A 1916 silent movie featuring Sherlock Holmes - long presumed lost - is due to have its premiere in Paris. It stars a man who changed the way we see Conan Doyle's famous sleuth forever.

He was the first great Sherlock Holmes. But few will have heard of US actor William Gillette.

He is thought to be a distant relation of the family behind Gillette razors, wrote plays about the American civil war, patented a noise to imitate the sound of a galloping horse and built an enormous castle in North Carolina. But it is his Holmes that fascinates people today.

And until three months ago, it seemed that no-one would ever see it.

Gillette adapted Sherlock Holmes for the stage in 1899 and played Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's detective more than 1,000 times.

He made only one film, the 1916 silent movie version of Sherlock Holmes. For decades the movie was presumed lost, one of the great missing links of Sherlockiana. Then in October 2014 it was discovered at the Cinematheque Francaise, a film archive in Paris.

"At last we get to see for ourselves the actor who kept the first generation of Sherlockians spellbound," says the man supervising the film's restoration, Professor Russell Merritt. "As far as Holmes is concerned, there's not an actor dead or alive who hasn't consciously or intuitively played off Gillette."

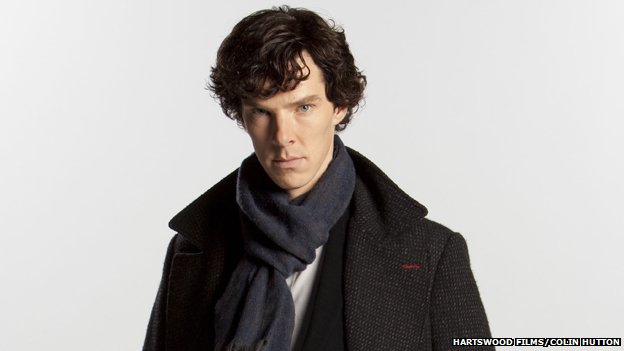

Not only was Gillette the Benedict Cumberbatch of his day. He was the actor who decided - perhaps more than any other - how Holmes looks and talks, and whose relationship with Conan Doyle may have breathed new life into the Sherlock Holmes franchise.

Here are five ways Gillette created the Holmes we know today.

Curved pipe

Two props evoke Sherlock Holmes above all others.

The first is the deerstalker. Conan Doyle's stories never mentioned his distinctive headgear - it was given to Holmes by the illustrator Sidney Paget when the stories were published in the Strand Magazine in 1891.

The other crucial object is his pipe. It's not an ornament but a part of Holmes's deductive ritual. "It is quite a three pipe problem, and I beg that you won't speak to me for fifty minutes," he says to Watson in the Red-Headed League.

The books describe a "black clay pipe thrusting out like the bill of some strange bird". Paget gave Holmes a straight pipe.

But William Gillette's 1899 play and 1916 movie, in which he played Holmes, made a crucial change. The shaft of the pipe was no longer straight but curved.

"The story goes that he's able to deliver his lines while still smoking. A more traditional pipe and his hand would have been in front of his mouth," says Alex Werner, curator of the Museum of London's ongoing exhibition, "Sherlock Holmes: The Man Who Never Lived and Will Never Die."

The curved pipe stuck in the popular imagination and became "iconic", Werner says.

There have been occasional amendments though. In the 1988 film Without a Clue, Michael Caine puffs on a more ostentatiously curvy pipe. And in the recent BBC TV series, Benedict Cumberbatch has a nicotine patch instead.

'Elementary, my dear fellow'

The most Holmesian phrase - "Elementary my dear Watson" - is never uttered in the books. Gillette is perhaps the man who did most to bring it in, although he never used the exact phrase.

In the play he wrote the line: "Elementary my dear fellow." Others subsequently swapped "fellow" with "Watson".

PG Wodehouse is often credited with this swap in his spoof novel Psmith. But the Oxford English Dictionary queries this.

It seems that the term was already being used in newspapers before Wodehouse's 1915 novel. So some uncertainty remains as to who coined it.

Conan Doyle included the term "elementary" in Holmes's deductive vernacular. He also included "my dear Watson". But never in the same sentence.

It seems that Gillette almost put the two together. And others later finished the job. The line, "Elementary my dear Watson" probably became famous when the talkies came in - it was used in The Return of Sherlock Holmes in 1929, which starred Clive Brook.

(BBC)

ANN.Az

Follow us !