create a sense of never-ending time.

If you look at the piano part, you'll find a 17-note rhythmic sequence repeated over and over – but the chord sequence that is played on top of this rhythm consists of 29 chords. So as the 17-note rhythm starts for the second time, the chords are just coming up to about two-thirds of the way through its sequence. The effect of the choices of prime numbers 17 and 29 are that the rhythmic and chords sequences won’t repeat themselves until 17 times 29 notes through the piece, by which time the movement has finished.

The intriguing thing for me is that the musician and the mathematician’s attraction to primes to keep things out of synch can already be found in the natural world. There is a species of cicada that lives in the forests in North America that has a very curious life cycle: the cicadas hide underground doing nothing for 17 years and then, in the 17th year, the insects emerge into the forest for a six-week party. At the end of the six weeks they all die and we have to wait another 17 years before the next generation emerges. This prime number life cycle is believed to be connected with its ability to keep the species out of synch with a predator that also appears periodically in the forest.

Between the lines

While the abstract quality of music might make it a natural partner with mathematics, the other arts also provide fascinating examples of mathematical ideas bubbling away underneath the artist’s output. The visual arts have an obvious connection to mathematics given that every time you paint a line on a canvas or carve a surface from a sculpture, geometry is emerging. Architecture has a very necessary connection with mathematics, which is what guarantees the building will make it from the drawing board to the city landscape. But the shapes and forms that now populate the skyline are as informed by the aesthetic of mathematics as by its power to ensure the building doesn’t fall down.

For me, one of the most exciting revelations has been that even the art of the written word has mathematics hidden inside it. Poets, playwrights and novelists have all played around with exciting forms and patterns and frameworks that have mathematical shapes to them.

In my radio series The Secret Mathematicians, I have explored the artistic practices of a whole range of composers, writers, architects and artists. Through their work I look at the range of mathematical ideas they have been drawn to, sometimes consciously but often quite unconsciously.

Philip Glass is fascinated by the power of number to create rhythms that draw the listener into his meditative world, rhythms that nature beats to. The Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges strove to find an explanation for the shape our finite universe by writing The Library of Babel; and Zaha Hadid’s parametricism movement is helping to seed our urban environment with forms that are both mathematical and natural at heart.

In my programme on visual art, I investigate how Renaissance artists helped mathematicians of the period rediscover shapes first found by the ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes – their descriptions had been lost over time, but they were uncovered through developments in drawing.

I find a hyper-dimensional solid in one of Salvador Dalí’s most famous works, Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus), and discover how Jackson Pollock was unconsciously tapping into geometric structures called fractals – shapes that mathematicians only discovered in the 20th Century. The US artist was a secret mathematician by virtue of his lack of balance and penchant for alcohol, using what mathematicians call a ‘chaotic pendulum’ when staggering around to create his drip paintings.

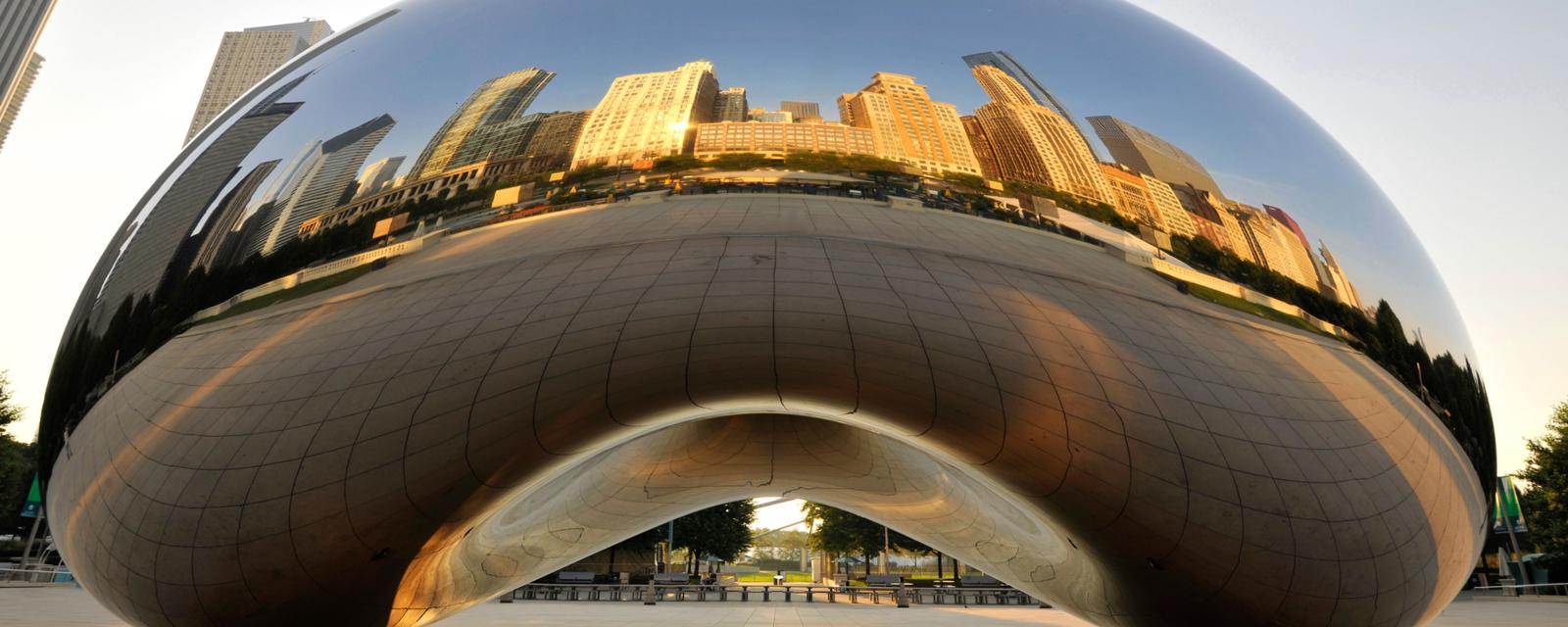

Anish Kapoor originally wanted to be an engineer but gave up after finding the maths too challenging. Yet his works reveal an extraordinary sensitivity to mathematical structures, shapes that are universal and not bound by cultural reference. His 2009 tower of spherical balls, called The Tall Tree and the Eye, created reflections that are fractal in nature, while his hyperbolic mirrors distort our environment to create a strange new perspective on the world. Kapoor’s curved mirrors provide a lens to see the universe as it really is: curved, bent, where light is warped on its way through space and our intuition is turned inside out.

(BBC)

www.ann.az

Follow us !