There may have been earlier public squares, yet the ancient Greeks with their agora, or central meeting place at the heart of their cities, made this form of urban space not just famous, but compelling too. Every public square since, not just in the Western world, but around the globe, has had something of the agora about it. This is where tradespeople and philosophers, poets and politicians rubbed shoulders and where, too, the public complained and demonstrated and, at times, were met, dispersed and even slaughtered by forces of the regimes they tried to take to task.

So, while the agora was a special and often hugely enjoyable place, it should be no surprise that it also gave us the word agoraphobia, a fear of public places. For centuries, and certainly today, public squares have been places of protest, of violence and even revolution. The roll call of disturbing public squares is long: Tahrir, Taksim, Tiananmen, Trafalgar. And this is just the entry for ‘T’.

Place de la Concorde, despite its name, was anything but peaceful during the 1968 student riots in Paris. Palace Square, St Petersburg, will be associated forever with the October Revolution that brought Lenin and the Bolsheviks to power in 1917. Moscow’s Red Square is a vast space we associate with Lenin’s tomb and bombastic annual displays of Soviet, and now Russian, military hardware. The Plaza de la Revolución, Havana, is where, in his prime, Fidel Castro would address crowds a million strong in the years following the revolution that overthrew the US-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959.

Recently, scenes of violence concentrated in public squares have been screened in our homes from Tripoli, Istanbul, Cairo and Kiev, and vast parades of political-military power brought to us from Beijing and Pyongyang. Some of the most violent protests in Britain in living memory took place in Trafalgar Square in 1990 over the ill-advised poll tax proposed by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government. No matter how politically mature and socially content a major city might seem, its public squares are always at risk, so history tells us of erupting into violence. The public square is not just a meeting place, but an urban safety valve. It is a place, too, where people come to celebrate, to let rip, to unzip the certainties of everyday life.

Focal point

Because they are the central focus of most major cities, they have also long been places where much architectural intelligence, money and culture have been expended. The Forum in ancient Rome, long a ruin, was made magnificent by the Emperor Augustus, while other Roman squares from the 1st to the 20th centuries are an essential part of the life of the Eternal City. Who could fail to be moved by the Pantheon, the domed temple to all the gods that fills one side of the Piazza della Rotunda? Who can fail to share in la dolce vita at the nearby Piazza Navona in the early evening as the young, and young at heart, parade between the voluptuous fountains of this Baroque urban stage set? And, whatever your religious beliefs, or lack of them, St Peter’s Square is a thrilling place to be, with crowds held happily in the embrace of the magnificent 17th Century colonnade created by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Although these great city squares are naturally the focus of attention, many of the world’s most impressive and enjoyable city centres boast whole sequences and networks of squares: London with its restful, if all too-often locked, garden squares; Turin with its glorious colonnaded Baroque piazzas; Venice with its campi, ancient fields long paved over. Rarely less than magical, these are often a relief – a physical and psychological release – after the city’s narrow streets and maze-like alleys.

The grandest of these is Venice’s Piazza San Marco, a square Napoleon Bonaparte is said to have described as "the drawing room of Europe”. Although often too popular for anyone’s comfort, this remains an enchanting space. Enclosed on three sides by regimented ranks of colonnaded classical buildings, the fourth opens up to the fulsome, Byzantine glory of Saint Mark’s Basilica and its celebrated campanile, rebuilt in 1912 after the original collapsed a decade earlier, killing no one except the caretaker’s unfortunate cat.

When city squares get too big, they lose any sense of embracing their public. Squares like Tiananmen and perhaps even Mexico City’s Plaza de la Constitución – the great meeting place of the former Aztec city, Tenochtitlan – can induce agoraphobia in almost anyone. The former was extended in the late 1950s by the Chinese leader Mao Zedong, who wanted nothing less than the world’s biggest public square. Other contenders for this dubious honour like Merdeka Square, Jakarta, or Xinghai Square in Dalian, the seaport in China’s Liaoning Province, are more urban parks than city squares.

Heart of the city

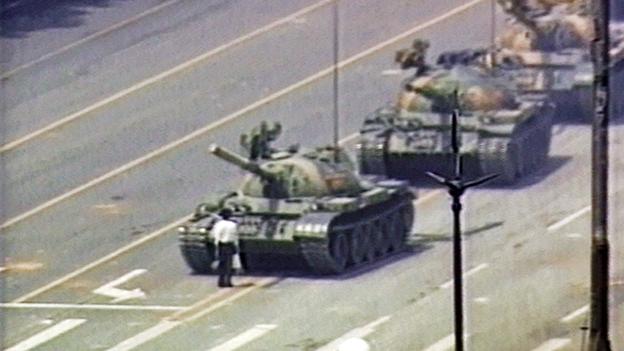

On sultry summer or bleak winter days, Tiananmen Square is a decidedly challenging terrain. The might of the People’s Republic was challenged here in 1989 by a popular pro-democracy movement. On 5 June of that year, police and military opened fire, killing hundreds and possibly thousands of protestors. Tiananmen Square is named after Tiananmen Gate, or the Gate of Heavenly Peace. The most haunting image from that horrendous day was that of a lone man, dressed in white shirt and carrying a shopping bag in both hands, facing down and taunting a column of battle tanks rumbling along Chang’an Avenueat the north end of the square. No one admits to knowing who this brave man was or what happened to him: Tiananmen Square swallowed him up.

In recent years, not only have many of the world’s major cities invested in their historic squares, but the very idea of the piazza, plaza or square has become almost fashionable. Run-down squares in the United States are coming alive again, like Houston and Pittsburgh’s Market Squares and Detroit’s Campus Martius, its name alone taking us back to the proud public spaces of imperial Rome. Perhaps the key to the popularity of these revived squares is that they are truly places for people to meet. This might sound all too obvious, and yet some of the world’s grandest squares are little more than giant junctions and speedways for furiously fast traffic. The Place de la Concorde in Paris, for example, is always something of a disappointment because it is so very difficult to walk, let alone meet here.

There has long been a tendency, though, for imperious political regimes, including those of Napoleon and Mao Zedong, to sweep away the messy, uncertain human life that gave the Greek agora its special place in the Athens of Pericles, and to replace its quotidian life with the pomp of processions, politics and soldiery. And yet despite the ways cities have grown and sprawled, their centres are especially important. At their very heart is the agora, the democratic meeting place: the public square.

(BBC)

ANN.Az

Follow us !