Think again: prostitution - PHOTO

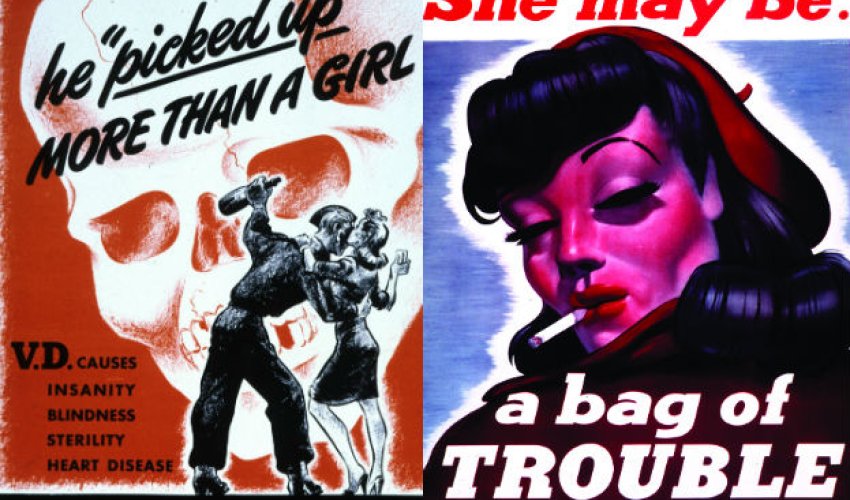

BY AZIZA AHMED"Prostitution Is Bad."Prostitution may be the world's oldest profession, but there is still little agreement on the social and moral legitimacy of commercial sex. There are, of course, those who consider sex sacred and its sale a sin, and there are libertarians who are willing to accept nearly any degree of sexual freedom. But plenty of people have views that lie somewhere in between, and they are fighting over the fairness, regulation, and even the precise definition of what advocates and practitioners increasingly refer to as "sex work."Take France, for instance, where a debate erupted last fall over a proposed law that would fine people $2,000 for purchasing sex. All sorts of protesters took to the streets: women arguing that the law was necessary because violence and coercion are endemic to the sex industry, and sex workers, hoisting posters with slogans like "La repression n'est pas la prevention," who condemned the law. A group of men also insisted in a letter that the government take its hands "off our whores." Ultimately, on Dec. 4, the lower house of Parliament adopted the measure.The French case is but one example of a global dispute about what constitutes exploitation in the sale and purchase of sex -- and it also shows that one side of the argument often has the upper hand. That side, a group of odd bedfellows frequently called abolitionists, thinks that because all prostitution is inherently degrading and dangerous, it must be eliminated. The group draws from, among others, religious and faith-based organizations, both liberal and conservative political ranks, and some outspoken feminist camps. (The driving force behind the controversial measure in France is Women's Rights Minister Najat Vallaud-Belkacem.)So strong is the influence of this group that it has shaped the language typically used to describe the global sex industry. In common parlance, sex work is a dangerous phenomenon that routinely violates women's rights and perpetuates their subordination to men. There is hardly a distinction drawn between sex work and human trafficking, which involves controlling someone through threats or violence with the express purpose of exploitation. This conflation leaves no room for sex workers who make decisions for themselves; they are all just victims. "The term 'sex worker' is false advertising," says the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women.This is more than a semantic issue. Since George W. Bush's administration, the U.S. government has required that international organizations receiving funding for efforts to combat trafficking and HIV/AIDS must not "promote, support, or advocate the legalization or practice of prostitution." In an October 2013 call for project proposals, the State Department reiterated, "The U.S. Government is opposed to prostitution and related activities, which are inherently harmful and dehumanizing, and contribute to the phenomenon of trafficking in persons."This stance has put sex workers and their advocates -- who support the idea that some people choose, although perhaps from a range of poor economic options, to sell sex -- in an impossible position: They must make a choice between compromising their principles or missing out on opportunities for much-needed money. Such was the case with SANGRAM, a sex workers' collective in India that refused to adopt an anti-prostitution pledge required by the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR. (The U.S. Supreme Court struck down the pledge as a violation of free speech in June 2013, but this was only a partial victory: Foreign, as opposed to U.S.-based, NGOs could still be barred from receiving funds, and the court did not address PEPFAR's ban on advocating the legalization of prostitution.)To make matters worse, the influence of prostitution's vocal opponents has contributed to a dearth of good data on the global sex industry, including its most harmful aspects. In July 2006, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) acknowledged that U.S.-cited statistics of people trafficked around the world are questionable. The GAO highlighted a figure, cited by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), that there are 80,000 to 100,000 trafficked women and children in Cambodia. But that number came, originally, from a publication by Cambodia's Ministry of Planning that discusses the total number of sex workers in the country; there is no breakdown of who is an adult or who is a victim of trafficking.To better understand and address enormous wrongs like trafficking, we need good data. But that first requires grasping the dangers of targeting sex work -- which involves women, men, and transgender populations -- writ large for elimination. Abolitionists say they want to protect human rights, but their efforts often undermine those rights: Campaigns and programs to end prostitution in fact lead to violence, stigmatization, and other problems for the exact people they claim to be helping. "We Can Abolish Prostitution by Making It Illegal."NO.Laws regulating sex work vary widely among countries. It's illegal to buy and sell sex in the United States (with some exceptions). Germany legalized prostitution in 2002, and in December 2013, Canada's Supreme Court struck down the country's anti-prostitution measures. Thailand, meanwhile, has long outlawed sex work, yet the industry operates quite openly there.Abolitionists typically insist that criminalization is imperative. Some have pushed for making the sale of sex illegal. Others, however, including feminists who oppose prostitution, support a different model: outlawing only the purchase of sex. They argue that criminalizing clients will force the sex industry out of business, liberating sex workers but not treating them as criminals.Already, this model has achieved legislative success. Sweden outlawed buying sex in 1999; Norway and Iceland later followed suit. France is on the verge of joining the club, and a debate on the issue is even gaining steam in Germany. Feminist Kathleen Barry, author of Female Sexual Slavery and co-founder of the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women, has even called for an international treaty that would mandate "arresting, jailing and fining johns." (She first introduced the idea in the early 1990s, but has recently revived it.)In reality, there is no convincing evidence that punishing "johns" decreases the incidence of commercial sex. Troublingly, Sweden's sex workers report that criminalization has simply driven the sex industry underground, with dangerous consequences: Clients have more power to say when and where they want to have sex, inhibiting workers' ability to protect themselves if need be.Evidence shows, too, that criminalization of sale or purchase (or both) makes sex workers -- many of whom come from marginalized social groups like women, minorities, and the poor -- more vulnerable to violence and discrimination committed by law enforcement. Criminalization can also dissuade sex workers from seeking help from authorities if they are raped, trafficked, or otherwise abused. These problems have been identified in many countries: A 2012 report by the Open Society Foundations documented sex workers being harassed, extorted, and intimidated by police in the United States, Russia, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Namibia, and Kenya. And in Sweden, sex workers have reported that they are still targeted by police, including for invasive searches and questioning.Sex workers, their advocates, institutions like the Global Commission on HIV and the Law, and a growing number of experts in health and law argue for removing all criminal prohibitions for consenting adults. After all, sex will be bought and sold no matter a country's laws. The question, then, isn't how to get rid of sex work -- it's how to make it safe for those who do it. Decriminalization would allow sex workers access to government and international resources so they could better respond to threats like violence and trafficking, while also helping to ameliorate the social stigma and prejudice they so often face."We Should Rescue Prostitutes From Brothels."NOT NECESSARILY.On top of arguing for criminalization, some abolitionists agitate for actively removing people from the sex industry -- that is, entering brothels in "raids," pulling sex workers out, and placing them in rehabilitation programs. Proponents of rescues, whose views dominate many anti-trafficking organizations, have secured substantial international funding. The U.S. government, for example, has given grants to organizations like the International Justice Mission (IJM), a faith-based group headquartered in Washington, D.C., and the Anti-Trafficking Coordination Unit Northern Thailand, both of which actively promote rescues.But rescues are often far from heroic. IJM has been criticized for failing to distinguish between sex workers and trafficking victims. Describing the response among people pulled from a Thai brothel in a 2003 IJM raid, a sex worker advocate told the Nation, "They were so startled, and said,'We don't need rescue. How can this be a rescue when we feel like we've been arrested?'" More recently in Thailand, law enforcement has scrambled to respond to U.S. criticisms of the country's anti-trafficking record by stepping up raids. "[In 2012], the Royal Thai Police ordered all police units to spend at least 10 days each month doing anti-trafficking work," Gen. Chavalit Sawaengpuech told Public Radio International (PRI) this past October. In effect, PRI noted, the police are "trying to meet a quota … even where there isn't data or evidence indicating the sex workers they are rescuing are victims after all."Violence perpetrated by local authorities during raids has also been documented from South Asia to Africa to Eastern Europe. In 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO) wrote in a bulletin that "research from Indonesia and India has indicated that sex workers who are rounded up during police raids are beaten" and "coerced into having sex by corrupt police officials in exchange for their release." The bulletin added, "The raids also drive sex workers onto the streets, where they are more vulnerable to violence." So rampant have these problems with police become in Cambodia that, in June 2008*, more than 500 sex workers rallied in Phnom Penh, chanting, "Save us from saviors."Also troubling are some of the rehabilitation centers -- run by NGOs, churches, or governments -- where "rescued" sex workers are placed. These centers profess to offer medical care, counseling, and vocational training. Yet many are known for perpetrating violence, detaining individuals, and separating them from their families. The WHO bulletin stated that some Indian and Indonesian sex workers are "placed in institutions where they are sexually exploited or physically abused." In Cambodia, Human Rights Watch (HRW) has documented beatings, extortions, and rape at government rehabilitation sites. And in the state of Maharashtra, India, in addition to holding women for long periods of time, a rehabilitation home has suggested that marrying them off is a mode of rehabilitation.The rescue approach certainly makes for good optics. It has been covered, notably, by Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times, who live-tweeted a brothel raid in 2011. And the impulse to protect is surely a noble one. But in addition to ignoring that some people choose to sell sex, rescues have subjected sex workers to a whole host of abuses -- a fact certainly problematic for the abolitionists who champion such interventions in the name of human rights."But Kristof Writes About Child Sex Slaves -- and We Have to Save Them."OF COURSE, BUT HOLD ON.During the brothel raid Kristof covered in 2011, which took place in Cambodia, the columnist tweeted, "Girls are rescued, but still very scared. Youngest looks about 13, trafficked from Vietnam." His discovery highlighted an abhorrent reality that concerns both advocates and opponents of sex work: Many in the sex industry endure forced migration, torture, captivity, and other wrongs. Some of these people are adults, but others are young girls and boys. We should do all that we can to end these horrors, and no child should be involved in the sex industry.To that end, international laws and standards explicitly condemn child prostitution, including a protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child and another to the Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime. UNICEF has expressed a "zero tolerance" policy on the issue. The United States, meanwhile, has taken its own legal stand with the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (reauthorized in early 2013), and many countries have their own anti-trafficking legislation.Yet, ironically, current efforts to end the sexual exploitation of children often endanger them. In many countries, authorities victimize trafficked children the same way they do adult sex workers. Raids to save children are engulfed in the same sort of challenges as the ones seeking to "liberate" adults; HRW's report on Cambodia found that children pulled from the sex industry were forced to pay bribes to the police and faced mistreatment at a government rehabilitation center. Moreover, governments frequently adopt "blanket solutions" to address trafficking, failing to acknowledge that each child's circumstances are different. "While policies are evidently needed which can be applied to all children," Mike Dottridge, former director of Anti-Slavery International, has written, "if they do not take account of the huge variations which occur in reality, they are likely to harm children."These problems don't just exist outside the United States. Children in the U.S. sex industry are often arrested and put into the juvenile detention system "instead of in environments where they can receive needed social and protective services," noted a 2011 Congressional Research Service report. A September 2013 report by the Institute of Medicine and National Research Council also found that, as of early 2012, only nine states had enacted laws ensuring that minors accused of prostitution are exempted from prosecution.Currently, then, many efforts to save children from the sex industry are neither safe nor fair to them. Correcting that poor record will mean improving laws that target human trafficking, dedicating more resources to quality interventions, addressing the social and economic conditions that make minors vulnerable to exploitation, and making sure their voices are heard. It also means respecting and engaging adult sex workers and their advocates as part of the solution, not the problem. After all, sex workers are often the first to notice those being coerced into selling sex -- including children -- or they are the first individuals whom trafficking victims reach out to for help."Prostitution Spreads Disease."WRONG WAY TO LOOK AT IT.Sex workers have long carried the stigma of being vectors of infection. In the 1940s, U.S. government posters discouraged soldiers from purchasing sex with slogans like "SHE MAY LOOK CLEAN -- BUT" and "DISEASE IS DISGUISED." Throughout the HIV epidemic, governments have targeted sex workers for spreading the deadly virus. Crackdowns on places and people who sell sex have been routine, carried out under the auspices of protecting public health. Recently, in countries like Greece and Malawi, authorities have arrested sex workers and forced them to undergo mandatory HIV testing, a clear violation of health and privacy rights.To be sure, there are public health concerns surrounding sex work, including high rates of sexually transmitted infections. But punishment and humiliation cannot possibly be the answer. Similarly, criminalization only impedes access to medical care. In 2012, the WHO stated, "Laws that directly or indirectly criminalize or penalize sex workers, their clients and third parties … can undermine the effectiveness of HIV and sexual health programmes."What's more, in the United States, police in several major cities harass or arrest sex workers carrying multiple condoms, citing them as evidence of illegal activity. In response, some sex workers have told reporters, activists, and others that, fearing police, they sometimes do not carry condoms -- and thus end up having sex without them.What we should be doing instead is focusing on protecting, not persecuting, sex workers. Grouped under the banner of "harm reduction" -- and supported by the WHO and UNAIDS -- are programs that distribute condoms, educate sex workers about HIV and other health risks, and provide them checkups, medicine, and counseling. These programs are sometimes run by sex workers themselves. In India, SANGRAM monitors condom use, cares for sex workers with HIV, and even works to bar violent customers from brothels. Anti-trafficking initiatives can also be built into peer-to-peer programs of harm reduction, as SANGRAM has done. "Sex worker rights groups should be involved in the genuine anti-trafficking work because, at the end of the day, they know their industry and their spaces and they're better at it," SANGRAM's Meena Saraswathi Seshu told the U.N. news agency IRIN in 2013.The results of harm reduction can be dramatic. In the Ivory Coast, a 1990s prevention campaign at "Clinique de Confiance," where women received counseling, clinical exams, and testing for infections, contributed to a decline in HIV prevalence from 89 to 32 percent among participating female sex workers. In southern India, between 1995 and 2008, an increase in health interventions that supplied condoms led to a drop in the prevalence of both HIV and syphilis among sex workers.Yet despite these successes, harm reduction receives insufficient support; according to UNAIDS in 2009, less than 1 percent of global funding for HIV prevention was being spent on HIV and sex work. At least in part, this is due to abolitionists, who have at times disrupted important health initiatives. For example, Durjoy Nari Shangho, a Bangladeshi organization, shuttered drop-in centers for sex workers after the international NGO from which it received funding signed the U.S. anti-prostitution pledge. Similarly, Doctors Without Borders distanced itself from a project on the Cambodia-Vietnam border after U.S. congressional testimony criticized it for promoting sex work.Harm-reduction programs, if more widely accepted, spread out, and scaled up, would go a long way toward protecting sex workers' health. But they shouldn't exist in isolation. They should be coupled with decriminalization and broader legal and social efforts to normalize the sex industry."A Sex Workers' Union?!"THAT'S RIGHT.During demonstrations against France's proposed bill to criminalize the purchase of sex, some protesters carried signs that read "SEXWORK IS WORK." This is true -- and because it's work, it should treated as such. Today, a camp of legal experts contends that the many problems sex workers face can be addressed with labor laws. If sex work were considered a legitimate economic sector, the argument goes, where work conditions, fair wages, injury compensation, and other basic employment issues were matters of law, the sex industry and those within it would be less exposed to violence and other harms. Under a labor model, U.S. sex workers could report health risks at brothels to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. They could unionize and lobby for stronger protections against police harassment. In the long run, they would be viewed as citizens like any other, and their industry as a safe and acceptable one. What's more, law professor Hila Shamir at Tel Aviv University has argued that respecting labor rights in all sectors could help address many of the social and economic forces that lead to trafficking. The same goes for the sex industry: Ensuring safe work environments would decrease exploitation and make it less enticing for sex workers to migrate abroad based on the promise of more money or other benefits.Provocative? Perhaps. But early research already shows that the labor model can work.Already, trade unions of sex workers have launched in the United Kingdom and other European countries, and New Zealand has applied labor protections to the sex industry. Advocacy groups have also begun to use courts to defend their labor rights. In South Africa, an appeals court ruled in 2010 that a sex worker who said she'd been unfairly fired from a massage parlor ("for refusing to perform oral sex, spending time in her room with her boyfriend, choosing her clients and failing to book enough customers," according to the Mail & Guardian) had a right to a hearing before a government body that settles labor disputes. Assisting with the case was the Cape Town-based Sex Workers Education and Advocacy Taskforce.In lieu of formal unions, sex workers' collectives also assert power vis-à-vis brothel owners and police. According to UNAIDS, Service Workers in Group, a collective in Thailand, was able to improve relationships with the police force by introducing an "internship" program, in which police cadets learn about HIV prevention and get to know collective members. This has helped improve police attitudes toward sex work. Moreover, researchers found in a 2009 study that sex workers in collectives in South India have been able to deter arrest and call on one another for assistance when faced with police harassment and other issues.All these examples show the ways in which a labor approach can improve sex workers' lives. Yet moving public favor toward this model won't be easy. Beyond changing minds and diminishing support for abolishing sex work, it will require reallocating resources and amending or throwing out harmful policies. It will also require managing backlash, like the international protest that opponents of prostitution threatened the United Nations with last September, in response to the body's various reports supporting the decriminalization of sex work.As research and experience show, however, change is essential for the rights of sex workers -- the very thing abolitionists claim they wish to protect. Sex workers deserve not only the right to choose how they make a living, but also the right to be free from the fear, mistreatment, and -- at the root of it all -- misconceptions that have long plagued their industry.*Correction: The print version of this article in the January/February 2014 issue incorrectly stated the date of the rally by the more than 500 sex workers in Phnom Penh who chanted "Save us from saviors." The rally was in June 2008, not June 2013. (Return to reading.)(foreignpolicy.com)ANN.Az

Photo

Photo

Video

Video