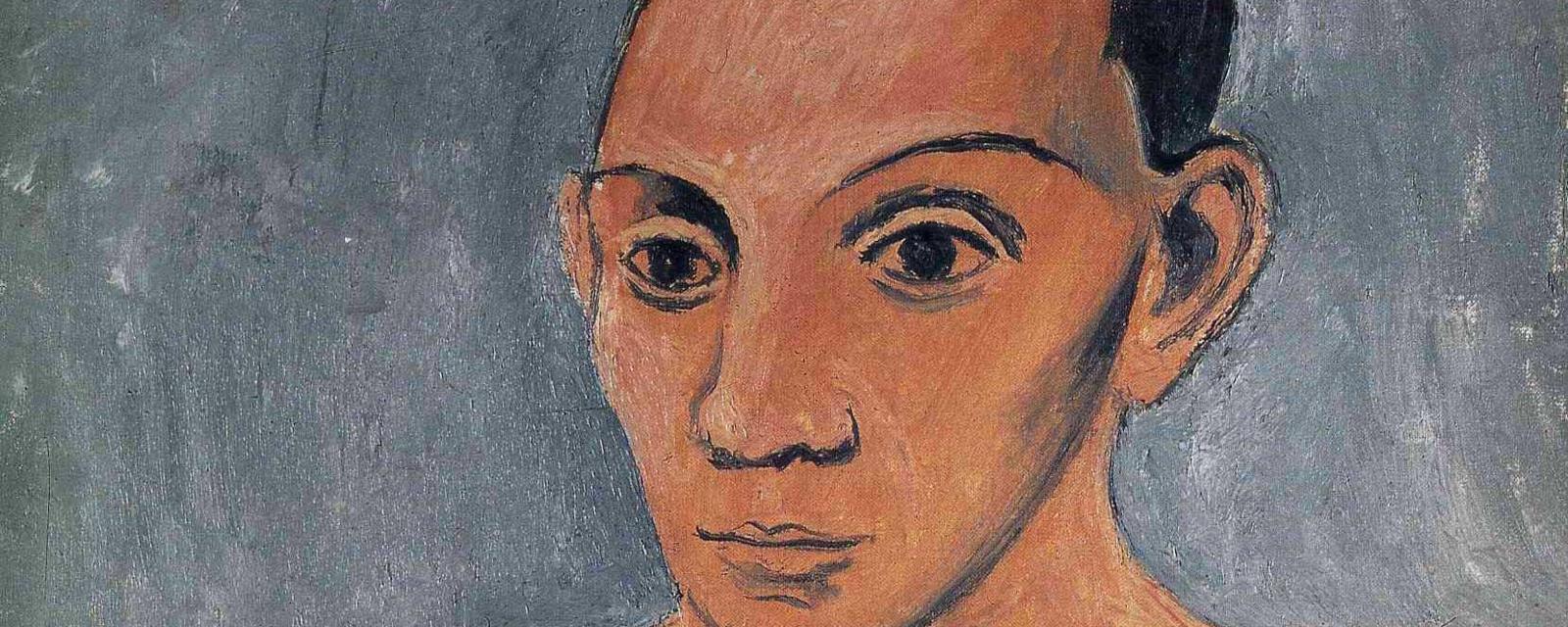

A short trip to an ancient village was the catalyst for a profound shift in Picasso’s work – but it is often overlooked. Alastair Sooke finds out more.

One day in June 1906, Pablo Picasso arrived in the ancient Catalan village of Gosol, high in the Pyrenees. A friend had tipped him off about this "magnificent” mountain refuge, which was notorious for its smugglers. Intrigued, he had persuaded his mistress, the chic, auburn-haired former artist’s model Fernande Olivier, who had a penchant for French perfume, to go with him on the arduous journey to Gosol from Barcelona, where they had spent a happy couple of weeks catching up with Picasso’s old friends after travelling to the city by train from Paris.

The alarming final approach to Gosol had to be undertaken on mules, which picked their way up precarious mountain tracks beside terrifying precipices. Upon arriving, Picasso and Olivier took a room on the first floor of the village’s only inn, the Hostal cal Tampanada. The plan was to while away the summer painting and enjoying the pleasures of a simple life.

Art historians ascribe special importance to Picasso’s time in Gosol, because there, in self-imposed exile from the backbiting Parisian art world, he changed his art dramatically and profoundly.

By 1906, Picasso had already enjoyed a taste of success in Paris, the epicentre of the avant-garde at that time. His 1901 debut Paris exhibition at the gallery of the dealer Ambroise Vollard had received positive reviews. Moreover, in the American collectors Leo and Gertrude Stein, he had found two important champions. But his melancholic and sentimental Blue and Rose period paintings, as brilliant as they were, were still indebted to 19th-Century art movements such as Symbolism.

When he arrived in Gosol, though, Picasso’s art was moving in a new, startling, and more original direction. It was beginning to feel tougher and simpler, stranger yet more timeless. Picasso sensed this change, and revelled in the rapture of inspiration. During his stay in Gosol, which lasted around 10 weeks, he was remarkably prolific: according to his biographer, John Richardson, he produced seven large paintings, a dozen medium-sized ones, and countless drawings, watercolours, gouaches, and carvings.

Skulls and smugglers

What was the catalyst for this transformation and excitement? There are several possibilities. Many of Picasso’s Gosol works feature Olivier, for instance, suggesting that the 24-year-old artist’s feelings for his lover were then especially intense.

There was also his new friendship with Gosol’s wily nonagenarian innkeeper, Josep Fondevila, a former smuggler with a shaved head and brilliant white teeth whom Picasso greatly admired. Certainly, Fontdevila’s severe, ascetic appearance began to infiltrate Picasso’s art, and it remained a touchstone until his death (witness the late skull-like self-portrait that the artist drew in 1972).

But Picasso also encountered something else in Gosol that altered his approach to painting: a 12th-Century polychrome wooden Madonna, with a strong, expressive white face with big, painted eyes, which he saw in the village church.

Today, this 77cm-high (30in) sculpture, which is considered a fine example of Catalan Romanesque art, is part of the collection of Barcelona’s Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (MNAC). It currently plays a starring role in MNAC’s Romanesque Picasso, a show featuring around 40 artworks by the Spanish Modernist. This exhibition suggests "affinities” between Picasso’s work and the holdings of medieval Romanesque art, mostly from churches in the Pyrenees built during the 11th to 13th centuries, for which MNAC is internationally renowned. One glance at the Gosol Madonna, for instance, reveals that it was a source for Picasso’s painting Woman with Loaves (1906).

The thing is, while art historians are aware that Picasso was looking with interest at Romanesque art in the years leading up to his invention of Cubism, they tend to overlook its impact upon his development, preferring instead to concentrate on better-known influences such as African tribal art, archaic Iberian sculpture, and Cezanne.

"While Picasso’s ‘primitivism’ has always been known,” says MNAC’s director Pepe Serra, "what is clear upon seeing the show is that Romanesque art was also one of the most important sources for him. The exhibition demonstrates that there is a very strong connection between Picasso and Romanesque art.”

‘Creative lifeblood’

It is likely that Picasso first started looking seriously at Romanesque art four years prior to his trip to Gosol, when a major exhibition of Romanesque and Gothic art opened in Barcelona, coinciding with a resurgence in Catalan nationalism. A little over three decades later, in 1934, by which time Picasso was an international celebrity living permanently in France, the artist returned to Barcelona to visit the new National Museum (then known as the Art Museum of Catalonia), shortly before its official inauguration.

A newspaper covered the event, which proved to be Picasso’s last visit to his homeland – after the rise of Franco, he never returned to Spain. "Passing from one room to another,” the reporter wrote, "Picasso, before those incomparable fragments of early Catalan art, admired [their] power, intensity and skill … and he stated without hesitation that our Romanesque Museum will be something unique in the world, an indispensable resource for anyone who wishes to know the origins of Western art, an invaluable lesson for the moderns.”

Throughout his life, as MNAC’s exhibition reveals, Picasso amassed many books, postcards and photographs documenting Romanesque art, attesting to his enduring interest in the subject. In this, he was not alone. Joan Miró, for instance, another great modern Spanish artist, was also compelled by Romanesque art, which he studied as a boy growing up in Barcelona. When asked how much it meant to him, Miró used to tap the veins in his forearm. It was in his creative lifeblood.

What, then, was the "invaluable lesson” that Romanesque art taught both Picasso and Miró? According to MNAC’s director, Picasso was drawn to the "simplicity” of Catalan Romanesque art: "It’s a naive, very ‘primitive’ art,” Serra explains. "For example, perspective is not used, and it is extremely schematic in the composition of the faces, which appealed to Picasso. It is also full of symbols – eyes, fires, fish – that represent other things.”

"And there is another big link with Picasso in terms of the subjects: the violence, the dismembered bodies, the skulls, crucifixions, the presence of death. So, there are thematic links as well as stylistic ones.”

Elizabeth Cowling, emeritus professor of art history at the University of Edinburgh and curator of Picasso Portraits, an ongoing exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London, agrees: the aspects of Romanesque art that most appealed to Picasso, she says, were "the stylisation, the intensity and forcefulness, the fact that it wasn’t driven by a naturalist aesthetic”.

Like Serra, she believes that Picasso’s stay in Gosol in 1906 was "very important”, because it was "the break that gave him the opportunity to absorb sources he’d recently discovered more fully and develop ideas and themes outside the competitive environment of a major city. And being such a backwater – so unmodernised – it must have reinforced his well-established penchant for the primitive.”

Indeed, Picasso’s wider interest in primitivism helps to explain his fascination with Romanesque art. "Primitivism is a huge subject,” says Cowling. "But, very broadly, primitivists had a sense that the ‘primitive’ was more authentic and purer than sophisticated Western art of the Renaissance and post-Renaissance periods. There’s a strong element of anti-naturalism at its core, and also anti-academicism – so anything that was considered ‘canonical’ at the time was liable to be rejected by primitivists.”

In other words, the Romanesque offered Picasso a revelatory model as he battled to dismantle and reassemble the great tradition of Western art. As Cowling puts it: "Picasso was never passive when it came to sources of inspiration – he got excited by new discoveries, but I think he was attracted to a new source because it chimed with something that already interested him, that meant something for his current work.”

(BBС)

www.ann.az

Follow us !