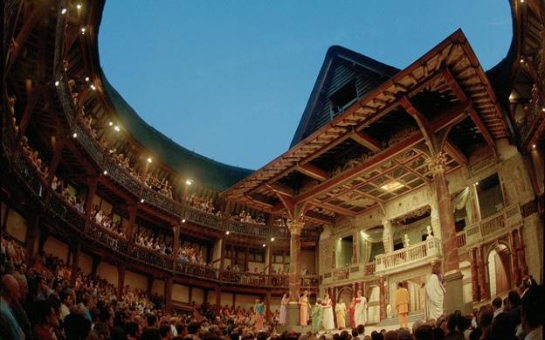

Shakespeare was fascinated by the word ‘world’. He used it at least 650 times in his published writings, from poems written in his twenties to troubling late plays such as The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest. The lovelorn aristocrat Orsino talks in Twelfth Night of how his love is “more noble than the world”, just as the narrator of the Sonnets describes “the wide world dreaming on things to come”. In Antony and Cleopatra – where the word occurs more than any other – “world” is used to describe everything from getting drunk Egyptian-style (one of Cleopatra's servants sniggers that "the least wind in the world" will blow the inebriated Romans over) to a measure of how much the heroine adores the hero. In the mouth of Beatrice from Much Ado about Nothing, it is a euphemism for marriage: “Thus goes everyone to the world but I,” she sighs, little knowing that she too will end up hitched before the play is done. And the word even sneaks its way into one of Shakespeare’s most famous lines, spoken by the Eeyorish Jaques in As You Like It, who informs his fellow characters (and us in the watching audience) that “all the world’s a stage” – a chill reminder that most of us are mere extras in someone else’s drama. It is often said that Shakespeare is the world’s writer, and the 450th anniversary of his birth this month is being celebrated with the unveiling of a statue in Weimar, at academic institutions in Washington DC and Paris, inside theatres in Beijing, and with 154 YouTube videos shot in New York City (not to forget the playwright’s home town of Stratford-upon-Avon, which is offering a souped-up version of its annual birthday parade). That’s fitting: in the four centuries since he died, Shakespeare has been translated into more languages than any other writer, from Arabic to Zulu, and must be the most performed and adapted playwright on the planet. When it comes to global fame, not even Agatha Christie and Danielle Steele come close .Wandering thoughtsBut what of Shakespeare’s own view of the world? How did the planet and its inhabitants inform the worlds he put on stage? How did he see what Prospero in The Tempest – no doubt with a sly glance around Shakespeare’s theatre – calls “the great globe itself”?In real life William Shakespeare does not seem to have done much travel: he was born in Stratford-upon-Avon, died there and spent most of his life, so far as we know, in London. Plot his life on a map and it would track what is now a motorway corridor between London and Birmingham. He may possibly have worked as a schoolteacher in northern England. Even that’s not certain.Yet, in and through the drama he put on stage, Shakespeare’s mind roamed free: into the temples of lost civilisations and onto dusty ancient battlefields; up to the ramparts of Danish castles and Scottish hill forts; across swaths of the eastern Mediterranean and down through the Levant into Turkey and Egypt. He had a fascination with Italy, especially the glittering cosmopolitan city of Venice (setting for two plays, The Merchant and Othello), and a minor obsession with islands, both real (Cyprus, Sicily) and imagined (The Tempest’s nameless “isle”). His casts number Venetians, Viennese, Moroccans, ancient Romans, ancient British, ancient Trojans, ancient Greeks, not to mention entire phalanxes of medieval Welsh, Irish and English soldiers and a troupe of French lords who dress up as Russian Muscovites.To be sure, many of these settings are hardly literal: on the bare stage of the Globe or Curtain theatres in London, all it took was for a change of scene and perhaps a prop or two for Lebanon to dissolve into Turkey, or the regimented world of Athens to transform into the mysterious forest in A Midsummer Night's Dream.Most of As You Like It is set in a wood called Arden, which seems to be simultaneously in Warwickshire and the great forest of the Ardennes, and is also a natural habitat for lions, one of which attacks the hero. And Shakespeare wasn’t above the odd geographical blunder: he seems to imagine Milan as a port, while in The Winter’s Tale, landlocked Bohemia (present-day central Poland) inexplicably acquires a sea – an error mocked by his friend and rival Ben Jonson.Expanding horizonsBut perhaps even those so-called mistakes, if they are mistakes, suggest that Shakespeare's worldview was all but boundless. Born in 1564, he was of a generation of British people whose horizons expanded enormously during their lifetimes, from the haphazard explorations of Elizabethan privateers during the 1560s and ‘70s to organised expeditions to India, Indonesia and beyond by the East India Company, founded in 1600 just as Shakespeare was working on Hamlet. Jamestown in Virginia was settled by Europeans in 1607, while English merchants and travellers had long been busy on the trade routes through Europe and up into the Baltic. Hamlet itself appears to have been remarkably mobile: the play was adapted in Germany during Shakespeare’s lifetime, and may even have found its way on board an East India Company ship in 1607, when it was performed off the coast of Sierra Leone by – improbably enough – an amateur cast of sailors. Nor was Shakespeare under any illusions about to the costs of colonisation. In 1603 a group of Native Americans were captured near Chesapeake Bay and shipped back to London to be shown off to gawping crowds, an episode grimly hinted at in The Tempest. That play also makes pointed space for the character of Caliban – an islander forcibly dispossessed by the European magician Prospero. And conflicts closer to hand repeatedly make themselves felt in his work. In London Shakespeare lodged with a family of French Huguenot refugees, economic migrants after the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre of 1572, and it’s fascinating that the only play to survive in what appears to be his handwriting is the little-known Sir Thomas More. This was a collaboration with a group of playwrights where Shakespeare was brought in specifically, it seems, to write a section on the sufferings of illegal immigrants. “Grant them removed,” says More, addressing a mob who wants to do just that:“and grant that this your noise Hath chid down all the majesty of England.Imagine that you see the wretched strangers,Their babies at their backs, with their poor luggage,Plodding to th’ ports and coasts for transportation …”It has been observed that exile is Shakespeare’s great abiding theme.Sometimes, as here, Shakespeare seems to be using the “wide world” as a filter for uncomfortable home truths. His bleak comedy Measure for Measure is set in the fleshpots and brothels of Vienna, but the city is London in all but name: the zealous moral clean-up initiated by a politician at its opening echoes a similar project by James I, and the play itself was performed in front of the king in December 1604. That very fact meant Shakespeare had cause to bury the parallel – playwrights who were less politic had their plays cut or, if they were more unlucky, their ears. But it isn’t just that. He seems to have actively attempted to distance his work from the realities of his own life, not simply holding the “mirror up to nature” (as Hamlet describes the actor’s art) but attempting to darken and distort it.Shakespeare’s global popularity is sometimes used as an index of colonialism – and in places like India and South Africa, where his works were exported during the 19th Century as part of the imperial education system, those origins are hard to deny. But it’s also true that, like a plant adapting to new terrain, they outgrew that purpose almost immediately, pushing down roots into fresh soil. At the same moment Shakespeare was being employed as an obedient servant of the Raj, he was also fuelling a late-19th-Century Renaissance in Indian playwriting and poetry, and helping lay the foundations for homegrown Indian film.That has to be, I think, because Shakespeare himself had such an expansive and open sense of place. It doesn’t matter whether you act his plays or read his poems in Philadelphia or the Philippines, Chennai or Chorley, Stratford-upon-Avon or Stratford, Ontario; they will find a way of touching a nerve, of touching home. In all their multiplicity, multitude and variety, Shakespeare’s works are themselves alive to what the globe can contain. If he is now the world’s favourite writer, it is because he had a sense of how large the world could be.(BBC)BakuDaily.Az

Why Shakespeare is the world’s favourite writer

Culture

20:04 | 23.04.2014

Why Shakespeare is the world’s favourite writer

Although he never left England, Shakespeare’s plays are set around the globe and he is the planet’s most famous playwright. Andrew Dickson finds out why.

Follow us !