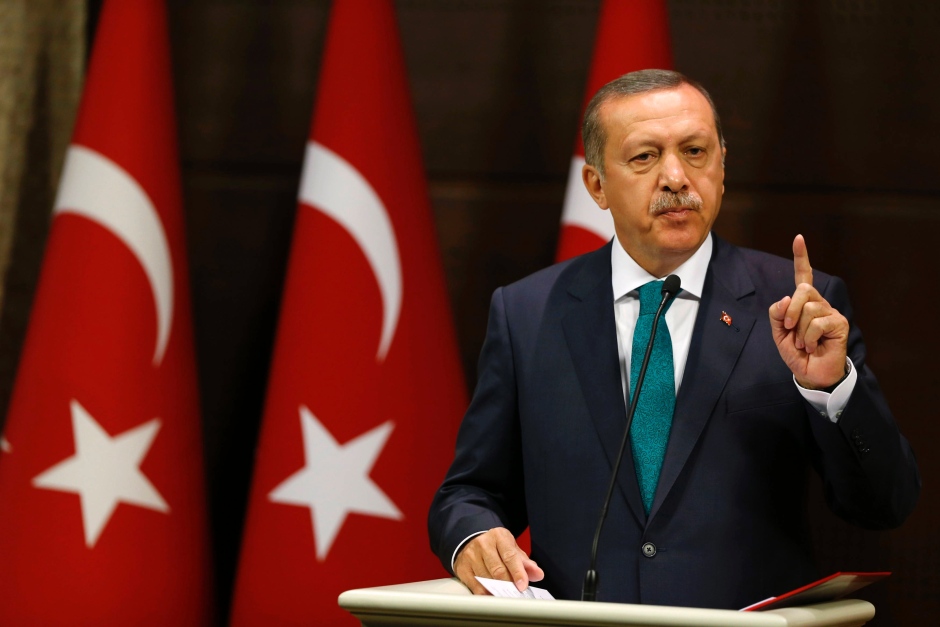

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and the AK Party are back at the reins in Turkey after a landslide election win, and markets were celebrating on Monday. There are enough road-bumps ahead for the $720 billion economy to suggest the euphoria may not last too long.

Investors welcomed the end of a five-month political standoff, and the return of a government with a track record of maintaining growth, taming inflation and luring global business during 13 years in power. Stocks and the lira enjoyed their best day in years.

But the new government takes over in a worse environment than its AK Party predecessors, at home and abroad. Turkey has held four divisive elections in two years, and suffered a wave of violence in recent months. That’s taken a toll on the economy: growth is sputtering, the currency is among the world’s weakest, and consumer confidence is near a six-year low.

There are other challenges that aren’t of Turkey’s making. The last three AK Party governments came to power when the economy was enjoying the global liquidity boom or roaring back from the 2008 crisis. This one will have to engineer a turnaround as emerging markets everywhere nervously wait for the Federal Reserve to start raising interest rates.

As Erdogan and Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu seek to get growth back on track, investors will be looking especially hard at how they address the following issues:

Central Bank Independence

Among the causes of lira weakness are the frequent attacks by Turkish leaders -- Erdogan is probably the worst culprit -- on central bank Governor Erdem Basci, pressing for lower interest rates to bolster growth. The criticism has flowed less freely this year, but it hasn’t dried up completely and some analysts say the AK Party’s electoral landslide could rekindle it.

"We may see renewed pressure on the central bank to ease monetary policy,” Abbas Ameli-Renani, an emerging-market strategist at Amundi in London, wrote in a report Monday.

Restoring the bank’s credibility as an independent policy-maker is essential to keep foreign money flowing into the economy and finance Turkey’s large current-account deficit, according to William Jackson, a London-based emerging-market economist at Capital Economics. If it doesn’t happen, he sees a risk that "the lira may start to fall again.”

There’s also a succession looming at the central bank: Basci’s term is up in April, and some of Erdogan’s economic advisers are reckoned to have less market-friendly views.

Reformers: On the Pitch or On the Bench?

Another personnel question that preoccupies investors is the makeup of the incoming government’s economic team. Earlier this year, there was talk among market types that former Deputy Prime Minister Ali Babacan had fallen out with Erdogan and was destined for exclusion. But the longtime economy czar was unexpectedly invited by Davutoglu to run in the Nov. 1 election.

Babacan and Finance Minister Mehmet Simsek, who’s also back in parliament, are credited by many investors for steering reforms in the AK Party era, and maintaining budget discipline even when growth has been slow -- helping cut the debt burden by more than half since 2002.

Once the post-election relief rally fizzles out, investors will be focusing on whether there’ll be "key places for market bulwarks such as Babacan and Simsek,” Tim Ash, a credit strategist at Nomura International Plc in London, said in an e-mailed note Monday. "If we see Babacan et al take prominent roles, this is good for continuity.”

Worried Business

Business confidence has been slipping, as revealed by the way private investments have stalled since 2011. MIT’s Daron Acemoglu and Murat Ucer, an Istanbul-based economist at Global Source Partners Inc., argue in a paper that the slump reflects damage to Turkey’s civic institutions and judiciary as the AK Party became "too powerful,” undermining confidence in the rule of law.

Companies seen as unfriendly to the AK Party have been hit by tax probes and even government takeovers, and such episodes became more frequent after the nationwide anti-government protests in 2013, which Erdogan partly blamed on business figures he said were seeking to topple him.

Days before the vote, police stormed into the offices of Koza-Ipek Holding, a mining and media conglomeration, and prosecutors installed a new management team. The group was accused of laundering money to fund a religious movement hostile to the AK Party. Shares in Koza companies -- and also Dogan Holding, a media group that’s had a series of run-ins with Erdogan -- plunged on Monday even as the rest of the market was buoyant.

The post-election period will "likely witness further attacks on media outlets and businesses critical of the government,” Naz Masraff, an analyst for the Eurasia Group in London, said in an e-mailed note. "With ongoing obstructions to the rule of law, the business environment will continue to suffer.”

(Bloomberg)

www.ann.az

Follow us !