To return or not: Who should own indigenous art?

Should works included in a new Aboriginal Australian art exhibition be repatriated to the culture that produced them? The answer is complex, writes Jason Farago.

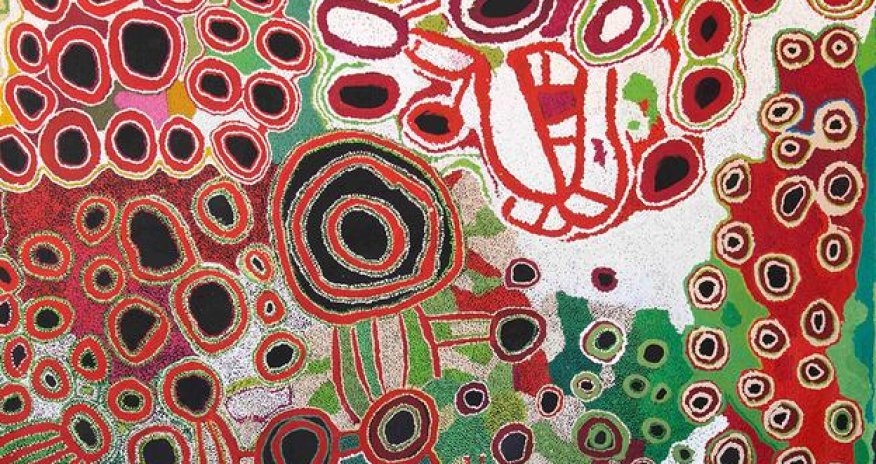

The British Museum in London is opening a major new exhibition with a rather interesting subtitle. Indigenous Australia: Enduring Civilisation the most important show ever in the United Kingdom to look at the art and culture of Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders, and though the exhibition has a massive 60,000-year timescale, it presents indigenous Australian art as part of a continuous culture. Objects from the museum’s collection, such as a shield taken by Captain Cook from Botany Bay – now the site of Sydney’s airport – will be displaye1d alongside bark painting from West Arnhem Land, placards from recent indigenous protest movements and works of contemporary art that reckon with Australia’s past and future.

After the show closes in August, many of the objects on display will travel to the National Museum of Australia in Canberra – and there, debate is already roiling. Numerous indigenous activists are distressed, not to say furious, that artworks and artefacts they consider rightfully theirs will travel to Canberra only to return to London: "just rubbing salt into the wounds,” as one activist had it. What could have been a celebration has quickly become a major front in the endlessly challenging debate over the repatriation of artworks from museum collections to their place of origin. If, as the British Museum subtitle has it, indigenous cultures form an "enduring civilisation,” then are they the proper guardians of their own heritage?‘Who owns culture?’

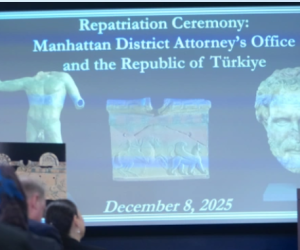

Indigenous claims to objects in Western museums should be understood separately from similar claims on behalf of nation states. The British Museum, of course, knows all about the latter: its prized Elgin Marbles, acquired (or looted?) in the early 19th Century, have been claimed by Greece since 1925. No country has been more forceful in its claims to cultural patrimony in recent years than Turkey, whose culture ministry has laid claims to Byzantine artworks made millennia before the establishment of the Turkish republic, and blocked loans to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Louvre and the Pergamon. Such nationalistic muscle-flexing not only rests on sometimes dubious historical premises, but also on a myopic understanding of culture itself, which has never confined itself to national limits. So to the question ‘Who owns culture?’ we can confidently assert the truth of one response: not the nation state. Cultures do not line up with the boundaries on maps.

But in the case of works of art from indigenous Australia, we are looking at a very different question. Here the petitioners for restitution are not the government of the Commonwealth of Australia, but rather contemporary indigenous communities whose understanding of culture, time and kinship comes into direct conflict with the imperative of the Western museum. This is a much harder, much more fraught debate, raising some of the biggest questions of art and politics: what does it mean to be modern? Does all culture form part of a global heritage that should be available to everyone, even after centuries of war and colonisation? Must everything be presented for universal understanding, or is some knowledge correctly kept secret?

For many indigenous Australians, the objects in the London and Canberra exhibitions are not the material remnants of past lives, but very real connections to their history and their ancestors. They have a point – one that museums have ignored for too long. It remains all too common to see cultural works by indigenous peoples treated as natural history, to be filed away with rocks and bird carcasses, rather than treated as a vital culture in its own right. (When I was a student of art history, I remember the shock of discovering an aboriginal Australian painting in my university’s natural history museum rather than at the art gallery, even though the painting dated from 1988.) As many anthropologists have shown, there is nothing ‘natural’ about the designation of a cultural object as an ‘artefact’ or an ‘artwork’, as living or dead. The distinction is a historically freighted, constantly negotiable dance. In Paris, for example, pre-Columbian sculptures have migrated over and over: from the Louvre and the Musée Guimet in the early-to-mid-19th Century, where they were exhibited as antiquities; to the ethnographic Trocadéro in the late 19th Century, where aesthetics were irrelevant; and now to the Musée du Quai Branly, which proudly calls itself an art museum.

(BBC)

www.ann.az

Similar news

Similar news

Latest news

More news

Photo

Photo

Video

Video