America and Azerbaijan: Five Reflections on the Contract of the Century

RICHARD KAUZLARICH

Azerbaijan—the oil-rich dynasty that borders Iran and Russia, abuses human rights, and peddles influence throughout the West—has shifted from being an essential U.S. energy partner to a competitor. The former U.S. ambassador speaks out on the energy diplomacy he witnessed—and why we need a new approach to Baku today.

On September 20, 1994, representatives of 11 international energy companies, the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan (SOCAR), six foreign governments, and the Government of Azerbaijan signed a production sharing agreement to develop oil fields in the Azeri sector of the Caspian Sea. Known as the Contract of the Century, it was the foundation for the development of the Azeri energy sector in the late 20th and early 21st century. Smaller projects with fewer participants would follow, but none had the commercial or geopolitical significance for the United States or Azerbaijan.

Twenty-five years later, the agreement has guaranteed oil and gas production worth nearly $200 billion, while paving the way for the construction of multiple international oil and gas pipelines. No one present at the Gulestan Palace signing ceremony could have imagined the scope of these developments. As U.S. Ambassador in Azerbaijan from 1994 to 1997, I witnessed this event, the creation of the Azerbaijan International Operating Company (AIOC) in February 1995, and the intense struggles over the route for "early oil” that followed. With the benefit of over two decades of hindsight as a diplomat and intelligence analyst, I offer the following five reflections.

Reflection 1: It Was the Right Thing to Do

Azerbaijanis and foreigners alike have criticized Western governments for facilitating the development of energy resources. These resources, the critics argue, only enabled the Aliyev dynasty to expand its oppression of domestic critics and continue the military confrontation with Armenia over the Azeri territory of Nagorno-Karabakh. I disagree. U.S. government support for the signing and implementation of the Contract of the Century was necessary to provide Azerbaijan with any hope for political and economic development. In 1994, it was not clear that there would be enough oil to justify the development of offshore Azerbaijan oil and gas, or that there would be a pipeline grid that could move this energy to world markets. U.S. support amid these uncertainties was a risk worth taking to give Azerbaijan a chance to ensure its independence, prosperity, and sovereignty and to enhance our geopolitical role in the region.

Reflection 2: It Was a Success that Cannot Be Repeated

U.S. negotiators took justifiable pride in the role the U.S. government played in providing the geopolitical support necessary for Azerbaijan and the international energy companies to develop its offshore resources, and ultimately the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline. This was a case study in aligning corporate, host government, and U.S. geopolitical interests.

It was not easy. On the corporate side, BP had its specific objectives regarding the pipeline route—first preferring a southern route to Iran, then a path through Russia. The major U.S. energy companies, however, had a direct interest in the transportation of this oil to the West, which provided leverage for the U.S. negotiating team to achieve its geopolitical objective of a pipeline route that avoided both Iran and Russia. The interests of U.S. corporations—eager to avoid the experience in Kazakhstan, where companies were beholden to the Russian Transneft pipeline system to move their oil to Western markets—uniquely aligned with U.S. foreign policy priorities. The leadership of Azeri President Heydar Aliyev was also essential. He saw the advantage of a U.S. geopolitical role in the development and transportation of Azerbaijan’s oil, to balance against Iranian and Russian efforts to undermine Azerbaijan’s independence.

Sometimes the lessons of success are harder to learn than those of failures. Today’s energy mix relies heavily on gas developed by non-U.S. companies. Trying to repeat a diplomatic formula from the 1990s can only distract from developing a new U.S. strategy tailored to deal with the changed energy situation of the 21st century. Gas and oil infrastructure needs are quite different, and as the Nord Stream 2 experience illustrates, negotiations are much more complicated when commercial and geopolitical objectives are not aligned.

Reflection 3: Russia and Iran Tried to Undermine Azerbaijan’s Energy Independence—and They Haven’t Stopped

Russia and Iran always considered a Western-led consortium for the production and transportation of Azerbaijan energy westward to be against their interests. Both tried to insert themselves into the production consortium of international energy companies (the Azerbaijan International Operating Company, or AIOC) and SOCAR.

Azerbaijan offered the Russian private energy company LukOil, headed by Azerbaijani-born billionaire Vagit Alekperov, a 10 percent share in AIOC. At the time, LukOil lacked the capital to pay for its share. Heydar Aliyev saw the value of a Russian energy partner inside the AIOC "tent”—and Washington agreed. Western oil companies reportedly helped "carry” LukOil to allow it to be an AIOC partner.

Iran tried a similar approach with the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC). When President Heydar Aliyev informed me of the possibility that Iran would receive a share, I told him—on instructions from Washington—that if Azerbaijan went ahead with this, it would trigger sanctions under the Iran and Libya Sanctions Act (ILSA), and U.S. companies would withdraw from the consortium. President Aliyev informed the Iranians and offered them a consolation prize: a 10 percent share in the Shah Deniz gas development, which involved no American companies.

U.S. political engagement was critical to supporting the AIOC consortium and blocking continuous Iranian and Russian efforts to use the uncertain status of the Caspian Sea to upset this Western-led energy effort. Today, Russia and Iran are using environmental loopholes in the recently signed Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea to block a Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline from Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan.

Reflection 4: On Corruption and Human Rights, We Came Up Short

Since the signing, this project and the Shah Deniz gas field have generated billions in revenue for the state of Azerbaijan. Sadly, corruption and prestige projects have wasted much of this treasure, which should have been used to addressing income disparity and pressing social needs in Azerbaijan. Today, the corruption and grotesque inequality in Azerbaijan are all too apparent—as in the infamous case of the Azerbaijani oil scion who owned a watch worth $1.35 million. The Contract of the Century, and the prospect of a White House visit for President Aliyev, gave us leverage that we did not effectively use to press for political and economic reforms necessary to anchor Azerbaijan firmly in the West.

Addressing democracy is a long game; observing international standards for human rights and freedom of expression cannot wait. Why not? Because unlike in 1994, today we have instruments in place (thanks to the Global Magnitsky Act) to directly sanction individuals engaged in corruption and human rights violations. There is no excuse, and no threat—internal or external—that should justify continued suppression of human rights in Azerbaijan. Nor is there an excuse for us in the United States to turn a blind eye to such abuses.

Reflection 5: In Nagorno-Karabakh, the "Freedom Support Act” Backfired

We did not use the leverage that the energy deal provided to advance the diplomatic process toward resolving the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. That tragic dispute between Azerbaijan and Armenia has created thousands of casualties and hundreds of thousands of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) while draining both neighbors of the resources necessary to develop and reform. It has also provided both Iran and Russia with leverage to increase their political and security presence in the region.

Further aggravating this issue was Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act, known as FSA 907. This addition to the first U.S. assistance legislation for the former Soviet states was passed in 1992 following heavy lobbying of Congress by the Armenian-American community. Enacted during a period of intensive military conflict in and around Nagorno-Karabakh, its purpose was to prevent U.S. assistance to Azerbaijan. As long as fighting continued and Azerbaijan maintained a blockade of Armenia, the only aid the U.S. government could provide was humanitarian aid for displaced persons and to non-government organizations.

Azerbaijanis—from President Aliyev down to the poorest IDPs living in rail cars near the line of contact—told me that FSA 907 was unfair and biased toward Armenia. Not being able to provide U.S. aid under these circumstances made Azerbaijan less interested in advancing U.S. energy priorities or responding positively to our entreaties about democracy, human rights, and press freedom.

Where Do We Go From Here?

U.S. leadership across successive administrations has been critical to the success Azerbaijan has enjoyed. Our support for the international consortium and Azerbaijan’s development of its resources has blunted efforts by Moscow and Tehran to undermine the independence and sovereignty of Azerbaijan. These efforts continue today, but Baku is in a stronger position to resist them thanks to U.S. support.

At the same time, the global energy environment is unrecognizable from that of September 1994. The production, pipelines, and positioning that drove U.S. energy geopolitics in the 1990s do not apply today. Rather than worry about where the next barrel of imported oil will come from (notwithstanding the recent attacks on Saudi oil facilities), today’s challenge is to find markets for U.S. exports of oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG). Azerbaijan has shifted from being an essential energy partner to being a competitor to U.S. energy exports.Azerbaijan has shifted from being an essential energy partner to being a competitor to U.S. energy exports. It is time for both Washington and Baku to adjust to the new reality.

In particular, Washington should develop a new Azerbaijan strategy based on:

Restrained U.S. energy diplomacy. Globally, Azerbaijan’s energy influence is less than it was in the 20th century. The last two major U.S. oil companies—ExxonMobil and Chevron—have pulled out of production in Azerbaijan. The major pipeline routes to Europe—Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan for oil and the Southern Gas Corridor for gas—are mainly in place already. A Trans-Caspian Pipeline for Turkmen gas is of little interest to the United States, as Washington seeks the same European markets for U.S. LNG.

Modest U.S. regional security interests. As the Trump Administration winds down its military presence in Afghanistan, the importance of the Northern Distribution Network as a determining factor in U.S. security interests in Azerbaijan will diminish. Azerbaijan’s long-standing commitment to ISAF will wane as well.

More careful engagement regarding Iran. Azerbaijan’s effort to balance its strong security relationship with Israel and its "strategic” relations with the United States and Russia put Baku in a vulnerable position. U.S. and Israeli demands for Azerbaijan’s support of sanctions and military actions regarding Iran will only increase that vulnerability. Tehran and Moscow know this. Strong U.S. rhetoric supporting Azerbaijan will not provide the security Azerbaijan needs in the event of a U.S.-Israel-Iran military conflict. Enhanced U.S. security assistance will only unnecessarily antagonize Iran and Russia without increasing Azerbaijan capabilities to resist either.

Normal relations before strategic relations. The Contract of the Century, the subsequent pipeline development, and the continual U.S. military presence in Afghanistan created conditions that encouraged Baku to believe Washington "needed” it as a strategic partner. This sense of control and leverage led Baku to expand human rights abuses and slow democratic and economic reforms. The unbridled corruption among the ruling elites has contributed to these trends. It is time for a step back from talking about a strategic partnership to developing a healthy relationship: one based on shared values of observing human rights, especially freedom of expression; and implementation of Azerbaijani rhetoric on democratic development and economic reform. If there is progress in these areas, then the Administration should consider seeking repeal of FSA 907. It would be difficult under current conditions between the Trump Administration and Congress, but worth a try. Doing so now, however, became more difficult in light of the September 27 letter from

Representatives Pallone, Speier and Schiff asking for a halt in military aid to Azerbaijan and a reassessment of the Section 907 waiver that permitted such limited U.S. military assistance. Absent such progress, then the Administration should consider applying Global Magnitsky sanctions.

Intensified diplomatic engagement with Azerbaijan and Armenia regarding Nagorno-Karabakh. The risk of armed conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan is higher than it was before the four-day war in April 2016. The U.S. government never pressed for a settlement before the energy income flows encouraged Azerbaijan to believe it could buy the military superiority to defeat Armenia on the battlefield. Negotiating a peaceful resolution to this conflict remains, along with supporting Georgia, the most critical priority for U.S. foreign policy in the region.

Ambassador (ret.) Richard D. Kauzlarich is distinguished visiting professor at the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University and former U.S. Ambassador to Azerbaijan (1994-1997).

www.anews.az

Similar news

Similar news

Political News

18:48

Azerbaijani President: By burning our flag, Armenians only showed their ugly qualities to the whole world

Political News

10:30

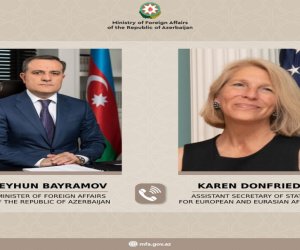

Azerbaijani FM, US Assistant Secretary of State discuss peace process between Azerbaijan and Armenia

Photo

Photo

Video

Video