Paparazzi! How an unloved profession has shaped us

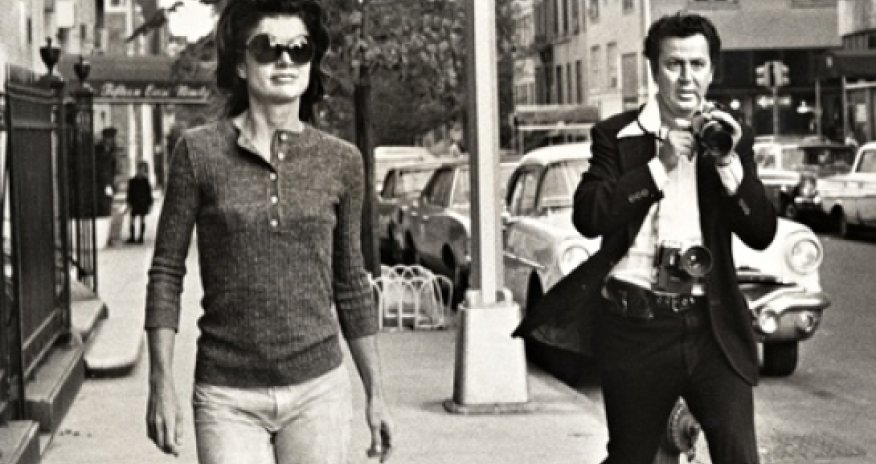

The "stolen" nature of these images – and the associated implication of a predatory force capturing something the subject wishes to keep closely guarded – is explored in a major new exhibition at the Pompidou Centre in Metz in the north-east of France. Paparazzi! Photographers, Stars and Artists seeks to examine the modus operandi of some of the most successful paparazzi photographers of the last 50 years and to unpick the complex reciprocal ties that bind together photographer and subject.The exhibition, which opened last week, features the work of the world's leading paparazzi, whose subjects range from Jackie Onassis to Paris Hilton, and also traces the influence of the genre's aesthetic on artists such as Andy Warhol and Cindy Sherman."We don't take a position on the rights or wrongs of paparazzi photographs," explains the curator, Clément Chéroux. "What we try to do is to take a step back and to look at the subject scientifically. The phenomenon exists and its existence says a lot about our rapport with the media, celebrity, rumour, gossip, as well as our relationship with the news."In our increasingly visual, 24-hour news culture, paparazzi photographs have become a shorthand for revelation. Even in France, where privacy laws are tight, the "stolen image" is these days almost par for the course.Last month, the French edition of Closer magazine published images which purported to show the president, François Hollande, conducting an affair with actress Julie Gayet. Two weeks later, Hollande broke off his longstanding relationship with France's unofficial "first lady", Valérie Trierweiler. The photographer in question was Sébastian Valiela, one of the world's leading paparazzi, who, 20 years earlier, had revealed the existence of former French president François Mitterrand's "secret" daughter Mazarine with a single grainy picture of the two of them leaving a restaurant.In 2012, the same magazine had caused an international furore by printing photographs of the Duchess of Cambridge topless on holiday in the south of France. "The paparazzi make history as well as witness it," explains Chéroux. "There are certain events that have become important because they have been photographed."Getting the shot frequently requires ingenuity and subterfuge. One section of the exhibition investigates the lengths to which paparazzi will go in order to land their prey. A series of photographs by the artist Christophe Beauregard entitled Hush… hush shows paparazzi in various states of disguise – including a man in full camouflage, hiding in the undergrowth of the Bois de Boulogne.The image is almost military. And, according to Chéroux, the myth of the paparazzo has historically been cast in opposition to the myth of the war photographer: "In the public consciousness, the paparazzo is seen as a loser, someone who is not very normal, who will sell his grandmother for money. He has no ethics, he's a bit dirty. He is the antihero, whereas the war photographer is the hero: a figure who risks his life to bring back images from the front. In reality, things are a lot more complex."The snatched photograph has a long, if not necessarily noble, history. As early as 1898, two photographers bribed a member of Otto von Bismarck's staff to let them photograph the iron chancellor lying sunken-cheeked in his bed a few hours after his death.Sixty-two years later, the name paparazzo was given to the fictional news photographer in Frederico Fellini's his 1960 film La Dolce Vita. The term was a contraction of pappataci (mosquito) and ragazzi (boys or guys) and embodied, for Fellini, the irritating invasiveness of the scandal-sheet photographers who prowled the streets of 1950s Rome in search of celebrities and socialites to snap.In a case of art imitating life, the film's star, Anita Ekberg, was hounded by real paparazzi for years afterwards. By 1980, Ekberg was tiring of their antics – one of the exhibition's most striking photographs depicts Ekberg flashing a light towards paparazzo Marcello Geppetti, effectively obscuring his view of her.For Chéroux, the picture of Ekberg represents both the gendered nature of the paparazzi gaze – the vast majority of the photographers are men, often hunting down lone women – as well as the nascent tendency for stars to rebel against the intrusion of the lens.Modern celebrities including Sandra Bullock, Kylie Minogue and Joseph Gordon-Levitt have taken to turning the camera back on the paparazzi who trail them. Others, including Sean Penn and Miley Cyrus, have physically lashed out. But, says Chéroux, the relationship between paparazzo and star is a symbiotic one. They both get something out of it – the photographer by selling his work, the star by remaining in the public eye.Celebrities have often used the paparazzi to manipulate their own image. Chéroux cites the example of actress Sophia Loren who, following the birth of her son Carlo in 1968, was being harassed by photographers for the first picture of her baby. Loren arranged with the Italian paparazzo Tazio Secchiaroli to be at a certain park at a certain time, where he took supposedly spontaneous pictures of the two of them playing."After that," says Chéroux, "the pursuit was finished… Some paparazzo photographs have a certain truth due to the spontaneity of their work… there is an authenticity there. But from the moment the paparazzi photograph became recognised as an aesthetic form, it became easy to fake. So certain celebrities begin to stage shots because they need to pass information on to their public – either they want to relaunch their career or they need money."Such tangled motivations lead to toxic outcomes. The late Princess Diana – one of the "icons" examined in the exhibition – is believed to have tipped off press photographers as to her whereabouts. After she died in a car crash in 1997, the paparazzi who chased the speeding Mercedes through the streets of Paris were found partly responsible for her death.It is difficult, in those circumstances, to believe that the work of the paparazzi should be celebrated. In the three years that it has taken to put together the exhibition, has Chéroux developed a grudging respect for the people who purvey these images volées? "Behind each camera there is a human being," he says after a slight hesitation. "Sometimes they are very nice. And sometimes they are awful. But the phenomenon exists because there is the demand for it from the press – and from the readers."(theguardian.com)ANN.Az

Photo

Photo

Video

Video