The last dragoman: Azerbaijan’s Vafa Guluzade

By Joseph Hammond

In the 21st century, linguistic abilities are increasingly seen as unnecessary for diplomatic success. A diplomat who is bilingual is considered gifted. Vafa Guluzade, a former national security adviser for Azerbaijan who worked with three of that country’s first presidents, died on May 1st 2015. He was a former Soviet diplomat and member of Azerbaijan’s Communist Party, who spoke five languages.

Born in 1940 to an Azeri family that had suffered during the Bolshevik consolidation of his country, Guluzade’s life would be significantly influenced by his diplomatic involvement in two conflicts: the 1973 October War and the Azeri-Azerbaijan War, which took place between 1988 and 1994.

As a student in the Soviet Union, he was obliged to undertake intermittent agricultural work during school holidays. It was on one of these trips that he forged a lifelong friendship with Abulfaz Elchibey. In the work camps, the two would discretely discuss the failings of the Soviet regime. When Elchibey became the second president of Azerbaijan in June 1992, he asked Vafa Guluzade to be his national security advisor, a post Guluzade had also held under Ayaz Mutallibov, Azerbaijan’s first president.

President Clinton

Throughout his career, Guluzade’s gift for languages proved to be key to his success. His linguistic skills recall the dragomans, the professional translators of the Ottoman Empire, often Greek in origin who spoke Turkish, Arabic, Persian and at least one European language. Guluzade could have easily achieved this qualification. In addition to his native Azeri Turkish, Guluzade spoke fluent Russian, Arabic, English, decent Persian and had a passive knowledge of French and German. On one occasion, while translating for Azeri President Heydar Aliyev in America, he paused to grammatically correct Bill Clinton’s translator, who was a Russian emigre.

Nor was that Guluzade’s only memorable encounter with President Clinton. While working for Aliyev one morning in the Azeri government foreign ministry, he was roused from his desk by a secretary. An English speaker had rung, could Guluzade take the call? As a favor to the secretary, Guluzade picked up and was surprised to find the speaker represented American president Bill Clinton. The president wanted to speak with the Azeri president, Heydar Aliyev, regarding an urgent matter. Guluzade unflinchingly took the call on behalf of his small Azeri government and told the speaker that he would arrange the meeting and to call back in thirty minutes.

Around thirty minutes later, he was sat uncomfortably in the president’s office, waiting for the phone to ring. An awkwardly rigged jury system would allow him to translate between Clinton and Aliyev. When the phone rang, Clinton quickly got to the point. According to Guluzade’s recollections, Clinton asked Aliyev if he would be interested in "diversifying” Azerbaijan’s hydrocarbon exports. Any good translator does more than just translate and Guluzade put down the phone and explained to Aliyev that this would mean moving away from Russia and opening Azerbaijan to foreign oil and gas exploration. Aliyev agreed with Guluzade and told Clinton he was interested. The president ended the call by promising that American officials would shortly be in touch. From that phone call, the seeds of the 1,768 kilometres long Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline were planted. The BTC pipeline became operational in 2005.

The call also demonstrated that in the early 1990s, the post-Soviet Caucasus lacked stability. Chechnya momentarily broke away from Russia. Georgia had to contend with independence movements in Adjara, Abkhazia and South Ossetia. It was in this context that the Russian Federation first flexed its political power, supporting Armenia in the Armenia-Azerbaijan War. When the West and NATO failed to react, it lead to other open-ended Russian adventures in Central Asia, the Balkans, Moldova, Georgia, Estonia and most recently Ukraine. Guluzade later said that he earned the trust of President Aliyev by never asking for personal favours when the two met. Often, they spoke either in person or over the phone up to 6 times a day.

October Surprise

Vafa Guluzade graduated in 1968 from the Institute of Middle Eastern Studies at the USSR Academy of Sciences in Moscow with a degree in Egyptian Literature. His early emphasis on learning critical languages was not surprising. In fact, Soviet diplomats often started their careers as interpreters, which is markedly different from the system found in most other countries.

Guluzade’s language skills proved superior to those of Abulfaz Elchibey who, although he had similar interests, was assigned to work on the Soviet project to build the Aswan Dam while Guluzade got a prestigious assignment in Cairo. The young diplomat soon fell in love with the city. He purchased his first car there and enjoyed the nightlife, which was far more liberal than that on offer in the Soviet Union. In addition to Azeri leaders and Bill Clinton, Guluzade also went on to translate for other world leaders including Anwar Sadat, Hafez Assad and Leonid Brezhnev.

It was in Cairo that Guluzade first attracted the attention of Heydar Aliyev. Aliyev arrived in 1973 as the head of a senior Soviet delegation. The interpreter Aliyev brought from Moscow had been a philosophy major and had only studied classical Arabic. He lacked the necessary knowledge of Egyptian colloquial Arabic and appropriate political terminology. Guluzade was drafted in as a last minute replacement. While others may have been hesitant about such a high-profile role, Guluzade saw it as an opportunity. Aliyev praised his translation abilities and left Guluzade gifts when he departed. The October 1973 war nearly led to a confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States. As the conflict progressed, Guluzade quickly rose to become the senior Soviet translator in Egypt. Aliyev would later promote Guluzade to a bureaucratic post in Azerbaijan following his return from Egypt.

Guluzade last visited Egypt in the 1990s, where he bemoaned the loss of the old Cairo he had known in the 1970s. The neighborhoods of Dokki and Mohandiseen, where he had lived as a young diplomat amongst villas and low slung homes, now boasted block after block of soulless, tightly packed apartment buildings.

Inheritors of Empire

Although Guluzade took a friendly view of the United States and Turkey, he saw Russia and Iran as empires in the traditional sense of the word. In a 2011 interview, he said of Russia "it is not a federation, it is an empire.” Both countries although officially republics, had inherited the borders of former empires and were home to millions of citizens who might have prefered to have their own states. He believed that because of their imperial structures and borders, eventually, the Russian Federation and the Islamic Republic would collapse. The reunification of Azerbaijan with South Azerbaijan was, he believed, ultimately inevitable.

Having lead fruitless negotiations with Armenia to end the occupation of Nargano Karbakh., Guluzade came to believe that the ultimate authority in Yerevan lay with Moscow. In later years, he would joke that whilst the war had left 20 percent of Azerbaijan occupied by Armenia, it left 100 percent of Yerevan occupied by Russia and limited the freedom of Armenia’s foreign policy. He firmly believed in a fully autonomous Nargarno-Karbakh and had hoped at one point to offer Armenia involvement in the BTC project in exchange for an end to its occupation. Armenia benefiting from Caspian hydrocarbons might entice it to join the Europeanisation project.

Guluzade’s foregin policy views were broadly realist but, when in full flow, he could make even the most seasoned of cold warriors blush. He favoured close relations between Azerbaijan and both Israel and Turkey. In 1999, he went too far and was forced from power after he advocated that Azerbaijan join NATO, or at least host a US base.

After his dismissal from power in 1999, he would sometimes slip into hyperbole. He claimed that the seizure of Nargarno-Karbakh had been more brutal than Operation Barbarossa because the Armenians destroyed homes. Like George Orwell, he saw Stalin as a greater threat than Hitler in the 20th century.

His death leaves Baku bereft of one of its greatest foreign policy thinkers and a man of peace who worried toward the end of his life that the next generation of Azeri leaders would be able to end the Armenian occupation of Azerbaijan in a peaceful manner. However,, some of his final comments were less pessimistic. Last year, he noted in an interview that the conflict between Russia and Ukraine had made a pro-American regime in Baku more valuable to Washington. Crisis, as he had first learned in Cairo in 1973, could also bring opportunity.

NOTE: Joseph Hammond is a former correspondent for Radio Free Europe and a freelance writer. He has written for The Economist and the International Business Times, amongst other publications.

(New Eastern Europe)

www.ann.az

Similar news

Similar news

Political News

18:48

Azerbaijani President: By burning our flag, Armenians only showed their ugly qualities to the whole world

Political News

10:30

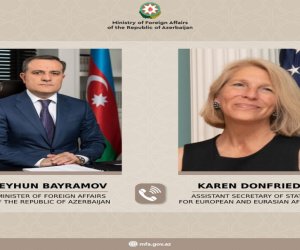

Azerbaijani FM, US Assistant Secretary of State discuss peace process between Azerbaijan and Armenia

Photo

Photo

Video

Video