Truth and propaganda: the other two foes in Gaza's war

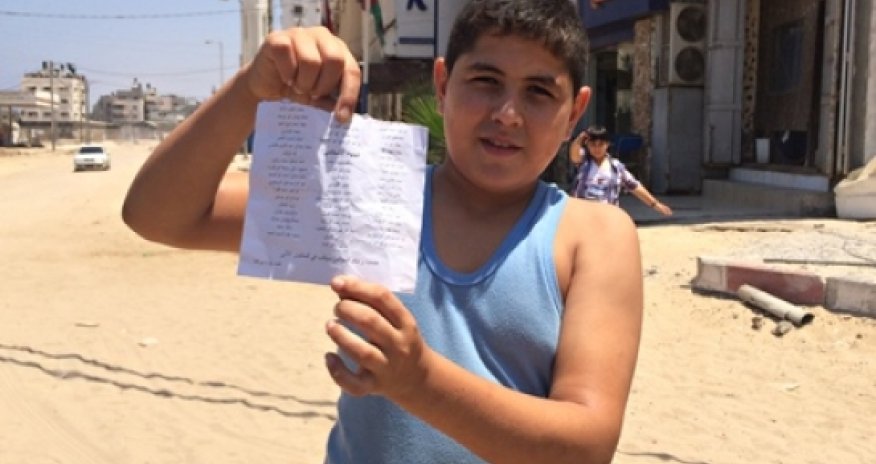

That router enabled me to follow the effect of bombs dropping around me in real time. Locals in Rafah appealing for help, tweeting photographs of the dead in refrigerators. Doctors at Shifa hospital, recounting the night's toll of maimed and burned. Bloggers from Israel disputing everything, convinced the hospital itself is just the lid of a vast tunnel complex for Hamas.My social networks followed me into the war and collided with others – a reminder that warfare has become newly alive with information.The basic suite of tools journalists use has only been around six or seven years – so Gaza is one of the earliest glimpses into how propaganda and truth might intersect in 21st-century warfare.In the morning, information flows through cellphones. Not many ordinary people have smartphones but they do have handsets that double as radios. So you get a real-time, death-by-death account of what's going on over breakfast.Radio, in this situation, comes into its own, but it's not just an information source. As we head towards the fighting, the driver switches from news to the martial music of the Palestinian resistance. Though he is not a Hamas supporter, his intent is to give us the courage to carry on driving.Each night we went to an independent TV production company to feed our video via the satellite dishes on the roof of an 18-storey tower block: here were young Gazan men who'd chosen not to fight, nor to report for a Hamas station, but to do the near impossible: independent agency journalism in a country run by armed paramilitaries.These young journalists lived in a world of information totally connected to the west though Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Their talk was of rival software packages and camera types, and the scholarships to western universities they always just seemed to miss.They'd found ingenious uses for digital cameras. With a sixth sense, they knew when a circling F16 had commenced its bombing run over the pitch-dark city. They would hang a DSLR out of the window on a long exposure to get a night shot of the impact and the smoke cloud – when all the naked eye could see was black. The purpose was not to produce a useable photo, but to get the scoop on what the target was.The propaganda flow in a warzone like Gaza is intense. Its formats range from leaflets dropped by F16s telling people to vacate certain areas to late-night TV speeches by Hamas commanders, through to Twitter and the ultimate social network: word of mouth.But, like all wartime propaganda, it is only effective if it plausibly describes reality. Gazans are materially cut off from the world economy, just as in Cuba: everything patched up and odd flashes of modernity amid an economy trapped in the 1970s – the occasional new car alongside battered Volvos and even more battered donkeys.Gazans I spoke to wanted their sons and daughters to go to university. But, given the choice, they would send them to Kuwait or even Sudan to Islamic universities. Their big fear was that the shock of contact with the west would traumatise them, or make them so different they could never return. In any case – even for the highly talented and educated – the possibility of ever leaving is low.The material effect of being so isolated is that information is reordered around the reality they can't escape: everybody has to care what the Hamas military guy says; his speech is analysed late into the night by groups huddled over cigarettes. Binyamin Netanyahu's speeches are watched for a different reason – every Gazan is an amateur psychiatrist when it comes to Bibi. "Did you see how his eyes kept flicking right and left?" said my Gazan friend. Each facial tic was analysed as potential evidence that Israel was about to crack.Many Gazans I met believed Israel had lost double the number of soldiers its press recorded. They consistently ridiculed the leaflets the Israelis dropped. They consistently claimed that, if Israeli troops tried to enter Gazan urban space, they would be defeated – despite clear evidence that they had already occupied a lot of urban space.All this tells you is that people's desire to believe their own side's propaganda is high, and that's the source of its effectiveness.Social media created an extra public space where a more truthful and nuanced discussion could go on – and it created an outlet for information to the world.During the 10 days I was in Gaza, the most salient information came and went in pictures. Pictures can be doctored, but in general you can tell when one is real if you are there, from who posted it, how quickly it tallies with verbal reports, and so on.The pictures – of bodies, destroyed buildings, injured and anguished people – became the mute forms of communication between people in Gaza and the outside world. Though war photography has always been high-impact, this is one of the first wars where most of it was done by amateurs.If an advanced society ever gets into the kind of war Gaza has been through, I would expect tighter controls on information: strict censorship on what can be tweeted, partial switch-offs of the internet and restrictions on reporters' movements. The absence of these things on the Gazan side made the war reportable through social media.But the conflict showed the limits of social networks when you have two antagonistic societies at war with each other. A memorable network graphic of the war's Twittersphere showed almost no connections between the "blue" internet – of Israelis, the Jewish diaspora and the US Tea party – and the "green", which included the Muslim world and the anti-war movements in the west.In an ideologically divided world, social media's ability to dissolve spin and propaganda becomes relative. The need for truly independent, traditional media does not go away.But the sight of those young Gazan journalists, their sleeping bags piled up on the floor of the edit suites they worked in, was a reminder of how hard it is to remain dedicated to the truth in war.(theguardian.com)Bakudaily.Az

Photo

Photo

Video

Video