BY ELIZABETH MINKEL

When the book was handed to me, I didn’t know where to begin. Its two hundred oversized, glossy pages were filled with beautiful but impossibly foreign illustrations, men and women from a time and place I couldn’t really pinpoint. It cast a powerful spell: everyone who came to my house noticed the bright orange cover, picked up the book, and disappeared for twenty minutes or so. “Can I borrow this?” they’d ask me without looking up. When it came time for my own disappearing act, it was the first few sentences that pulled me in:

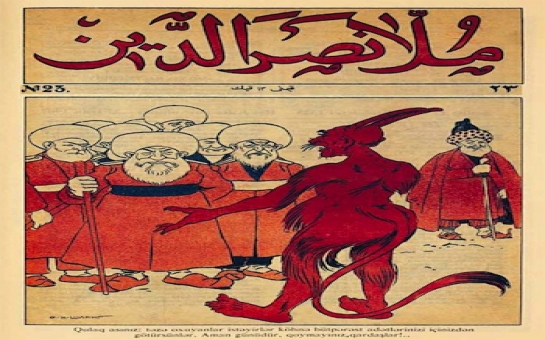

We first came across Molla Nasreddin several years ago on a cold winter day in a second-hand bookstore near Maiden Tower in Baku. It was bibliophilia at first sight. Its size and weight, not to mention print quality and bright colour, stood out suspiciously amongst the more meek and dusty variations of Soviet brown in old man Elman’s place. We stared at Molla Nasreddin and it, like an improbable beauty, winked back at us.

The book is “Molla Nasreddin: The Magazine that Would’ve, Could’ve, Should’ve,” and its subject is the aforementioned Molla Nasreddin, a “satirical Azeri periodical” published in the first three decades of the last century in Azerbaijan and “read across the Muslim world from Morocco to Iran.” Nasreddin is a traditional character dating back to the Middle Ages in Central Asia, and he served as the magazine’s unifying figure. The book, which gathers some of the best images and guides the reader through their cultural nuances, is a project of the international artists’ collective Slavs and Tatars, who describe themselves as “a faction of polemics and intimacies devoted to an area east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China known as Eurasia. The collective’s work spans several media, disciplines, and a broad spectrum of cultural registers (high and low) focusing on an oft-forgotten sphere of influence between Slavs, Caucasians, and Central Asians.”

Molla Nasreddin was revolutionary in many ways. In an era and a region where free speech wasn’t particularly encouraged, its authors boldly satirized politics, religion, colonialism, Westernization, and modernization, education (or lack thereof), and the oppression of women (Azerbaijan was surprisingly progressive on women’s issues at the time, granting women the right to vote in 1919—a year before the United States). And with the majority of the population at the time illiterate, the magazine was a careful and clever blend of illustrations and text. And the text itself might be the most interesting of all: it was written in Azeri Turkish, rather than Russian, the language of their colonizers. The book’s editors had the unenviable task of sorting out the text: the Azeri alphabet, written with Arabic characters for nearly a millennium, was Latinized by Lenin in 1928, Cyrillicized by Stalin a decade later, and returned to Latin following the fall of the Soviet Union.

Slavs and Tatars will be touring the world with the book and accompanying art installations for the rest of the year: Vienna now, Art Basel, in Switzerland, in June, Munich in August, Brazil in September, Minsk in October, and Stuttgart in 2012.

(The New Yorker)

Bakudaily.Az