Over her 30-year career, the Iraqi-born, London-based designer developed a style more recognisable, and more imitated, than any of her contemporaries, transforming what began as world of dreamy abstract paintings into a global brand for daring art galleries and experimental opera houses that now dot the globe from Baku to Guangzhou.

In her best buildings, the laws of physics appear momentarily suspended. Walls melt into floors, ceilings ripple and bulge, facades dissolve into perforated skins and flowing veils, transporting the visitor to another dimension. They can feel like sublime landscapes, sculpted by an irresistible geological force. Swimming beneath the whale-like roof of her London aquatics centre , or walking under the coffered concrete underbelly of the Phaeno science centre in Wolfsburg , can be a thrilling experience, leaving you in thrall to the feats of structural gymnastics on show.

On other occasions, the ambitious schemes dreamed up on planet Zaha struggle when they crash down to earth and are forced to meet reality. Her first built work, a small fire station the Vitra furniture campus in Switzerland, famously sent its users round the bend, its wayward walls and aggressive angles driving the firemen to distraction.

Nor have the sloping surfaces of the Maxxi museum in Rome given its curators the easiest time of hanging work. Her recent building for St Anthony's college in Oxford, , meanwhile, smashes into its historic neighbour with the same thuggish inelegance as her Serpentine Sackler Centre does in London. For all her wonders, it is fair to say there were an equal number of blunders.

At the time of her death, Hadid was one of the most sought-after architects in the world, perhaps even the best known living architect. She had a portfolio brimming with ongoing mega-projects, from the World Cup stadium in Qatar to a clutch of towers and cultural projects in China, Russia, Mexico and Miami (where she died suddenly of a heart attack after contracting bronchitis), as well as a line of luxury homeware in Harrods . Creator of an entire "parametric" universe beyond buildings , she designed a handbag for Fendi, vases for Lalique, and a perfume bottle for Donna Karan, as well as the obligatory luxury yacht and even a raunchy range of swimwear .

But her feted starchitect status wasn't easily won.

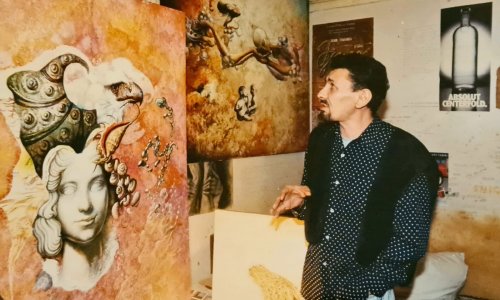

After graduating from London's Architectural Association in 1977, having first studied mathematics in Beirut, she remained a "paper architect" for years. She produced intricate paintings and exquisite paper relief sculptures of fractured landscapes and skewed perspectives, drawing on the abstract energy of the Russian suprematists' images of colliding planes and shards floating in space, but she did not get a chance to build until the 1990s.

In 1995, the year after her fateful fire station project, she suffered a loss that would haunt the rest of her career, when her winning design for the Cardiff Bay opera house was cancelled, a decision she put down to prejudice against her being a woman and a foreigner. She would go on to build her seminal opera house 15 years later, in the Chinese city of Guangzhou instead, a project that has been showered with accolades – even if the cladding panels have been known to fall off and are now bodged together with mastic.

Determined to push the limits of structural engineering and material science (as well as her clients' pockets) with every project, her work was inevitably never far from controversy. Every major international award was met with an equal outcry, from the human rights claims surrounding her Heydar Aliyev centre in Azerbaijan , to the cost overruns of the London Olympic pool, to the lethal cocktail of escalating budget, sensitive context and local architectural opposition that finally put paid to her scheme for the Tokyo Olympic stadium last year, which was perhaps her most bitter loss of all.

She was always characteristically blunt in the face of such criticism, accusing Japanese architects of jealousy over her win and, when questioned about conditions of labourers in Qatar , simply responding: "It's not my duty as an architect to look at it." When asked why the roof of her Olympic pool had to use 10 times the amount of steel as the velodrome to cover the same approximate span, she simply rolled her eyes. To have admired her genius, you had to forgive her shortcomings.

Twice winner of the Stirling prize, for the Maxxi and the Evelyn Grace Academy school in Brixton, Hadid finally received the RIBA gold medal last year. As her former tutor Peter Cook put it, when she was awarded the prize: "Let's face it, we might have awarded the medal to a worthy, comfortable character. We didn't, we awarded it to Zaha: larger than life, bold as brass and certainly on the case."

The world of architecture would certainly have been more dull without her.

www.ann.az

Follow us !