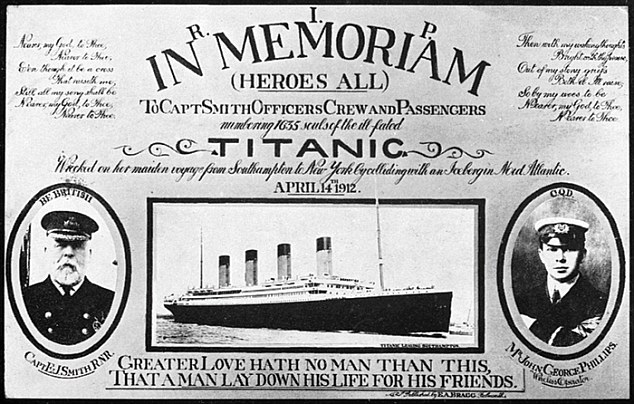

On the night that the Titanic sank, one woman, the Countess of Rothes, put the welfare of others before her own, working tirelessly to row them to safety. Angela Young tells her great-grandmother’s incredible story

My great- grandmother Noël, Countess of Rothes, was born on Christmas Day 1878. She was christened Lucy Noël Martha but was always known as Noël after the day she was born. She lived until she was 76 – a long life for those times – but she might easily have died at sea at the age of 33 when, in 1912, she sailed from Southampton on board RMS Titanic.

Noël boarded Titanic with her parents, Thomas and Clementina Dyer-Edwardes, her husband’s cousin Gladys Cherry and her maid Roberta Maioni. Her parents disembarked at Cherbourg on the evening of 10 April. If they hadn’t, her father would surely have died just a few days later.

When Titanic hit the iceberg just after midnight on 15 April, Noël was ordered into the lifeboats, as were all the women and children, while the men were held back.

But the sailor in charge of her lifeboat, Able Seaman Thomas Jones, didn’t think her a woman at all: ‘When I saw the way she was carrying herself and heard the quiet, determined way she spoke to the others,’ he said later, ‘I knew she was more of a man than any we had on board.’

Noël had become châtelaine of Leslie House in Fife when, in 1900, she married my great-grandfather, Norman Evelyn, the 19th Earl of Rothes. She oversaw a large household of staff, so she knew about encouraging, managing and gently persuading people to do as she asked. And my great-grandfather owned a yacht, so she also knew how to row and to take a tiller – unusual skills for a woman in those days. But Able Seaman Jones knew nothing of this, he only saw that the other two men who had boarded his lifeboat in the confusion weren’t seamen (one was a steward, the other a cook) so, when he saw the calming effect Noël had on the terrified female passengers, he put her in charge of them. And when he realised that she knew about boats he put her at the tiller.

Noël boarded lifeboat number eight at one in the morning and for the entirety of that long, cold and frightening night, while she helmed the boat, or rowed, or taught others to row, or comforted the distraught women, she thought about her two young sons safely at home, and prayed she would see them again.

It wasn’t until much later that she learned that, at exactly one in the morning, far away in Scotland, her eldest son, ten-year-old Malcolm, had woken up, shivering and terrified, calling out, ‘Mama’s in danger! Mama’s very cold!’ He knew in his heart that something terrible had happened, despite being thousands of miles from her.

But on the night Titanic hit the iceberg, even Noël, who understood the sea and boats well, didn’t imagine anything too serious had happened.

She left her cabin on C-deck and went up three decks to the boat deck just to see what an iceberg looked like. She and all the other passengers had absolute faith in Titanic’s unsinkability.

Afterwards Noël wrote to her parents, ‘The order came to be dressed and have life belts on in ten minutes. I just had time to pour out some brandy, give Maioni some and Gladys and myself, and hurriedly dress. Then no one seemed to know where the life belts were kept, and a strange man found ours for us – we tied on his for him – and all shook hands and told each other it would not be long before we met again, as we all thought there were plenty of boats, little knowing there were only 16.’

The women were relatively lucky: 75 per cent of them were rescued safely, while only 19 per cent of the men survived. And as we all now know, many more men would have been saved if there had been more lifeboats, or if the existing lifeboats had left Titanic at full capacity.

On lifeboat number eight a terrible argument broke out when the passengers saw Titanic’s lights go out and the ship begin sinking. As the ship tipped up vertically, all the heavy machinery, the engines and the boilers came loose and the noise as they fell was deafening. ‘It was as if,’ wrote Lawrence Beesley in The Loss of SS Titanic, ‘all the heavy things one could think of were being thrown downstairs from the top floor of a house and smashing themselves and everything on their way to bits.’

Those in lifeboat number eight argued bitterly about whether to go back to pick up more of the people who had been thrown into the icy water.

However, many were afraid that their boat would be overturned when stricken people struggled to board it, or that Titanic’s suction would drag the lifeboat under.

Noël, Able Seaman Jones and one or two other passengers tried to persuade the rest that they must return to pick up as many from the water as they could because their own boat was only half full. But when the majority wouldn’t be persuaded, Able Seaman Jones said, in despair, ‘Ladies, if any of us are saved, remember I wanted to go back. I would rather drown with them than leave them.’ But those who didn’t want to return outnumbered those who did, so lifeboat number eight didn’t turn back.

(dailymail.co.uk)

ANN.Az

www.ann.az

Follow us !